We hear this word all the time.

“I’m so stressed out.”

“I’m just going through some stress right now.”

Gosh, even my houseplants get stressed. (I’m trying, OK??!)

And values around it. Stress is bad, stress is normal, stress is necessary, stress is inevitable.

I’m here to say, well, yes, stress is inevitable. It’s common. We go through life, something less-than-wholesome happens, and we have a physiological response to those stimuli. Boom, stress.

Call it your fight or flight response, or if you want to get fancy, let’s call it activation of your sympathetic nervous system, either way, it’s all the same: the body notices something, we have an emotional reaction, then there’s a reaction in the body. Makes sense, right?

However, in the course of my work, I’ve come to be familiar with what’s known as acute stress versus chronic stress.

Acute stress is pretty straightforward. Let’s hearken back to the prototypical fight-or-flight example. There’s a stimuli. Let’s say caveman us sees a tiger while we’re out on our berry run. We have an immediate, powerful bodily reaction: the “oh shit” moment.

You know what it feels like. The stomach dropping out, heart pounding, can’t-breathe kick in the pants that makes you jump into action: You can choose, in a split second, to fight, or flee. (Or other cute reactions like freezing or fawning but we can get to those later.) Then, you escape. The stressor isn’t present; it’s over. Things go back to normal.

Acute stress is helpful, in a way. (More helpful when dealing with an imminent threat, but hey. Modern society and all that. The brain can’t tell what is a tiger and what is asking out a hot person at the bar, it’s all horrifying. Have you ever heard something more poetic?) Say I have to give a speech and I’m sweating and feel horrible. This will pass, but maybe it motivates me to do my best and not mess up. I have a test tomorrow and I can’t sleep. OK, perhaps this means I will study more and review stuff so I can be prepared. It feels crummy, but then it passes.

Chronic stress is more insidious. Sometimes there are stressors that don’t go away. My bills and taxes don’t go away: I certainly can’t fight my tax person, and I can’t run away. I kind of just have to go through it and manage it, sometimes every day. What stresses one person out may not affect another the same. Even so, sometimes we are exposed to stressors that linger: a relationship, a workplace, health troubles, natural disasters, politics, you name it.

When chronic stress occurs on the body, the fight or flight response happens, and keeps happening, and the body does not get a chance to return to the normal resting state (call it rest and digest or the parasympathetic nervous system response). A longstanding chronic stress response has an adverse effect on multiple levels of functioning in the body.

OK, let’s check out where the stress response originates.

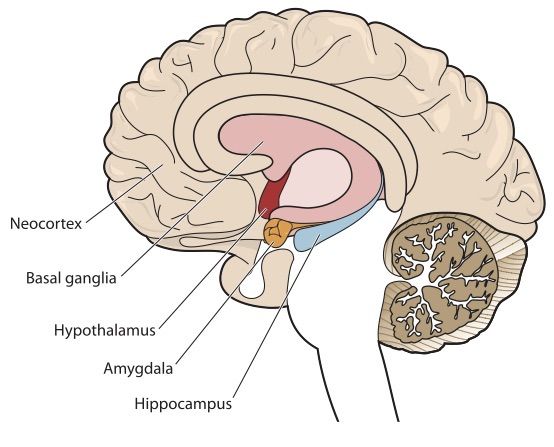

So, something stressful happens. We hear a partner call us a name, we think about that one time we tripped down the stairs, we see a tiger, whatever. This information comes into the brain and then gets routed through the amygdala, where we experience an emotional response. “I’m hurt they called me that,” “Oof, that really hurt, what a mess that all was,” “Oh shit is that a TIGER??” Hurt, grief, fear, anger, etc. This results in a cascade of reactions down what is known as the HPA Axis, activating the sympathetic nervous system response.

