I recently had the fortune to pick up a book on Polyvagal Theory by Deb Dana and Stephen Porges, pioneering researchers in their field of neurobiology, neuroscience, and social work.

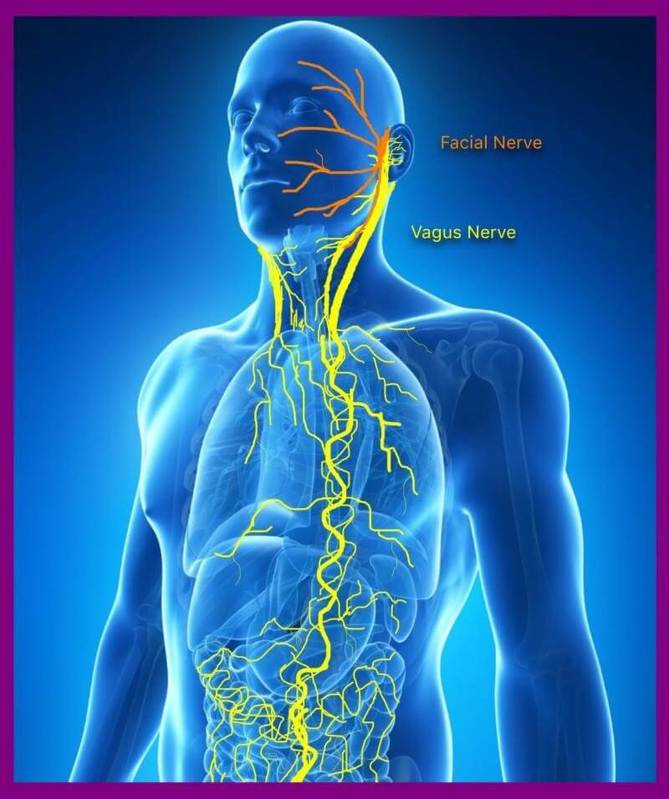

Polyvagal theory is a developing area of psychology that seeks to understand the connections between the vagus nerve and the body and brain. Scientists continue to uncover connections between the brain and body that help to inform various areas of work, therapy and mental health being one of them. One such connection is through the autonomic nervous system, of which the vagus nerve is an integral part, known to play a role in the brain’s connection with the heart, lungs, and digestive system. The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve and the longest nerve in the autonomic nervous system, arching down from the medulla oblongata of the brain into the neck, chest, and abdomen, reaching all the way down to the colon.

Polyvagal theory puts forth the assertion that vagal nerve stimulation and activation play a large part in regulating human bodily systems and functions as well as mood. Indeed, connections of the vagal nerve to mental health have been studied; vagal nerve stimulation has been used to treat abnormal heart rhythms, seizures, and treatment-resistant depression, among other things.

Dana and Porges assert that across the span of evolutionary history, phylogenetic adaptations have occurred over time as humans ascended from more primitive classes of beings: as mammals came about, and eventually humans, evolutionary adaptations occurred to the autonomic nervous system leading to the bodily processes we study today.

