It’s all in the family — A review of herpesviruses and STIs

OK, let’s go over a bunch of information, and take it slow.

First off, I’d like to acknowledge that there is a great deal of shame and stigma surrounding sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

If you’re reading this, you likely have either been affected by an STI, or know someone who has. You’ve likely dreaded getting an STI, heard jokes about STIs, and been told shaming information about STIs in school or from other sources that taught you about sex. You’ve likely heard from sexual partners, or asked them yourself, “Are you clean?” without any regard for the impact of that statement.

I grew up in this culture, too. I understand this is one of the hardest conversations to have. And yet, it is a necessary one, because by age 25, one in two people will have contracted an STI, in our country.

The CDC released a study this year confirming that in 2018, on any given day, about 1 in 5 people in the US had an STI. This study also confirmed that of the ~26 million new infections yearly, about half occur in folks aged 15-24.

In this article I am referencing the Herpes Simplex Virus, which I’ll shorten to HSV. HSV infections can be caused by two types of viruses, here called HSV-1 or HSV-2. HSV infections occur on the mouth, which we would refer to as oral herpes (also known as cold sores), and on the genitals, which we would refer to as genital herpes. HSV-1 most often causes oral herpes, but can also present genitally. HSV-2 almost always presents on the genitals. Some people use the shorthand OHSV to refer to oral herpes, and GHSV to refer to genital herpes.

Herpes Viruses present several infections to humans, including the aforementioned, varicella zoster infection which causes chickenpox and shingles, epstein-barr virus, and human cytomegalovirus, among a few others which you can check out on the fun herpes family Wikipedia page. So basically, they are annoying viruses from a family we hate, that infect almost all people on Earth, that then go on to live latent in our bodies after infection. Great, love it.

Fine Print

This article is informational only and not intended to diagnose or treat HSV or any other STI. I took care to include sources for claims and other related resources but this information is constantly changing as research and practices change. That said, I am not responsible for any errors, omissions of information, or related consequences for readers of this article. If you have an updated statistic or helpful resource, I welcome you sharing it with me. I highly recommend you doing your own research on STIs including HSV, and consume information from multiple, up-to-date, and scientifically reputable sources.

This applies to the majority — HSV Statistics

Prevalence

So, I’m going to go over some boring-ass numbers and sources. Some match, some disagree, multiple sources have multiple numbers, it’s all very annoying.

The tl;dr of this section is, a fuckload of people have herpes. And it is almost more “normal” to have a herpes infection than not, number-wise.

Worldwide, ∼90% of people have one or both viruses.

An estimated 3.7 billion people under age 50 (67%) have HSV-1 infection globally.

An estimated 491 million people aged 15-49 (13%) worldwide have HSV-2 infection.

It’s estimated that 18.6 million people are infected with HSV-2 in the US, with around 572,000 new infections occurring annually.

Around 56% of people over the age of 14 in the US have an HSV-1 infection.

Estimates put it that about 1 in 5 people in our country have a genital herpes infection. About 90% of people infected with herpes don’t know it.

Some recent studies suggest that 20%-50% of genital herpes is caused by HSV-1 and this may be proportionally increasing. Other sources would tell you that HSV-1 accounts for over 50% of newly diagnosed genital HSV infections. Why is this? Probably because our culture decreased oral HSV-1 infections by increased knowledge about it which lessened its transmission but, in doing so, lessened folks’ protection from getting HSV-1 genitally. And also, this could be due to increased trends in folks performing oral sex. I wouldn’t be one to disagree with eating the booty like it’s grocery but this may lead to some unfortunate consequences, like anything else in life, I suppose.

Herpes numbers are underrepresented — almost 90% of folks with herpes are undiagnosed. That’s in part because a study found that in over 80% of people, herpes never has symptoms. It’s also because our tests for herpes suck, and often have false positives or negatives, and also are not encouraged for people to get, as most places only test for herpes after a person’s first outbreak. It’s a whole ass mess. And it’s part of the reason it is so prevalent. And also, herpes’ prevalence is part of the reason why testing isn’t emphasized. Think about it: you and I can go to the doctor to get a blood test, likely that we have to pay out of pocket for. And it’s likely that one or both of us will test positive, whether truthfully so, or in error. That will lead to a lot of stress for little reward. Cool cool cool, we might get bumps on us that are incurable?? It seems public health does not care much about herpes. Both because it’s financially disincentivized in favor of treating other problems, and because herpes is not a big deal, symptoms-wise. (It is a big deal, stigma-wise. But we’ll get to that.)

Transmission

HSV-1 and HSV-2 spread through contact with shedded virus, whether through a sore or lesion (also known as an outbreak or OB), genital or oral secretions, or virus that is asymptomatically shed through the skin. HSV spreads through skin-to-skin contact. You cannot get HSV from a toilet seat, towel, sheets, pool, or whatever — it spreads from skin-to-skin.

Generally, HSV-2 spreads from genital-to-genital contact, and HSV-1 spreads from oral-to-oral or oral-to-genital contact. Per an email exchange I had with the CDC, it’s hard to ascertain the likelihood of spread of HSV-1 from the genital area, both because it sheds so little from there, and because partners generally perform both oral and genital sex so it’s hard to determine where the spread occurred from. Up-to-date information on this is sorely underrepresented in online literature, despite HSV-1 making up a large portion of new genital herpes infections. More on this later.

The rates of transmission have been measured, albeit with some bias. Rates of transmission differ based on type of virus, location of the virus, and whether sexual partners are male or female (medical literature sorely lacks information on non-cishet folks). In her book, Terri Warren notes, transmission rates of genital HSV-2 from male to female have been studied to be anywhere from 7%, 16% or 31% in a year, whereas female to male transmission is less, around 4%. Rates of transmission of genital HSV-1 would be lower as the virus tends to have less outbreaks and less asymptomatic shedding.

