Hey there! Today I am writing about the horrifying and intentionally-impossible-to-understand world of health insurance.

In the USA, being covered by insurance is an essential evil: without it, one catastrophic health event can lead one into financial ruin. Only 40% of Americans have enough saved to cover a $1,000 emergency expense; nearly two thirds of bankruptcies in our country are tied to medical bills. In this world, breaking your arm without insurance (or with, quite frankly) can mean the end of financial stability, loss of home or work, and incredible stress.

Health insurance in the USA is most often tied to employment, with an employer potentially selecting plans for employees and choosing to cover some or all of the monthly premiums that are necessary to even be covered in the first place. For folks who are unemployed or self-employed, they must select a plan through a private insurer or through the health insurance marketplace established by the ACA. These premiums have risen to become exorbitant since their inception, with the average cost for an annual family plan being over $20,000 and the cost for an annual individual plan sitting somewhere around $7100.

This means that for an individual, one either pays or their employer pays as a part of their wages around $7100/year in order to even be covered in the first place, not including a doctor visit or any treatment yet. $7100/year is the price of admission to have insurance even consider to pay something for you. And this number keeps rising, outpacing inflation and wage growth. Insurance often works as a gilded cage to keep folks with employers, and paying their premiums, to stave off woes of going bankrupt due to an unexpected medical issue, which could land them in hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt without coverage.

So although we may disagree with the system (and I fervently do), and want to work to change it, this must happen from the inside out, as we are forced to comply by the rules of the system for the meantime in order to preserve our safety and wellbeing.

Signing up for Insurance through the Marketplace

Because I live and work in Pennsylvania, and because I am a small business owner, I purchase my own insurance through the PA marketplace, Pennie.com, whereas previously I used healthcare.gov to purchase insurance through the ACA. So I will base this portion of the article around this biased experience I have undergone.

Folks can sign up for insurance following a “Qualifying Life Event,” such as loss of a job, turning 26 and getting kicked off parents’ insurance, moving, getting married or divorced, having a kid, citizenship changes, etc.

Signups ask for demographic information like age, location, and tobacco usage. You can then view plans, regardless of signing up, to get an idea of what’s in the budget. And sometimes you’re hard pressed to fit stuff into the budget. I added my info here to see what typical costs are for available plans and as you can see —

It’s a lot. And overwhelming. It’s both good and bad that there are 4 pages of plans, but for the layperson, it’s hard to know which freaking plan will even cover things that you might want or need. And if you click on an individual plan, you’re again inundated with confusing information and a myriad of numbers —

Weighing the pros and cons of which plan to select is hard if you don’t know what it all means, if you don’t know how to afford it, if you don’t know how many visits to the doctor you are going to have in a year, if you are afraid to lock into something for an entire year of your health history and aren’t sure how that coverage is going to work for you. I’ll try and go over some of the basic definitions here, but it doesn’t cover everything one might need to know to navigate finding, buying, and using insurance that is right for their particular case.

Common definitions

So we’ve covered monthly premiums — the amount of money that must be paid to be covered by insurance. This varies by plan, coverage, and location, among other things.

