How about we take a nostalgic trip down memory lane to the 90s (and early 00s, if we’re being honest). A time of Tamagotchis, frosted tips, pogs, and the oh-so-hyped “Rachel” haircut. But let’s not forget the less-than-glamorous side of 90s culture – a time where body shaming and diet culture were all too common. 90s culture may have been rad in some ways, but it also left us with some serious scars and shit to unpack. This one’s for you, if your birth year has an 8 or 9 in the tens place. So grab your favorite oversized flannel shirt, and prepare for a deep-dive into the dark side of our millennial childhoods.

Body Image

The impacts that current culture and the media had on body image in this fabled time were of huge importance.

ALERT & trigger warning for those who have body image “stuff” (myself included), I’m going to include images and media from the times that might still prove to be triggering for you. So, skip this section (or maybe this whole damn article) if you have to, because sometimes forgetting this shit might be for the best. I know I wish I could.

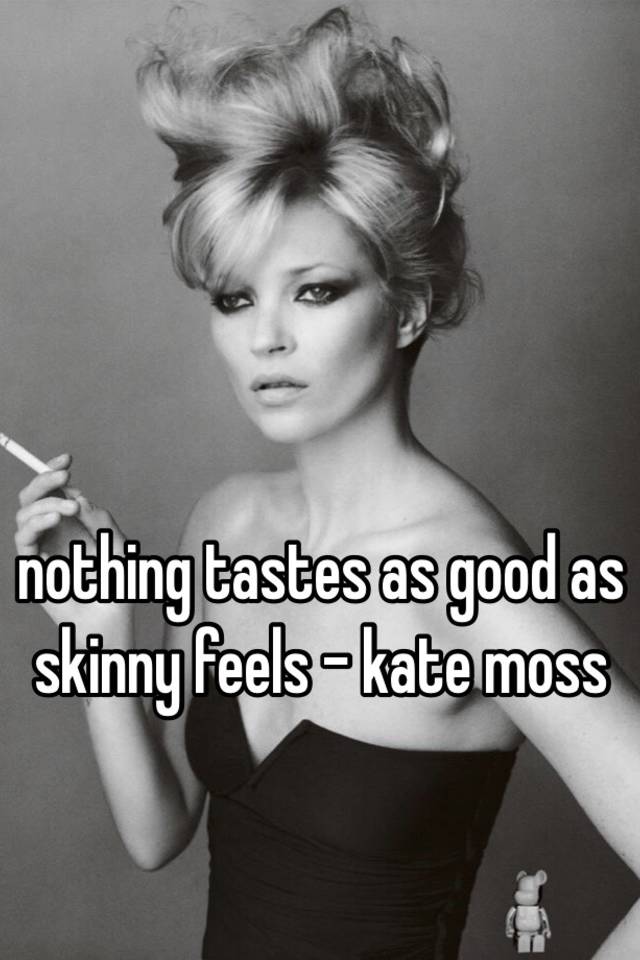

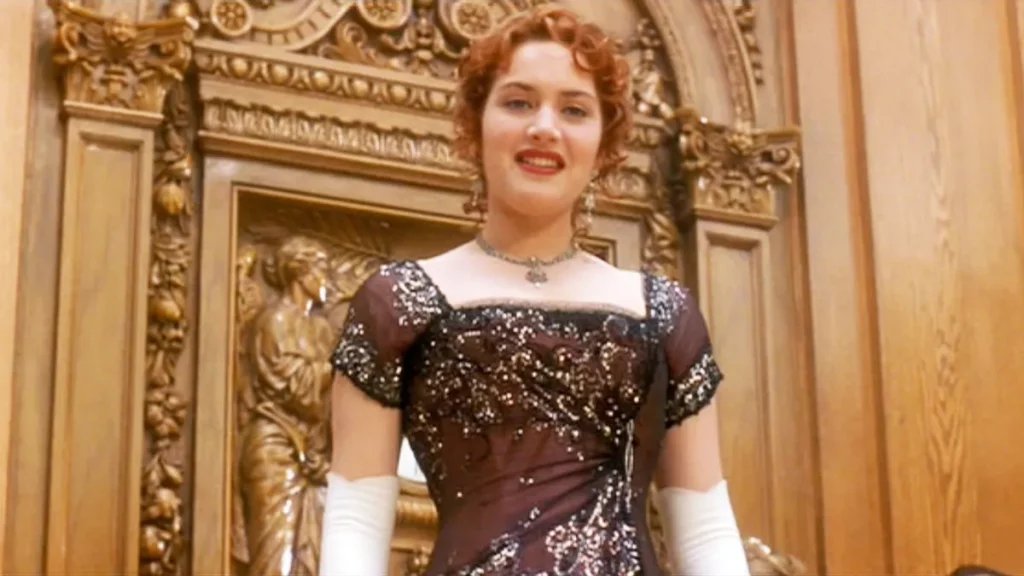

The 90s (and again, early 00s) was an era of supermodels and waif-thin beauty standards, affectionately known as “heroin chic.” While low-rise jeans were looking hot on some and “does this make my butt look big” was encouraging laughs across the country, the rest of us were suffering (and YES, to my gen z and alpha homies, can you believe having an ass was seen as BAD). The 90s created a culture of thinness, where anything above a size zero was seen as “fat.” That sh*t sticks with us, even today. From unrealistic body standards in the media to the constant pressure to “get that beach body,” the 90s culture of body image still haunts us. From Kate Moss strutting down the runway to the posters of Calvin Klein ad campaigns gracing our bedroom walls, we were bombarded with images of “perfection.” And let’s not forget the constant obsession with being “size zero” and those impossible “six-pack abs.” Yeah, it’s no wonder body image issues were, and still are, a common struggle for many of us who were born or grew up in the 90s.