The trouble of diagnosis

In my brief rant prior, I complained about diagnostic processes in the US. I’ll try not to complain for this whole section, but no promises.

It’s widely accepted that most herpes cases go undiagnosed. And while this study says that over 80% of folks don’t receive a formal diagnosis for HSV-2, it’s likely that that number may be even higher for cases of HSV-1, since it is more likely to be asymptomatic.

Herpes just doesn’t have symptoms that often in folks. And sometimes, looking at you USA, it’s hard to go about obtaining a diagnosis in the first place.

Most places offer a diagnostic test of symptomatic herpes. This looks like: you see a bump, you go to the dreaded doctor visit, the doctor is like, “yup that looks like it,” does a scrape of the lesion, sends it in for a test, and the test later confirms whether that spot was shedding the virus or not. Cool. (Also horrible and potentially the worst day of someone’s life so far because of the wild amount of stigma we place on STIs, especially herpes. But I digress.)

This leaves out a bunch of folks who may want to know their STI status absent of a symptomatic infection of herpes, or a present lesion. Like, if you’ve had a bump in the past, but don’t any longer, the doctor cannot do a swab to test for herpes. Even more complicating is the fact that many doctors do not test for herpes unless there is an active outbreak. So, if you don’t have a bump in the moment, it seems that most people’s access to information about their herpes status is extremely limited.

I’ve discussed this problem with a few diagnostic offices and sexual health professionals in my area after learning more about herpes. And I found that this sort of testing is disincentivized. There’s not much in the way of money or grants for research on, or prevention of, herpes like there is for HIV. And that makes sense, because that’s a much more drastic, life-altering infection, no doubt about it. So for the most part, when folks go to get STI tested, at least in this slice of time in this particular area, they get the “all clear” from a “comprehensive” STI test without getting results on their herpes status. I come from a background of public health, where prevention mattered much more than treatment. So this feels extremely frustrating to me.

That said, folks can get tested for their HSV status absent of a current outbreak, though it can be a bit more nuanced. A doctor like a primary care physician can order a blood test for HSV, and in some cases, places like planned parenthood can offer referrals too (many do not offer blood tests for HSV on site, I’ve learned). Then folks can go to a lab or a hospital for a blood draw that may or may not be covered by insurance, and may potentially cost hundreds of dollars. Do you see all the bottlenecks to getting a diagnosis? There’s even more, but let me stop here for a moment. Getting a blood test for HSV is hard. That’s a major reason why it goes undiagnosed so often.

There are some services that can offer an HSV test for a flat cost — a good one I’ve learned about is Any Lab Test Now (this business name makes it sound like a scam, but whatever, I’m not their marketing person).

So, there are two readily available blood tests for HSV, which test for antibodies which will tell whether your body has seen this infection before. There’s a test that looks for IgG, or Immunoglobulin G, which appears up to a few weeks after a first infection and then stays there for life. And, there’s a test that measures IgM, a first antibody that appears after an infection but then disappears.

Every source I could possibly Google recommends the IgG test over the IgM test. The American Sexual Health Association breaks it down for these reasons:

- Many assume that if a test discovers IgM, they have recently acquired herpes. However, research shows that IgM can reappear in blood tests in up to a third of people during recurrences, while it will be negative in up to half of persons who recently acquired herpes but have culture-document first episodes. Therefore, IgM tests can lead to deceptive test results, as well as false assumptions about how and when a person actually acquired HSV. For this reason, we do not recommend using blood tests as a way to determine how long a person has had herpes. Unfortunately, most people who are diagnosed will not be able to determine how long they have had the infection.

- In addition, IgM tests cannot accurately distinguish between HSV-1 and HSV-2 antibodies, and thus very easily provide a false positive result for HSV-2. This is important in that most of the adult population in the U.S. already has antibodies to HSV-1, the primary cause of oral herpes. A person who only has HSV-1 may receive a false positive for HSV-2.

- IgM tests sometimes cross-react with other viruses in the same family, such as varicella zoster virus (VZV) which causes chickenpox or cytomegalovirus (CMV) which causes mono, meaning that positive results may be misleading.

The IgG test is better for folks who want to know the real facts on their HSV status — it detects antibodies with more precision than the IgM, and can more accurately tell whether someone has antibodies for HSV-1 or HSV-2. Even so, the IgG test still has varying degrees of accuracy: it cannot measure antibodies soon after infection, as the body must mount an immune response, so it is not useful in newly infected individuals until a few weeks or months down the line. The IgG test also comes under fire for creating false positive diagnoses, particularly when someone’s antibodies test near the baseline. And, the IgG test will not indicate where in the body the infection occurs — so if you get a test for IgG and pop positive for HSV-1, for example, you will not know whether you have it orally or genitally or elsewhere in the body. This also disincentivizes testing for some folks, because it may present stressful or stigmatizing results that are not necessarily accurate.

A test also cannot accurately tell when a person has gotten an infection. There can be clues, in some cases. For example, say a person who has an initial outbreak, and gets a swab of the sore and a blood test, comes back negative on their IgG but the swab tested positive for HSV. It is likely that it is a new infection, as they have HSV, but their body has not had enough time to mount an immune response yet, so they don’t have antibodies. This person will be able to retest IgG in a few weeks or months to learn more about what type of HSV they have if the swab did not offer that information.

However, if a person gets a test and has never had an outbreak and tests positive, they cannot know when exactly they became infected. And, if a person has a first outbreak and tests positive on the IgG at that time, it is likely they were infected prior and just never expressed it before then. So it would be nearly impossible to narrow down when transmission occurred, unless they only had sex or touched faces or whatever once. Herpes viruses, once contracted, lay dormant on nerve cells and only express once in a who-knows-when. A person can be infected and not have an outbreak until some time down the line.

The most recommended test for HSV by expert Terri Warren is also the hardest to access: the Western blot test. This test is generally for confirmatory results or on-the-line cases, and is only performed at the University of Washington. She recommends this test for people who test low positive on an IgG test who want confirmation of their negative or positive status, or even if folks get a negative IgG, citing that the IgG test misses 8% of HSV-2 infections and 30% of HSV-1 infections.