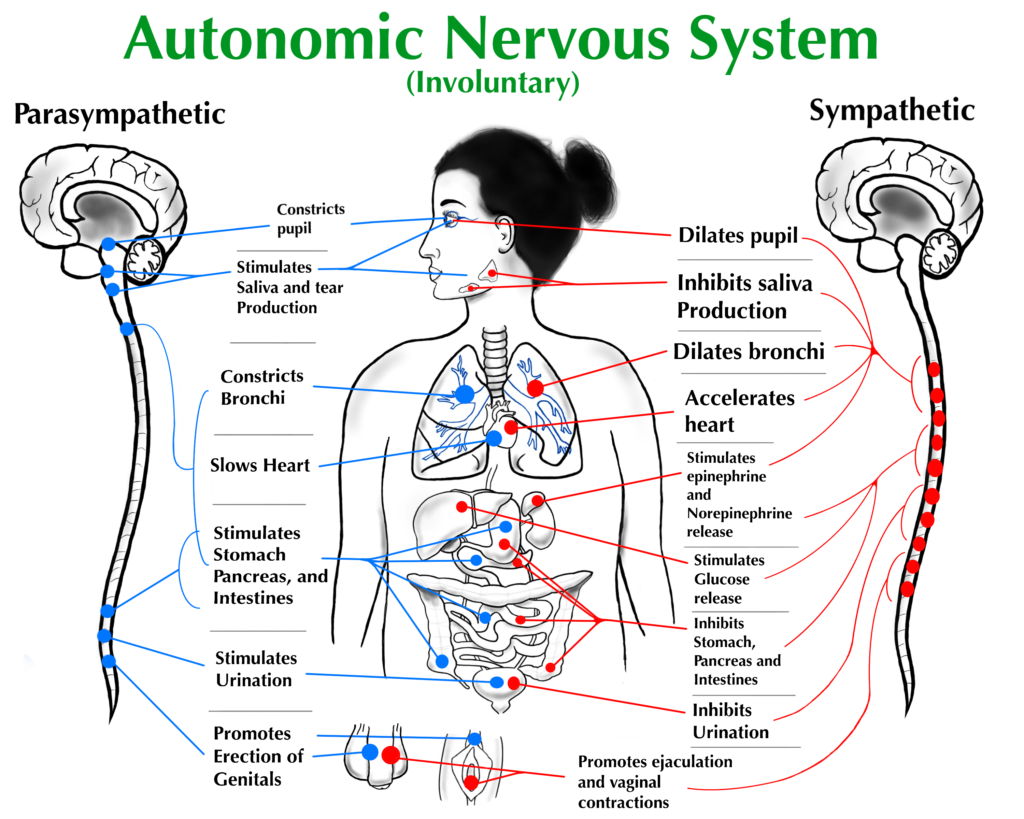

This image shows the consequences of the sympathetic nervous system response (the stress response) on the right.

OK, let’s go down the list here. But, let’s think about these bodily changes as in a very human emergency: to preserve the necessary functions of life (mainly, being alive, so not being around the tiger), the body almost goes to a shutdown mode, let’s say, like accessory lighting when the power goes out: the store shuts its lights to save the scarce energy to keep the freezers running. The body chooses certain functions to prioritize and others to shelve as it fights for its life.

- Pupils dilate. This happens to let more light into your eyes so you can have the best vision possible for a temporary period of time, to make better decisions about fighting or fleeing, or take in more information about the environment so you can be the most safe. The downsides: tunnel vision, blurred vision, dizziness, headaches.

- Saliva production is inhibited. This makes sense as the body prioritizes survival over digestion (you’ll see more of this in a bit). The downsides: dry mouth, frog-in-throat feeling, thirst, trouble speaking.

- Bronchi dilate. The body wants to quickly take many short, shallow breaths to quickly oxygenate the muscles so we can engage in conflict or run away. The downsides: feeling like you can’t breathe, chest tightness, not being able to catch a full breath.

- Heartbeat accelerates. Your body wants to get that blood pumping! It takes effort to send more blood to the muscles and extremities. The downsides: the feeling of a racing heart, chest tightness, high blood pressure, strain on the cardiovascular system.

- Adrenaline release from the adrenal glands above the kidneys. Adrenaline kickstarts your system and is a hormone responsible for many of the bodily functioning changes here we are discussing. The downsides: that “stressed out,” “keyed up,” or “on edge” feeling, anxiety, shaking, cortisol production.

- Glucose is released. Sympathetic response changes the body’s prioritization of digestion, and the body uss glucose as energy to power muscles and other cells responsible for keeping us safe when the MO is to fight or flee. The downsides: this process is managed by a stress hormone called cortisol. While this process is occurring, the immune system becomes suppressed, which makes us more likely to become sick when chronically stressed.Cortisol also increases the likelihood of storing abdominal fat — if the brain fears stress, it’s going to save up for a rainy day. Finally cortisol plays a role in sleep/waking cycles, so chronic stress may affect your ability to get a restful sleep.