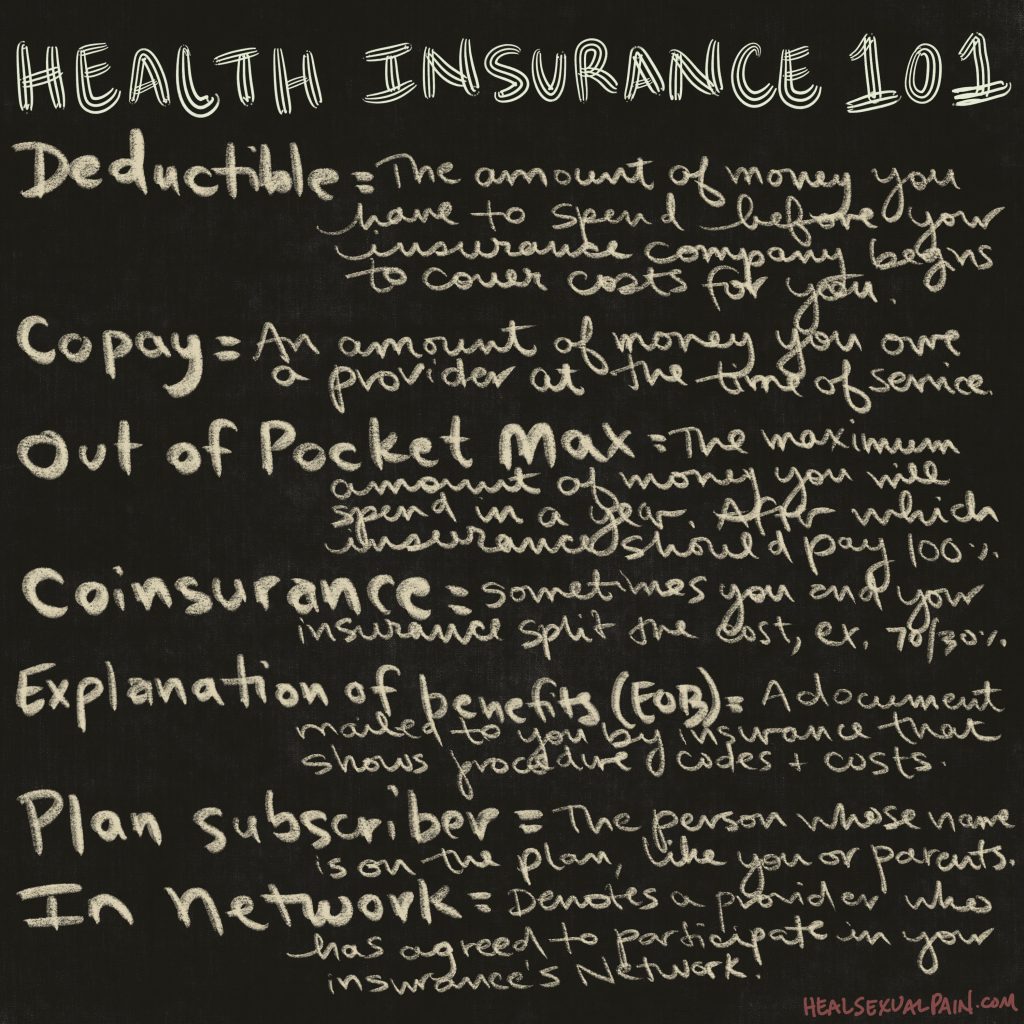

The image above goes into some short definitions in order to demystify —

Deductible – The amount of money you have to spend before your insurance company begins to cover costs for you. This does not apply to the negotiated rates your insurance company works out for your case; those take effect immediately.

Copay – An amount of money you owe a provider at the time of service.

Out of pocket max – The maximum amount of money you will spend in a year, per your insurance company. After meeting this amount, your insurance company covers expenses 100%.

Coinsurance – Sometimes you and your insurance split costs, for example they pay 70% and you pay 30%.

Explanation of Benefits – A document mailed to you by insurance that shows procedure codes and costs. It also shows dates of care and where that care took place and with whom, generally. An EOB is NOT a bill. But you can use it to cross-reference if you get a bill directly from a provider.

Plan Subscriber – The person whose name is on the insurance plan, generally you, or your parents (if under age 26). This is important because if you seek care on someone else’s plan, you may need the subscriber’s info like name and date of birth.

In-Network – Denotes a provider who has agreed to participate in your insurance’s network. More said on this later.

Out-of-Network – Denotes a provider who has not agreed to participate in your insurance’s network. More said on this later.

Claim – This refers to a time you saw a medical professional for some reason, whether a visit or procedure, and they report that information to your insurance (if in-network), or send you a bill directly (if out-of-network). Generally.