It’s clear to see that there are many problems inherent in HSV testing and diagnosis. It’s hard to obtain a test, and it’s hard to know when the test is accurate, and it’s hard to know what the test indicates even when results are present, and it’s hard to know where to go from there once a result is received. Let’s review some more information in the meantime.

HSV-1 vs HSV-2

It’s important to understand the similarities and differences between Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and 2.

Both viruses present largely without symptoms most of the time, and in most people who have the virus. The virus lives in the body’s nerve cells, or neurons, where it hides from the body’s immune response, which makes it hard to impossible for the body to control or eradicate the virus. It can then travel up the neuron periodically to cause a symptomatic outbreak at the site of infection.

When symptomatic, the viruses can cause blisters to appear on the body’s skin and mucus membranes (mouth, lips, nose, genitals, anal area, inner thighs, nipples, eyes). Lesions can be productive and wet, and then scab over before healing.

The frequency and severity of outbreaks depends on the person’s immune system and personal biology, type of HSV they are infected with, site(s) of infection, and environmental factors and stressors. Some people never have an outbreak, some go years between, some have outbreaks more often.

Transmission of the viruses occurs when there is viral shedding from the body: the virus reproduces and then can be transmitted with skin-to-skin contact. Both viruses shed readily when there is an active outbreak. Both viruses also asymptomatically shed, which means transmissible virus can be periodically released without manifestation of symptoms.

Again, HSV is extremely unlikely to shed from surfaces like a toilet seat, because the virus begins dying once it leaves bodily surfaces.

Having the virus infecting one area makes it much less likely to acquire it in other areas. However, self-to-self transmission of the virus can occur; this is known as auto-inoculation. A person gets initially infected with HSV in one area, where the body first came into contact with the virus. This is called the primary infection. The virus then lives latent in the body, as aforementioned. Theoretically, an infected individual might touch a sore in one area, and then touch another area of their own body, prompting a new infection in a new area. This is most likely around the time of, and soon after, primary infection. After some time, the body develops enough antibodies to recognize and fight the virus that it is very unlikely for the virus to spread from one area of the body to another in the same individual. For example, if person A transmits oral HSV-1 to a partner B’s genitals, and that person B is primarily infected, it is unlikely that person A will then develop GHSV-1 if they continue to have sex. However, it is possible that newly infected partner B may acquire an oral infection if they touch their genitals and then mouth. If person C has an established case of OHSV-1 and person D has an established case of GHSV-1 they can participate in sex without worry of transmission, according to Terri Warren. However, the process of auto-inoculation is still being studied. The biggest concern with autoinoculation is that a person might transmit HSV to the eyes, which is much more troublesome than oral or genital infections.

A primary infection of HSV generally presents with an outbreak if a person is symptomatic. This can include the presentation with sores and lesions. In the primary outbreak, a person may also present with flu-like symptoms, including fever, headache, fatigue, body aches, and swelling in the lymph nodes, because the body is mounting an immune response to attack the virus. The primary outbreak is often the most dramatic, with subsequent outbreaks being less substantial as the body’s immunity to the virus becomes stronger. The frequency of outbreaks decreases over time, also.

Following outbreaks may be spurred on by environmental factors, like stress, sunburn, fatigue, other illnesses, immune system changes, trauma, sexual activity, hormonal changes, menstruation, and dietary choices, among other things.

It is possible to acquire both HSV-1 and HSV-2. However, having one virus makes it more likely that your body has antibodies to fight new infections. Therefore, persons infected with one type of HSV who acquire the second type are much more likely to have reduced or no outbreaks from their newly acquired second HSV infection. It seems the general rule of thumb that folks with HSV-2 need not worry about HSV-1, however folks with HSV-1 should still be cautious about getting HSV-2. Terri Warren states that “a person who has HSV 1 genitally can still acquire HSV 2 genitally (the reverse almost never happens).” However, the antibodies developed to HSV-1 are likely to keep the new HSV-2 infection under control and less symptomatic than a person who acquires HSV-2 absent of established HSV-1.

HSV can be transmitted from parent to child during birth and so this should be addressed with doctors and treatment team for best recommendations. That said, how to manage HSV during pregnancy has been well studied because a third to a fourth of adult pregnant women manage a genital HSV diagnosis. Both types of HSV also increase one’s chance of acquiring HIV from an infected partner, which makes practicing safer sex more important for infected individuals, as well.

There are some key differences between the two viruses:

HSV-1 is more prevalent in the worldwide and US population. It “wants” to live on the oral area, where it has more outbreaks and asymptomatic shedding, and so transmission occurs more readily also because people are more likely to contact this area on other humans, from kissing or incidental oral contact or brushing. Oral HSV-1 is often acquired during childhood, from incidental contact with other children or infected adults. Genital HSV-1 is most often acquired from a person receiving oral sex from an infected individual. HSV-1 expresses more often orally than genitally, causing more oral outbreaks, and shedding less on genitals than it does orally.

HSV-2 is primarily a sexually transmitted infection, and because it “wants” to exist in human genitals, it sheds most often there. Its prevalence is less than HSV-1 for this reason. HSV-2 is rarely transmitted orally, because the virus does not “want” to be there as readily, although it is possible. A major difference between the viruses is that while HSV-1 is the case for many new outbreaks, HSV-2 causes recurrent outbreaks.

The viruses have differing likelihood of outbreaks. “The recurrence rate for genital HSV-1 infection is about one outbreak every other year vs. HSV-2 genital infection that recurs 4-6 times per year.” If a person has recurrent outbreaks genitally, and do not know their HSV status, it is most likely they are infected with HSV-2 rather than HSV-1. In cases of GHSV-1, if a person does not have another outbreak in the year following their first, it is an 88% likelihood that a viral outbreak will not recur again.