- Peristalsis is inhibited. The smooth muscle movements that enable us to digest are deprioritized in favor of setting up other muscles for success. The downsides: chronic stress is implicated in GI distress such as ulcers, diarrhea, constipation, IBS and Crohn’s disease flare-ups.

- Urination is inhibited. Another example of a bodily process put on hold. The downsides: stress can contribute to an overactive or underactive bladder and cause your brain and body to misinterpret signals about frequency and urgency of urination.

- Sexual side effects abound. You didn’t think we could get through this without talking about sex, I hope. Stress has a myriad of effects on the body’s sexual functions, but in keeping with tradition, when the body is in fight or flight and is just trying to stay alive for a little bit longer, it’s generally going to deprioritize reproduction. Some stress is good for sex — think the titillating, heavy breathing, excitement of passion; this is the sympathetic nervous system activation we want. NOT “Oh God I have to pay my taxes and it’s all I can think about.” The downsides: not feeling desire or arousal, inability to orgasm, erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, tightening of vaginal muscles, sexual pain.

Also, stress and adrenaline cause blood vessels in skeletal muscles to dilate. Makes sense given what we’ve just discussed, right? But, chronic muscle tension can lead to increased instances in chronic pain, as muscles tense, tighten, and shorten, and this can cause muscle weakness, increased instances of muscle tightness, potentially leading to pinched nerves, headaches and migraines.

Again, it makes sense for the body to enact these dramatic changes when it’s fighting or running from a tiger. But the body can’t tell the difference between a tiger and your job interview tomorrow, they all activate the amygdala the same. Fear. Stress.

So, what does this mean? Yes, Sara, I know it’s bad for my body (thanks for giving me something else to stress about). I know, you can’t just shut it off.

As a first step, increasing your consciousness of your body’s processes are good. It’s good to be able to know when your body is having a stress reaction. It’s progress to feel the ol’ ticker pounding and be like, “Whelp, there’s that darn tootin’ stress again.” (Sorry about that.) But really, having insight into it is part of the battle already won. Now that we know it’s stress, we can find ways to manage it. Maybe if we know it’s stress and not just, “Well that’s life, to feel crappy all the time,” we can notice that sometimes we have control over our environments and can change our exposure to certain stressors. Say, avoiding that mother-in-law. Or, beginning the process to consider a new career field. Or changing that group of friends.

Knowing it’s stress means we can focus in on our stress-busting toolkit. Here’s some suggestions —

- Therapy. Self explanatory, in a way, because you’re on my page. But hey, who knows. Sometimes just talking about stuff can bring about a feeling known as catharsis. Sometimes stress can be worsened by the way we think about things, so we can explore thought structures and change bad brain habits. Sometimes having someone to talk to who’s on your team can be helpful and comforting.

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Hey, it’s in the name! Who knew. Engaging in meditation, or bodily exercises like yoga, or trying techniques like EFT/tapping help the body to re-enter that parasympathetic/resting state. If you don’t know where to begin, ask me. You can also check out resources like the apps Calm or Headspace, or by trying YouTube Channels like Yoga With Adriene or Brad Yates.

- Sleep Hygiene. Sleep is the foundation for whole body health. Practicing good sleep hygiene can mean — reducing blue light exposure (screens) an hour before bedtime; going to bed and waking up at similar times during the week; not eating or drinking or exercising an hour before sleep; establishing a nighttime routine or ritual that you repeat daily; using your bed just for sleeping and sex; etc.

- Exercise. I know, this is a tough one. But studies consistently show that just having 30 minutes of low-impact exercise daily (do I hear “walking,” folks?) can have crazy benefits as far as boosting mood and increasing cardiovascular health (which, remember, takes a hit from that stress response). It can be a nature walk. It can be a walk around the block. It can be some gentle movement or yoga at home. It can be climbing a mountain, I don’t know, let’s get creative! But moving that body will feel good, allow you to have some “me time,” and be mindful in your body while doing it (even if you end up bright red like this girl over here).

- Leaning on Social Supports. You have friends, family, peers, colleagues, and loved ones who can help to shoulder emotional trials and tribulations alongside you. If you don’t, and if you’re open to hearing me say it for the hundredth time, you can have this, too, and we can figure out ways for you to meet the right people because you are loveable.