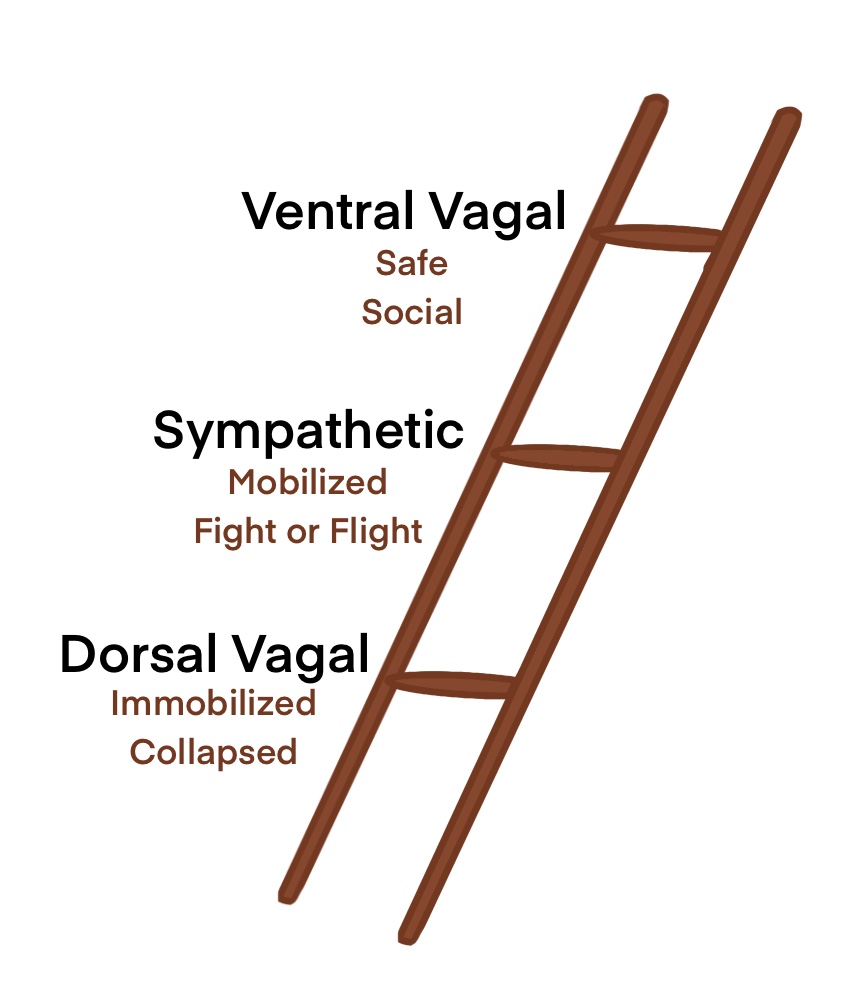

That said, Dana and Porges classify different anatomical structures associated with the vagus nerve with differing stress responses in humans. The more primitive vagus nerve portion, the dorsal branch, is said to elicit immobilization and dissociative reactions, akin to the “freeze” reaction. The more evolved sympathetic nervous system response represents our “fight or flight” reaction that occurs in the face of stress, uncertainty, or danger. And, the higher-level ventral vagus nerve activation is said to be associated with states of safety, community connection, and vulnerability. They liken these responses to a ladder, explaining movement up and down the ladder as failures to attain higher levels or feelings of safety leave one to slide down the ladder’s responses, whereas mobilization and safety allows one to seek a “higher” state of being.

The authors describe this dance (which more often feels like a tug-of-war) as one from connection to protection, and I strongly support this nonjudgmental wording of a very important process: humans wish to connect with others, it’s in our nature. But sometimes the need to protect oneself supercedes that. It’s absolutely understandable and well-intentioned, but like most best-laid plans, often goes awry.

To recap:

The Ventral Vagal system is the higher-order system that can only be reached in the absence of dangerous stimuli or perceived danger. In this state, one may relax, access higher level tasks like meditation and socialization, and feel connected to others.

The Sympathetic Response occurs in the presence of stress. Dana and Porges purport that through neuroception, an unconscious process, the body is constantly analyzing environmental stimuli to make determinations on safety and wellbeing, and may then activate a short-term stress response to increase survival odds. Folks enduring a sympathetic nervous system response may feel a jolt of energy, increased heart rate, jitters, and racing thoughts, among other outcomes.

The Dorsal Vagal system is the body’s last resort to stress and danger, wherein the person experiencing it may undergo an experience of “collapse” — systems shut down including slowed blood flow to cognitive areas of the brain, allowing protection from psychological or physical experiences of pain. People in this state may experience “leaving” or dissociative symptoms geared at protecting them from harm. They have trouble focusing on or attending to extraneous stimuli. They may feel frozen, numb, or out of control.

The implications of the study of polyvagal theory are far and wide for our understanding of psychology and therapy. Put simply, the ability to associate one’s state of being with a biological system or function may help to absolve the observer of any associated guilt or shame around emotional reactions that may be hurting or hindering their progress. Moreover, to develop further insight into such processes can allow one to gain more control over their movement through the various states associated with vagus nerve activation.

Understanding this theory may also help outside observers and peers to recognize the importance of creating safe environments for trauma survivors to flourish; knowing that people may literally not have the biological ability to attend when in the presence of a dreaded or stressful stimuli, for example, may help to decrease conflict or hurt emotional feelings in a couple’s setting. Whatever the case, creating more space between biological functions and our following understanding of them (or “storying,” as the authors suggest, our cognitive ability to tell stories about events follows our neuroception of them) allows persons to develop insight and control over their own mental and physical health and wellbeing.

The proposed solutions that the authors suggest are first to understand the different aspects and associations with different vagus nerve states. In doing so, they suggest the tasks of mapping your emotional states in line with the proposed frameworks over a series of three exercises, asking qualitative and non-judgemental questions along the way. They suggest continuing to develop compassion (as opposed to criticism) for oneself through respect for autonomic bodily systems and the ability to create further insight through tracking of these systems. Finally, calling one’s attention to moment-to-moment changes in their state suggests the importance of mindfulness exercises, with the ultimate goal of connection with others as opposed to reliance on protective mechanisms. The ability to build trust in oneself and others is inexplicably important for our self-realization as social creatures.

1 Reply to “Polyvagal Theory – Stress, Trauma, and Enlightenment”

Comments are closed.