The viruses also differ in rates of shedding, and therefore rate of transmission is different. Terri Warren states the asymptomatic shedding numbers as follows —

HSV-2 genital — 15-30% of days evaluated

HSV-2 oral — 1% of days evaluated

HSV-1 genital — 3-5% of days evaluated

HSV-1 oral — 25% of days evaluated

Studies on transmission are lacking, and numbers are crude. Unfortunately, most studies are done on cisgender heterosexual couples. The numbers can be mildly helpful in understanding risks of transmission present when participating in PIV (penis in vagina) sex with infected partners. When partners were studied having sex only when an outbreak was not observed, “Overall, the risk is about 10% per year that an infected male would transmit HSV 2 to an uninfected female. That is, if 100 infected men were having one-on-one sex with 100 uninfected women, about 10 women would get infected per year. If the situation were reversed, about 4 uninfected men would get herpes in a year from infected women.” Using condoms cuts the risk of transmission in half, and using suppressive antiviral therapies to manage outbreaks cuts that number about in half again (see Warren’s book pg 37 for more information on the related studies).

Terri Warren notes that up to 70% of new cases of herpes are transmitted asymptomatically. So understanding asymptomatic spread is important to taking increased precautions to protect partners.

That being said, HSV is extremely prevalent, testing is hard to come by and can be inaccurate, and methods of prevention are not always effective. The reality of being infected with herpes is real for most humans on this Earth.

It can be said that all people who have herpes got it from someone else. If we cast aspersion on, and stigmatize, all people who have HSV or have transmitted it, we would have to do that to most human beings. HSV is a reality of life. It is of course important to protect oneself as much as possible, in all aspects of life, including sexually. However, the fact that HSV is so prevalent means that for some people, acquiring and living with the virus is just a reality of life. Fortunately for them, the virus most often can be considered a mild infection. The social stigma of having HSV is clearly its most impactful symptom.

Physically, it ain’t a big deal — outbreak primer

So what’s an outbreak actually like?

Many of us learned about STIs in sex ed in school (if we were so lucky to hear the dreaded “S-word” at all in school) and were treated to fear-based “education” tactics where we were subjected to a picture of a penis so infected it looked like it might fall off, or a vulva that was hardly distinguishable from a bowl of spaghettios. Subsequently, we went home and scoured our own genitals, fearing for every ingrown hair or zit that dared show itself down there.

The reality is, there is a range of intensity for outbreaks, just as there is for frequency.

Most folks infected with Oral HSV-1 are well-versed in it, as it’s most often acquired during childhood, and is well-documented in online literature (I can easily google some person’s lips without my freaking safe search turned off or whatever). So I will focus on genital presentations of herpes for the sake of this article, as it’s more often and more likely to be steeped in fear and misinformation.

A genital outbreak of HSV may be asymptomatic at best. From there, a symptomatic outbreak of HSV may present with only one, or more, sores. Other words used to refer to them are blisters, vesicles, ulcers, or lesions. These can look like a pimple or ingrown hair, small, red, swollen, or a whitehead, as the vesicle develops fluid and can be opened and leak in a similar fashion. It is in this way that doctors can test the sores to see if they are shedding the virus. After such an expression, the sores generally crust over and fall off, and the area returns to the appearance it had prior to the outbreak. This generally happens over the course of several days, although a primary outbreak may last weeks. Prescribed antiviral medication can shorten this process. While present, the lesions may be sore and painful, itchy, or have a weird zappy nerve feeling associated with them. Sores may be individual, or they may form small clusters.

Outbreaks generally occur in the same location although the virus may choose to move along a new nerve to a new, but related, location. Genital herpes viruses live on the sacral ganglia nerve, which innervates the “boxers area,” so basically anywhere boxers shorts may be, an outbreak can arise once infected. This includes inside the penis and vaginal canal, where they may not be seen or noticed.

Many people with HSV experience what is called prodrome, or a prodromal period. This refers to a time before an outbreak manifests where a series of symptoms may indicate an oncoming blister. Both oral and genital HSV may present with prodromal symptoms hours or days before expression of HSV. Folks with GHSV may experience genital pain, or tingling or shooting pains in the legs, hips or butt. People who have HSV and have become familiar with it and their symptoms may be able to predict an oncoming outbreak if they experience prodrome and are in tune with the bodies and symptoms.

HSV lives on the nerves while it lies dormant. It may be associated with nerve pain, and nervous system problems, including chronic pelvic pain, however these links have yet to be explored readily.

There is no known cure for HSV. It lives on nerve cells and lies dormant most of the time, making it hard for the body to predict, and so the immune system cannot entirely eradicate the virus from the body. However, there are antiviral suppressive treatments for HSV that intend to lessen outbreak frequency and intensity as well as lessen duration of symptoms. Some people choose to take antiviral medication daily, which can suppress the likelihood of an outbreak. Some people take medication when they feel prodromal symptoms coming on, and some people take medication when an outbreak occurs in order to lessen the period it takes to heal. Many, many people do not take medication at all. It can be surmised that people are more likely to take medication if they have a more expressive case of HSV, which is more likely with genital HSV-2. Some people also choose to take medication to lessen chances of outbreaks and viral shedding if they intend to have sex with partners and want less of a chance of transmission.

The antiviral therapy drugs that are approved to treat HSV are Acyclovir (Zovirax, generic), Valacyclovir (Valtrex, generic), and Famciclovir (Famvir, generic).

Some folks pursue alternative treatments for HSV. This area of study is less well-known, and I will briefly mention some things, however, please note that this is not medical advice. This piece is meant to inform regarding the ins and outs of HSV, based on scholarly sources I’ve pored over. There is a huge community of folks worldwide, billions, who manage HSV. Of course they would like for there to be an option to relieve them of symptoms and problems caused by the virus, most of all, its associated stigma. There are some people who push “cures” for HSV that are not helpful and not backed by medical science as we understand it. There is no known cure for herpes. The community of people affected are encouraged to wait until a better answer comes along, spurred on by scientific research and study.