Reading Your Insurance Card

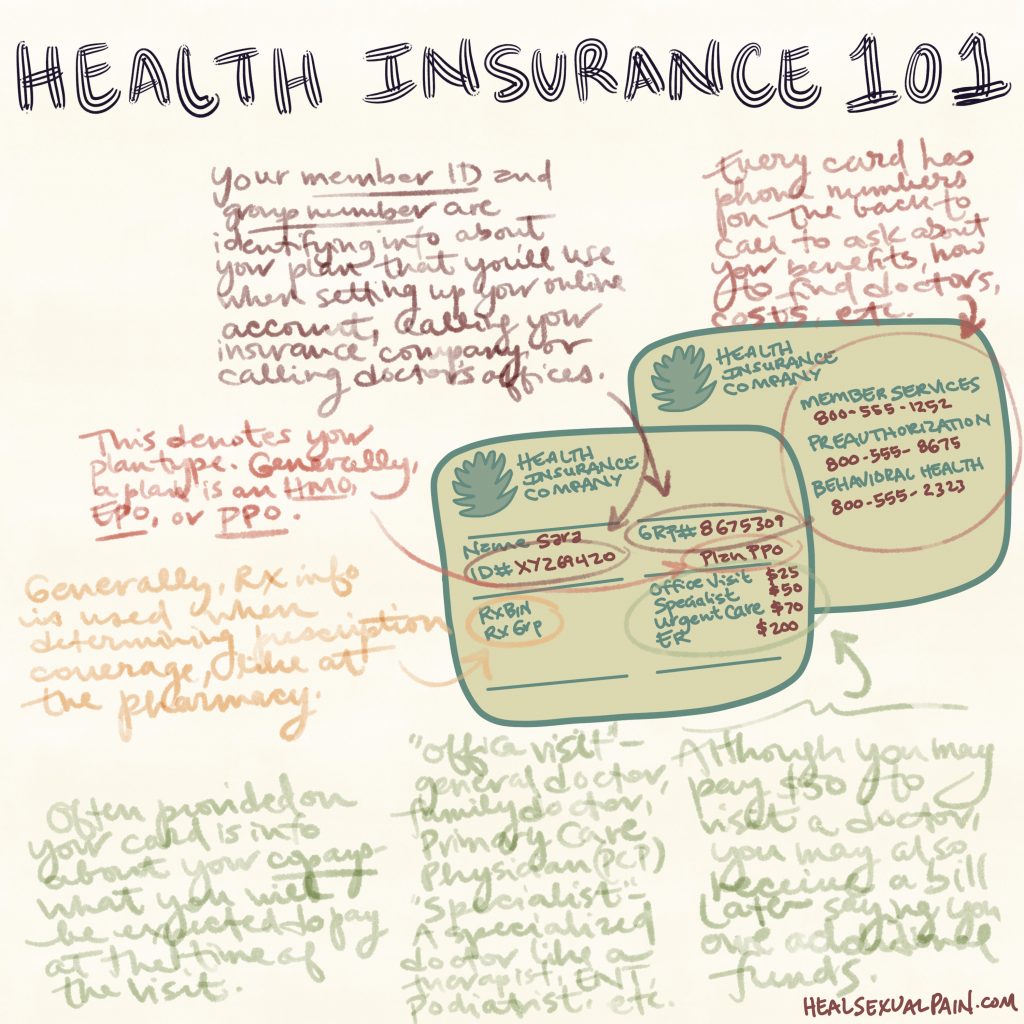

Generally your insurance plan will mail you a card each new year. On it is a bunch of information that’s necessary to provide to medical professionals you may see, and pharmacists when you get some prescriptions. Otherwise, your only use for the card is generally to review copay and other financial information, and to have access to the phone numbers on the back of the card.

Always keep your insurance card in your wallet. It’s also a good idea to have a copy of it on your google drive or other cloud service in case you lose or misplace it. Most places should be able to accept a photo of the card or a newly printed paper copy.