There is some evidence to suggest that supplementation of the amino acid L-Lysine can lessen duration and severity of outbreaks or assist in their prevention. This area of understanding needs more study.

There are now vaccines for chickenpox (varivax) and shingles (shingrix), which are also viruses in the herpes family. This bodes well for folks’ hopes that a vaccine for herpes may be an option someday. Furthermore, the ongoing development of mRNA vaccines and associated technology spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic may also push the community in a helpful direction while continuing to study HSV and develop treatments for it.

For now, the folks who manage infections of HSV, no matter the location, must cope with the virus both physically and mentally. This means managing outbreaks, practicing safer sex as indicated, disclosing to partners, and managing the stigma associated with HSV.

Socially, it can feel like your life is over — managing stigma & disclosing

Society’s treatment of STIs, and those affected by them, is understandably steeped in fear, but exaggeratedly so. STIs if left unnoticed or untreated may result in a host of damaging physical symptoms, infertility, and death, among other things. With that being said, herpes presents to the bearer an occasional, low-grade host of physical symptoms, if that. Its main damage done to its inhabitants is psychological and social.

There is an ethical responsibility to those with STIs to disclose their diagnosis (if known) to potential sexual partners in order to obtain true consent before proceeding with sexual activities.

This means for bearers of this virus (yes, even you, oral herpes crew) that they must disclose their status to their partners, which can present an understandable hurdle to sexual activity or intimacy of any kind with others. Some people managing HSV feel they must remain celibate lest they burden others with the condition. Others feel intense fear at disclosure which inhibits them from talking with or becoming close to other people. Some people choose to hide their status or not mention it, removing others’ agency for true consent and potentially putting others at risk for developing HSV.

There are some legal ramifications to people who choose to engage in sexual activity without disclosing their STI status and infecting others. This is what I’d call an external motivator to telling. Here, I hope to appeal and speak more to folks’ internal motivation to disclose: in my opinion, it is the ethically right and necessary thing to do.

If you agree with me, then we can agree — outside of living a totally celibate and emotionally closed-off existence for the rest of time, then, HSV-havers will have to disclose their STI status at some point or another. So let’s talk about that in relation to this societal stigma that exists in our culture.

Having an STI, and in the case of this article, HSV, does not make a person undesirable, ugly, disgusting, gross, or a burden to be with. Accepting a person’s STI status is not a bargaining chip, a manipulative tactic, something someone should be thankful of, or a quid-pro-quo exchange. Having an STI does not lessen someone’s inherent worth or value. One does not have to “compensate” for having HSV. Billions of people have HSV worldwide. You 100% know someone who has HSV, whether you know it or not. People with HSV still live productive lives, are attractive, love others and are loved, and have bangin’ sex with orgasms and all that.

Society and pop culture’s treatment of STIs and herpes is cruel and unfair. It is based in dehumanization, misogyny and misandry, homophobia and transphobia, misinformation and lack of education and exposure, shame, and most of all, fear.

Having a diagnosis of HSV makes sex, dating, and relationships more complicated in that people have to have more courageous conversations around uncomfortable topics. People might not like that. Potential partners might say no. You might have to think more about how to have safer sex. You might need to have safer sex more often, which can make sex feel less “free.” You probably won’t have sex during outbreaks when HSV is most transmissible. You might need to think about HSV more often, whether it’s talking about it with friends or partners, discussing with medical professionals, processing and dealing with your own feelings, learning about and researching HSV, or managing outbreaks. Life is not the same after receiving a diagnosis of HSV. However, you may be surprised at how similar it can be, particularly once you’ve processed the experience, managed the grief, and returned to your life.

This is demonstrated in the scant research; newly infected folks experience intense negative psychological symptoms, but most return to normal functioning within 4 to 6 months, having had time to process the diagnosis and all that.

A big thought process that HSV-affected folks might have, particularly when considering interacting sexually with folks who (presumably) don’t have it, is the preoccupation with the guilt and fear of, “What if I pass this along to someone else.” Absolutely. You are an ethical person who has empathy. You know what it was like to sit in that doctor’s office, and understandably, you never want to put someone else through that. HSV is a reality of life for most human beings. That statement is not to lessen its severity, nor is it a plea to entertain a lasseiz-faire attitude toward the virus and your sex life. What it is, however, is a fact. People will consent to sex with you knowing the facts. And it will present a risk. And you may transmit the virus to a partner who consents to sex with you and understands the risks associated.

There’s likely no sense to going through life being like, “Well, I never had sex again, and was alone for my lifetime. But at least I never potentially gave someone small bumps on their genital area.”

So, you’re stuck with still having a sex life, most likely. But you have to deal with the overwhelming feelings you may have when thinking of your diagnosis. And you may have to manage the horror of discussing it, and being vulnerable with, someone else.

There’s a lot of feelings there! You may be like,

“Why me??”

“They must have gotten it wrong.”

“How could that person do this to me?!”

“My life is over.”

“I hate myself.”

“This is all my fault.”

“I’m going to be alone forever.”

“I’m disgusting and broken now; no one will like me.”

“What if everyone finds out?”