Decoding an EOB

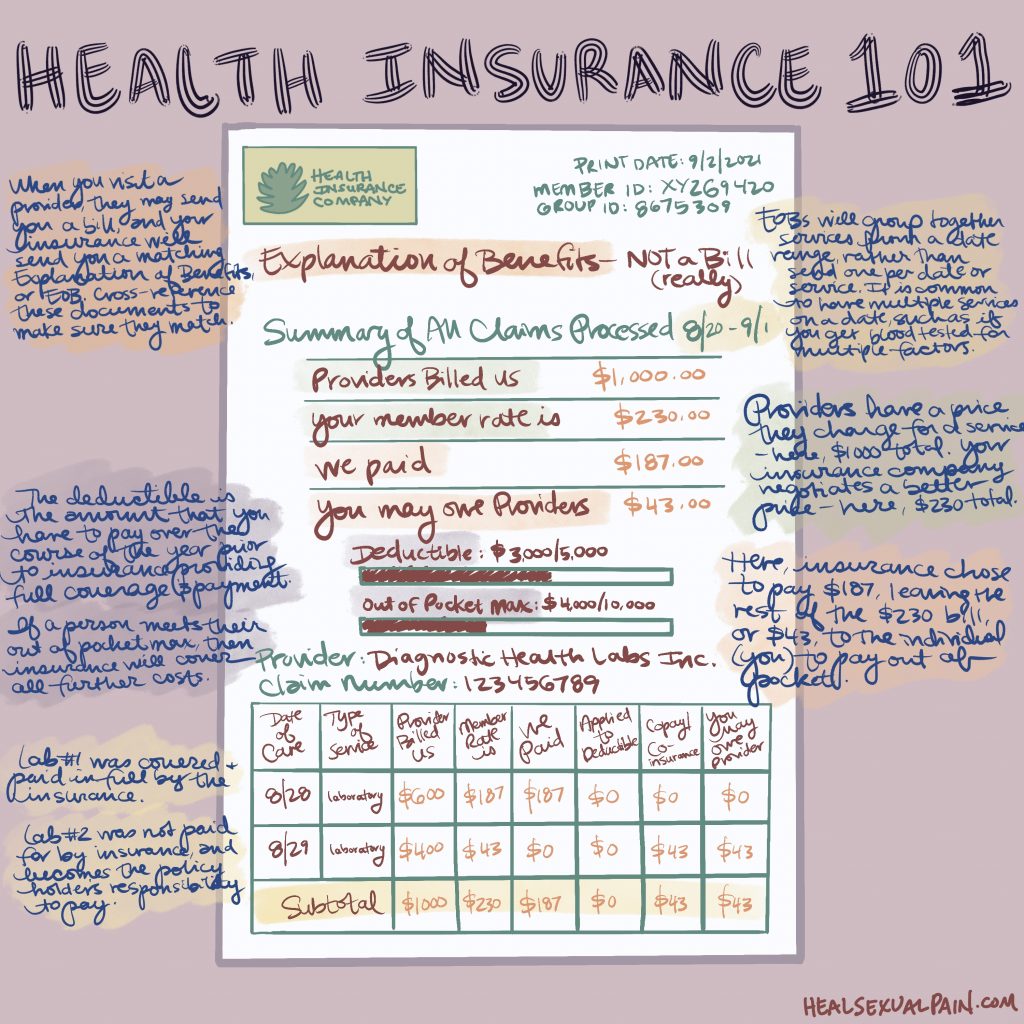

After you see a provider, your insurance will mail you an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) document that covers that date and whatever claims the provider put into your insurance company. The EOB has financial and health information on it.

Read your EOBs when you get them. Ensure you understand your care, and that all that’s included lines up with your experiences of going to the doctors (dates, procedures, and financials).