“I can never get oral sex again :(“

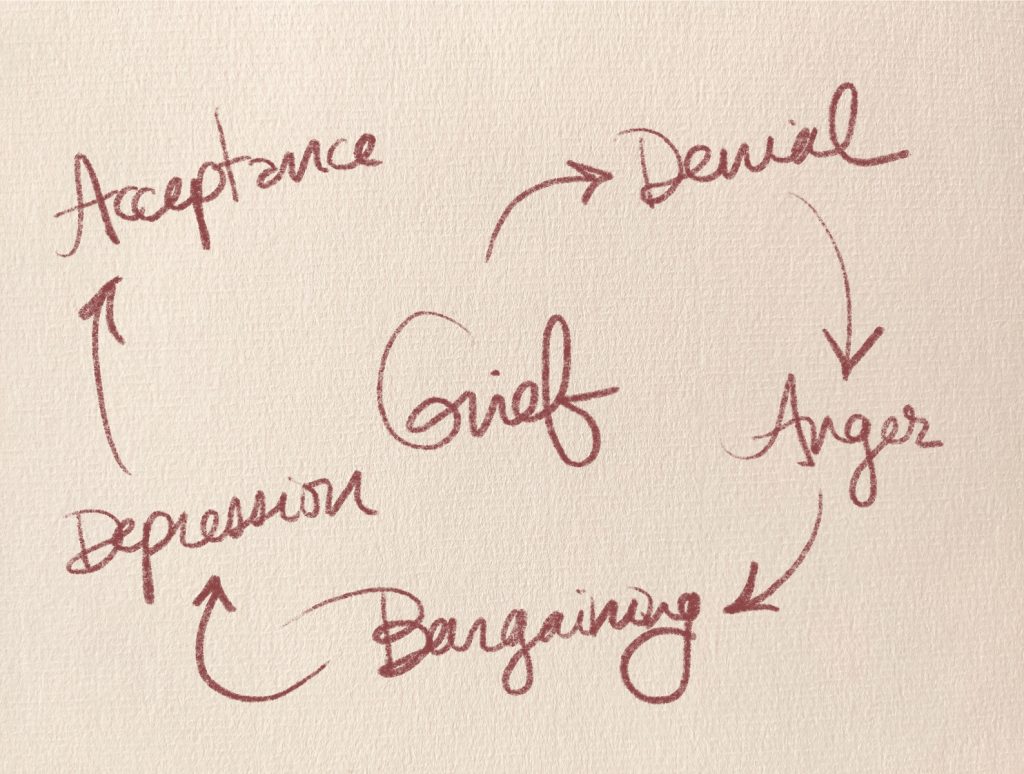

People managing new knowledge of a herpes infection certainly go through the cycle of grief. You’ve probably heard of this, it’s a well-known model. Having your own perception of your health information change, and your sex life change, certainly, and rightfully, can cause someone to grieve!

Denial

Getting hard-to-swallow news will always come with an initial reaction of disbelief. Feeling that it can’t possibly be true, it can’t be happening to you, the doctor or the test must have gotten it wrong, are totally normal reactions to hearing news that feels Earth-shattering. Feeling surprised, afraid, and confused are normal. It’s likely that you didn’t know much about the virus before, outside of some tired jokes and horrifying health class images. It’s likely that you didn’t know it was so prevalent and so many people, including people you know and love, manage this diagnosis too. It’s ok to give yourself time to process these feelings, to learn, and to double-check, and to just sit with the horrifying and overwhelming feelings of grief, fear, and disbelief.

Some folks sit in denial for a while. That first bump may appear and the person, mortified, may choose to retire to bed in their pajamas for two weeks, until the outbreak ends and they can pretend it did not happen. Some folks choose to deny the diagnosis, not going to the doctor or getting a test, because they figure they can live their life without the confirmation of the news, as it was before, pushing the negative feelings down. I caution against this approach. It just feels terrible, and potentially puts others at risk, as well as the person in question, who may be managing a different or more harmful STI altogether. If this has been the case for you, it’s understandable. However, getting “the news” is a step forward in healing, rather than pounding down the negative feelings in hopes that they will disappear.

Anger

Anger is an understandable step in the process. When getting and processing the news, there’s so much to be angry at!

You may feel angry at yourself, at your partner, at your clinician, and at society as a whole for totally being a giant douche about all this herpes stigma.

Being angry at yourself is understandable: your brain tries to create a consequence, to say, Let’s never, ever, ever let something so traumatic to us happen, ever again. I mean it this time. And that’s smart of your brain, although potentially not wise: the reality is, the large risk of contracting HSV was always there, although you likely never paid attention to it so much because you had no real need or incentive to. Even practicing the “safe” sex you learned when you were younger may not have been enough to stop this from happening. You could have taken a bunch of precautions and still ended up in this boat. The reality is, part of coping with this is learning more about this, and managing your diagnosis and health moving forward. And although there may be a bunch of anger for oneself initially, the reality is that most people on this Earth manage this virus in one way or another. So there’s no need for all humans to be angry at themselves.

Being angry at a partner is also an understandable reaction. “How could they do this to me?!” Absolutely. You may have no idea where you got the virus, as it may have happened in a time you were living it up with a few partners, or may have arisen years after lying dormant. There is potentially no way to know, or to trace the virus. You may have gotten the virus from a partner whom you knew had it, and had been taking various levels of precautions. You may have gotten the virus from someone who lied to you, or from one of the almost 90% of people who have the virus and are ignorant of it. Whatever the case, of course managing feelings of anger, blame, and finger-pointing are part of the process. It may feel easier to point the finger at someone else than looking in the mirror. With that being said, at some point in this process, a return to acceptance will be part of healing. Understand that most people on Earth manage a herpes diagnosis. Everyone got it from someone else. There are people transmitting it knowingly, poorly managing their own fear, lacking empathy, and manipulating others; there are people who are ignorant of their diagnosis due to systemic educational and healthcare problems, socioeconomic issues, and cultural biases; and there are even more having sex lives full of communication and consent around this topic. And the virus still spreads.

You may feel feelings of anger at your doctor, for never preparing you for, and cautioning you against, transmission of the most common STI there is out there. You may feel angry that HSV testing was not offered to you previously with your regular STI screenings. You may feel anger and grief at society for ill preparing you for having a childhood HSV-1 infection that you are just now learning can be easily and readily transmitted to the genitals. You may feel anger at the doctors who did not treat you with empathy, or made a remark that felt damaging regarding HSV. You may be like, “Fuck the world!!!” when you hear your one thousandth herpes joke in a movie, TV show, popular song, Youtube video, comedy bit, night out with friends who don’t know… you get me.

Whatever the case, 100%. I’m totally with you. Fuck HSV. There’s a lot to be angry about. It’s part of the process. At some point, there will come a check-in moment where you can reevaluate the amount of energy you are directing at feeling angry, and ask, Is this helping me move forward?

Bargaining

In the bargaining stage of grief, folks usually try to find some play with the bad news, in this case, the new diagnosis of HSV. They may ask questions, try to talk with some higher power, or look for meaning in their diagnosis or perceived life trajectory.

It’s understandable to try and deal with the utter helplessness of having this diagnosis of an infection that will never go away. The sad reality of it is, it’s here to stay. You’ve entered the majority now, people who manage an HSV diagnosis.

Depression

This is a big one for an HSV diagnosis. Even though I can throw that research study statistic at you and be all like, most people return to normal functioning 4-6 months after diagnosis, you know that doesn’t have to mean shit to you when you’re going through it. Valid.

HSV is a depressing reality to manage. Yeah yeah Sara, I’m in the majority, woop-de-doo. Ok, ok. It’s tough! You will have to potentially deal with symptoms ongoing, and even the prospect of them lessening and lightening over time doesn’t have to help. Knowing you’re not alone in this might not help, when you’ve just been diagnosed and you feel isolated as fuck. It’s hard to even imagine your life and what it could be, and will be, as you move forward from this. You may feel deflated, afraid, isolated, lonely, filled with guilt and shame and embarrassment and regret.

It’s ok to be in a dormant stage following this troubling diagnosis. In that time, practicing self care, giving yourself time to process, and access to things you find familiar and comfy, are important. Remembering things of your life that are the same, or familiar, can be important to keep your grip on your reality, yourself, and your identity. Taking some time off, relaxing when possible, and centering yourself are all steps forward. The world is still there for when you feel less overwhelmed and afraid. Using this time to educate yourself about the virus may help to control your fear and all feelings related.

Acceptance

At some point, you will have processed the above emotions, likely over and over and goddamn over, and be at a place where there is some more energy and more mobility. The “what now?” stage. You may want to explore what your life could be, or will be, and determine your options, as you’re just gonna keep on living, anyway. You will begin adjusting to what this “new” normal means to you. You may work toward accepting yourself and your perceived flaws.

Despite this, it’s fair to say that progress is not linear, and even once you’ve accepted a diagnosis, you will have good days and bad days. There are still thoughts and feelings that will come up that are negative around your HSV status. Your life may not ever feel the same as it did before, with regard to your feelings around yourself, your health, and your sex life. You will have a more sensitive ear around social stigma toward STIs and HSV. You will manage feelings of fear, embarrassment, guilt, isolation, shitty self-esteem, and helplessness around the diagnosis while managing this social stigma. You may find it hard to date or have sex because of these feelings and more.

All of these are understandable, even though they likely aren’t warranted. That said, it is important to tango with, and combat, some of these feelings of negative self-worth, shame, and isolation. A virus chose to live in your body, because that is viruses’ single purpose on this Earth. Like, that’s it. That’s the size of it. And objectively, that is what has happened to you.

Now, society is unfair and terrible with regard to its stigma of STIs. The same can go for systemic racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia, income inequality, go on, add your own. More than anything, society’s stigmatization of a virus that 90% of people have is the absolutely bonkers-nuts thing here. And that will be the hardest obstacle to combat.

That said, this is the major thing you have control over: even though you can’t change society (I’m workin’ on it, please join me, but it’s hard work — let’s take it one at a time), you can change you and your interplay with society and yourself. You can change your own stigma, and what it means to you. And even though you can tell me I’m a moron because that doesn’t change how horrifying that it is to disclose your HSV status to future people, the most important relationship you will have is with yourself. So #1 is making sure you aren’t unnecessarily beating yourself up over this. Other people will follow.

Disclosing your diagnosis to someone else is daunting.

“I’m terrified about talking about this. What do I even say?!”

Here’s the million dollar question!

Disclosing your HSV status can be extremely harrowing, but also extremely helpful: it opens you up to receiving support, love, affirmation, reassurance, and relieving yourself of guilt, pressure, and obligation.

The emotional burden of disclosure might never get easier. However, your readiness to do so, and your preparation and knowledge, are subject to change, to grow, to get better. So here, I encourage you to learn as much as you can around HSV, as well as to prepare for disclosure by processing your own emotions, and practicing your own communication skills.

You may wish to tell friends or family about your diagnosis.

Disclosing your status to people you care about, and people in your support system, is important so you can receive support, love, affirmation, and potentially guidance, as it’s overwhelmingly likely that you know folks with HSV.

Talking about sex can feel awkward, especially with family members like parents. The cool thing to remember is, not only is HSV way more prevalent in folks older than you because they’ve lived life and therefore had more opportunities to contract the virus, but also, older people are more likely to have contracted HSV-1 at an earlier age due to less infection control measures around a virus that was less well-known back in the day. So it’s pretty likely or possible your parents may be more familiar with the virus than you think.

And, it is perhaps most important to inform past, current, or future partners about your HSV status.

There are a multitude of reasons to disclose, including aforementioned external motivators, including potential legal ramifications, as well as internal motivators, including your own ethics around sexuality, relationships, health, and consent. Let’s dig into this a little more.

It’s likely that you would have preferred to know your partner’s HSV status prior to becoming infected, so you could have made a decision based on that. Unfortunately, most people do not have the option to know their HSV status, as aforementioned, leading to much transmission. Here, your empathy for others, and commitment to “doing it the right way” are important motivators to disclosing. Talking about your HSV and sexual health is an important step in intimacy, now just as much as ever. It can serve to increase the likelihood of you having safe and, frankly, good (as in pleasurable) sex, if y’all are more likely to discuss stuff in detail and communicate empathetically around sex and sexuality stuff. And, discussing safer sex and HSV make it less likely that you’ll transmit the infection.