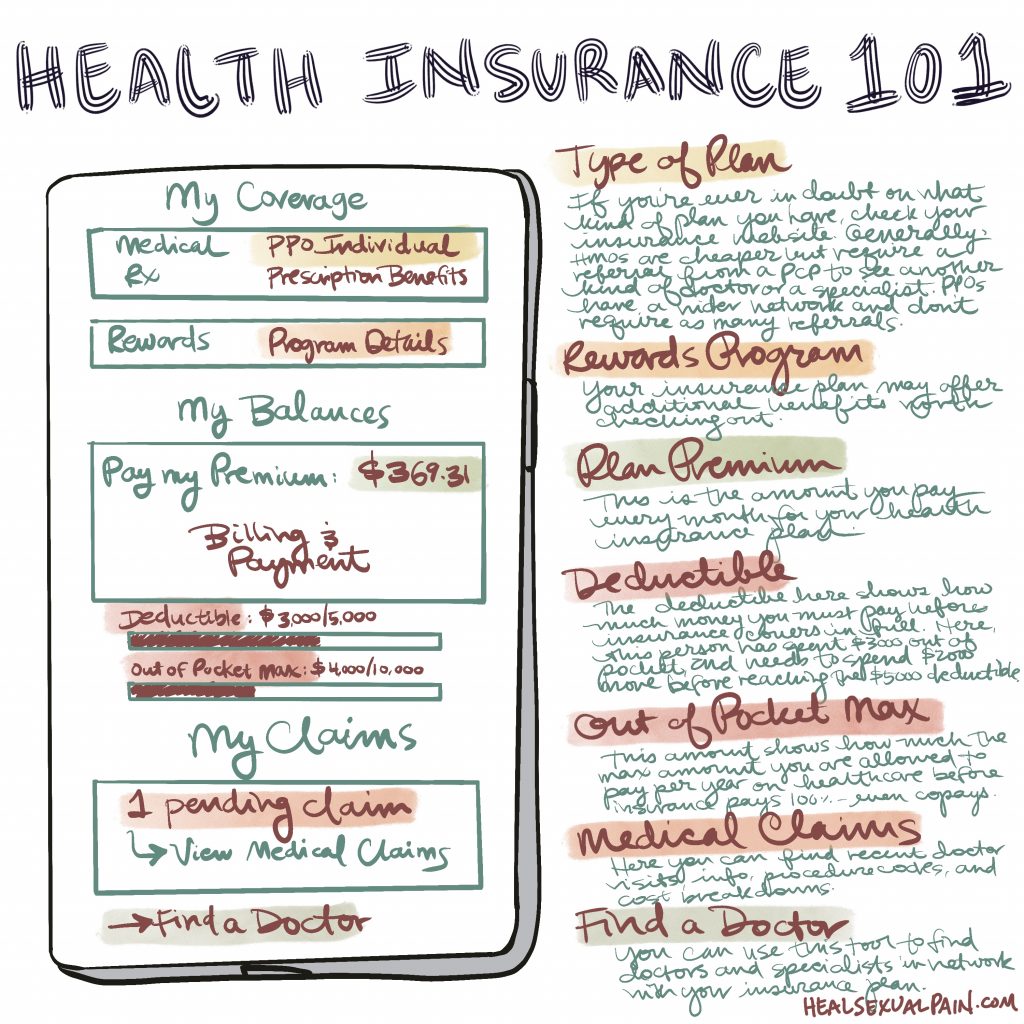

Navigating your Insurance Website

A wealth of information can be found on your insurance website, if you prefer to take care of these things yourself and want to avoid potentially long wait times when calling your insurance company from the number on the back of your insurance card.

I’m of the belief that most folks with insurance should learn to navigate their insurance website, as it has a ton of information on it and can also help you to understand and manage your finances better. Also, you can learn about additional coverages and programs you may be eligible for, so you can take advantage of the full range of benefits that your insurance may have to offer.

In-Network vs. Out-of-Network Claims

Some providers choose to contract with your insurance company, meaning they choose to agree to be in-network, participate with your insurance company, send information over to them about you, and in return receive negotiated rates for your care. These providers would be considered in-network, and generally when you see them for procedures they cost you a copay and that amount that you spend there might go toward your deductible, too. These in-network providers may show up on your insurance website. You may need to call your insurance before seeing a provider to confirm that they are in-network to best avoid any unpleasant surprises or unexpected costs.