Discussing your HSV status allows your partner to take in the information, process it, and understand what they are agreeing to when consenting to sex with you. This allows the two of you to decide on a sexual menu (whether completely bare or full of goodies) that your partner can provide true consent to. You can proceed to have ethical sex with HSV weighing less on your mind. And, you get it out of the way. Discussing sex stuff before sex helps to increase intimacy, trust, and pleasure.

That said, disclosure generally happens prior to a sex act with someone, once your HSV diagnosis is known. I’m not saying you need to, like, pause making out to say it, or have it be your first message once swiping right, or whatever. But, it is important to disclose before partaking in any risky activity (which might be kissing if you are prone to OHSV-1! But I am more focusing on GHSV here). I understand not wanting to project your HSV status to the world — I certainly haven’t seen an HSV one of those stupid social media picture frame things (probably because then most people would have to use it). So, it can feel best to tell a partner about HSV after knowing them and trusting them for some time. In this way, it gives folks more of a chance to get to know someone, and to know someone’s character to determine if they are likely to treat such sensitive information with dignity and grace (and honestly, doesn’t knowing this about their character this impact the potential that you will enjoy the sex with them?? No?? Just me??? ok).

You may be feeling a desire to tell someone sooner, as a gauge of their ability to be compatible with you, as a test, or as a means of getting the guilt and shame over with ASAP. That said, you aren’t “leading someone on” just for not leading with this info from the gate. Sure, it’s better to tell this before, like, having another set of genitals aiming at your genitals at midnight on a Tuesday, I agree with that, but it is ethically OK to get to know someone emotionally before disclosing your HSV status.

You may be waiting for an opening. Maybe you usually have the STI talk before hooking up with someone new — now, it will be a little different. Maybe you just heard a joking comment about STIs or herpes while out together, and it’s bothering you, and you want to check in with your partner about how they are feeling about it, to get a clue. Maybe you’ve discussed the laundry lists of weird medical stuff and back pains and gastrointestinal crap over a hearty plate of tacos and now have this one more to add to the list. Whatever the case, it is reasonable too to discuss around the topic prior to gauge a prospective partner’s feelings around it or related subjects to see if they are even someone you want to be sexual with, to step into this realm with.

If you are like, “I hated that joke Sean made about STIs, it felt ignorant given that 1 in 2 people gets an STI before 25, so it’s likely that felt damaging to some people at the table there,” and your partner is like “Haha you’re too sensitive, STIs are disgusting and only dirty slutbags get them,” isn’t that a wonderful opportunity to reconsider an intimate relationship with this person! It’s potentially likely that you might do better with a partner with, I don’t know… empathy?

Now, if your partner instead chooses to say, “Hmm, you’re right! I’ve heard that statistic before, though I haven’t given it enough thought. I imagine someone sitting there might have felt some stigma at that remark.” That’s more of one of those green flags we are looking for in a partner, and a sign that your intimate personal information might be treated with some more care.

It’s likely that you disclosing would be best in a private, intimate setting, or as a part of a larger conversation you all may have been having. Not on a dating app, not when you’re shouting over a metal band, not when someone if halfway into getting a boner or whatever. That is, if you have enough control over the situation to plan it (some folks aren’t so lucky).

Avoid: Self-deprecation (“I’m disgusting now”), speaking for the other person (“You’re probably going to hate this”), long intros (“We need to talk,” “I’ve been worrying about this for weeks and I’m petrified and I hate this right now and I have been panicking about your reaction and…”), weird manipulation stuff (“Everyone has left me when I said this but I know you won’t”), yadda yadda.

Could be helpful: Information (herpes is common, infection stats, how it’s transmitted), testing (you can get tested as it’s possible you have it and that might change our risk), your means to control it (I take medication, don’t have sex during outbreaks which are this often for me, we can use condoms and the risk is around XX%), time (“You don’t have to decide right now to have sex with me or not, do some thinking and reflecting and research and let me know when you’ve decided”), personal preference (“Please don’t tell anyone outside of your doctor about this if possible, it is very personal for me and I am trusting you with this information”), acceptance (“It’s ok if you make a decision either way/no pressure”).

“What if they take it poorly?”

Yup, it happens, although, not as often as folks fear. Understanding that people that live in this culture just don’t have access to affirming sex education, health information, and especially sexuality information is damaging to a person’s prospects (with or without an HSV diagnosis, honestly). That said, it’s important to remember that a person’s rejection is more based on societally programmed stigmas and fears than around your worth and value as a person (after all, you were likely nearing sex with that person, and they deemed you to be attractive and desirable before). They are not rejecting you (no matter the colorful words they might unfortunately use), they are rejecting the virus and their fear of it.

For further reading, Terri Warren discusses everything, including many common communication woes in her helpful handbook which you can find here. She also wrote a phenomenal book for those who are looking for a hard copy or a tangible item to read, markup, or share.

Your life is not over. Your sex life is not over.

Look to the future

In conclusion to this hefty piece, there is hope for a life to be lived after an HSV diagnosis. HSV is manageable, treatable, and not life-shortening. It’s annoying, stressful, depressing, and fear-producing, but a full life can be lived with a diagnosis. It can take time to come around to, but you are worth more than your HSV diagnosis. You will continue to live life, you will continue to love and be loved, and you will almost certainly have some bangin’ sex (if you need more help, talk to me). Medications to manage HSV are constantly being developed and tested, and vaccines for prevention and treatment are very close on the horizon. For now, the main concern of HSV is with its stigma in society. I, and others, and potentially you, are working toward destigmatizing sex and sexuality and many related topics, including HSV status. There’s hope out there. Let’s keep walking toward it.

Resources

www.reddit.com/r/herpescureresearch

https://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfact-herpes-detailed.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herpes_simplex_virus

https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/report/herpes-simplex

https://www.houseofminezine.com/shop/this-book-has-herpes