In-network providers often charge a discounted rate when they choose to participate with your insurance. This is why, when you get sent an EOB, there may be a “rate” or cost and then a “member rate” which is less. For example, when I got a blood draw recently, they tried to charge me $414. This would have been the amount that I would have paid if I went there without insurance. Instead my insurance rate came out to be $19. As you can see, this negotiated savings can help you out if you use insurance for healthcare. However, it is also possible to negotiate a price without insurance, which many folks don’t tell you. Wiggle room can often be found with private providers and hospitals as an uninsured person; however, you gotta stretch those haggling skills.

Many skilled providers, those who fill niches in their field, and many therapists and mental health practitioners do not contract with insurance, and charge a flat out-of-pocket fee. This can be done for many reasons: because insurance will not cover their services or care (insurance often has different, more restrictive policies for mental health care), because insurance limits the amount of visits a patient can be covered for, because insurance negotiates a price that is too low for the skilled practitioner, because insurance puts up roadblocks and barriers to care through prior authorizations and other means, and because practitioners do not want to send sensitive information on clients such as notes, diagnoses, or treatments to insurance companies who may use that information in an unsavory way, among other things.

In the case of these providers, we would consider them to be out-of-network. This means that prior to seeing them, you would contact the office to gain information on what they would charge as a flat fee for services provided. The benefit of seeing these practitioners is that there are often no surprises on price, that you know what you are getting and paying for, and that insurance will not come back around and say you owe more money, try to deny your claims, or raise your rates (a fear with “pre-existing conditions which has largely been allayed by the ACA, but my guard is unfortunately still up for). You do not get the benefit of insurance potentially covering or subsidizing your care with these providers, unless you request a receipt or superbill that you might submit to insurance.

Submitting Out-of-Network Claims to Insurance

When you see an out-of-network provider, it is best practice to ask them for a receipt, or superbill, so that you may seek financial compensation from your insurance company. This receipt should have information on it such as your name, date of birth, diagnosis code, procedure, fee, and monies paid/owed, as well as your provider’s name, tax identification number, license number, and address.

Many people take this receipt and submit it to their insurance company for financial reimbursement, whether in part or in full. These benefits differ from insurance plan to insurance plan; generally it is advisable to reach out to your insurance to get an idea of your out-of-network benefits as well as the method to submit receipts. Some insurances cover services after a certain deductible has been met, others reimburse a percentage, such as they pay 85% and you pay 15%. Some insurances ask for a receipt after every visit, some will accept one superbill that covers a period of 6 months to a year, some you can submit monthly — it’s up to insurance guidelines and personal preference. Generally, if you paid the provider in full, the insurance will pay you back; if you did not pay, the insurance will cut a check to your provider.

There’s also a service I’ve found that can help bridge the process of submitting claims to insurance, called Better. It’s my understanding that you send them a picture of a superbill/receipt from a provider when you get one, and they use that information alongside your insurance info to submit the claims on your behalf. This can be good for folks who want to cut out some of the work of contacting your insurance directly to submit claims. Better takes 10% of whatever money you get reimbursed, and they take 0% if you do not get reimbursed or the money goes to a deductible.

In summation, health insurance is a lot. There’s no expectation for you to understand all this in a day — most folks learn this the hard way, after years of struggle, chronic health issues, or a giant bill or premium that was hard to understand prior. This system is designed to be inaccessible and frustrating. Learning about your health at your own pace is an acceptable and well-worthy activity, but also exhausting. Give yourself some space and grace to not have to be perfect at it while you figure it all out. I wish you well.

Update 8/3/22: John Oliver recently did a piece on the mental healthcare crisis in America and largely discussed issues with access to care, affordability, and health insurance that feels particularly relevant, which I will include below.