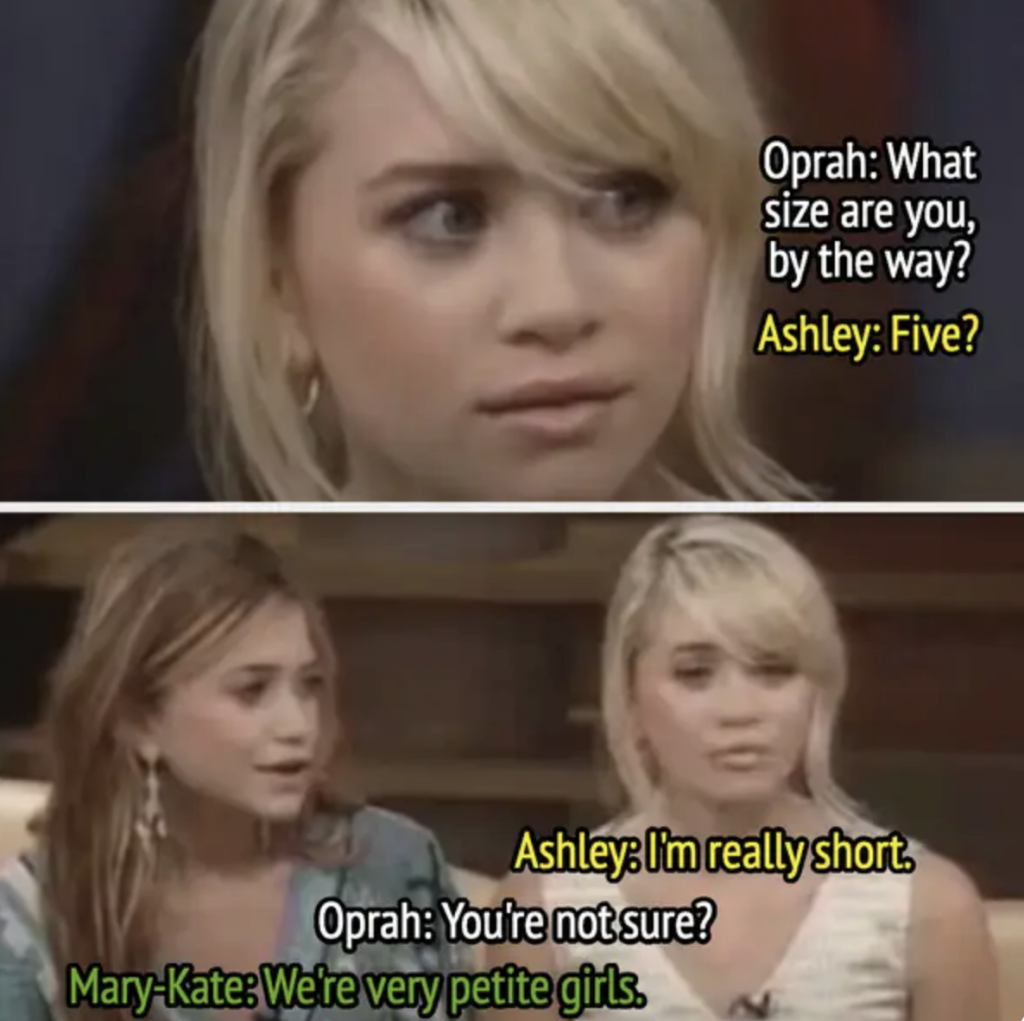

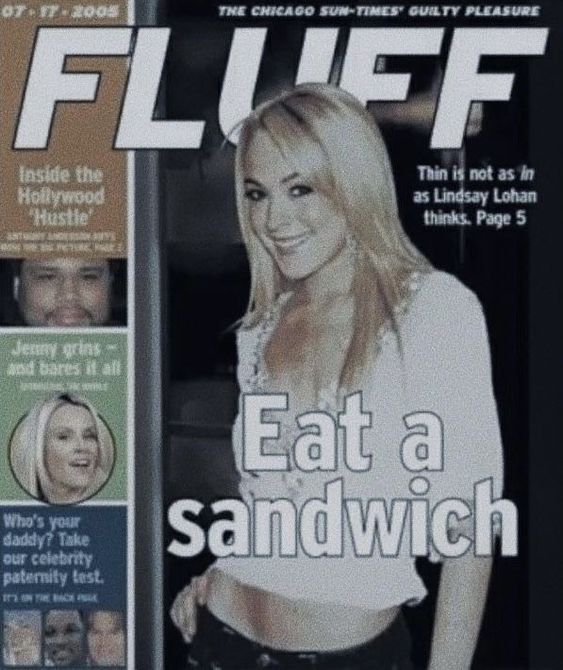

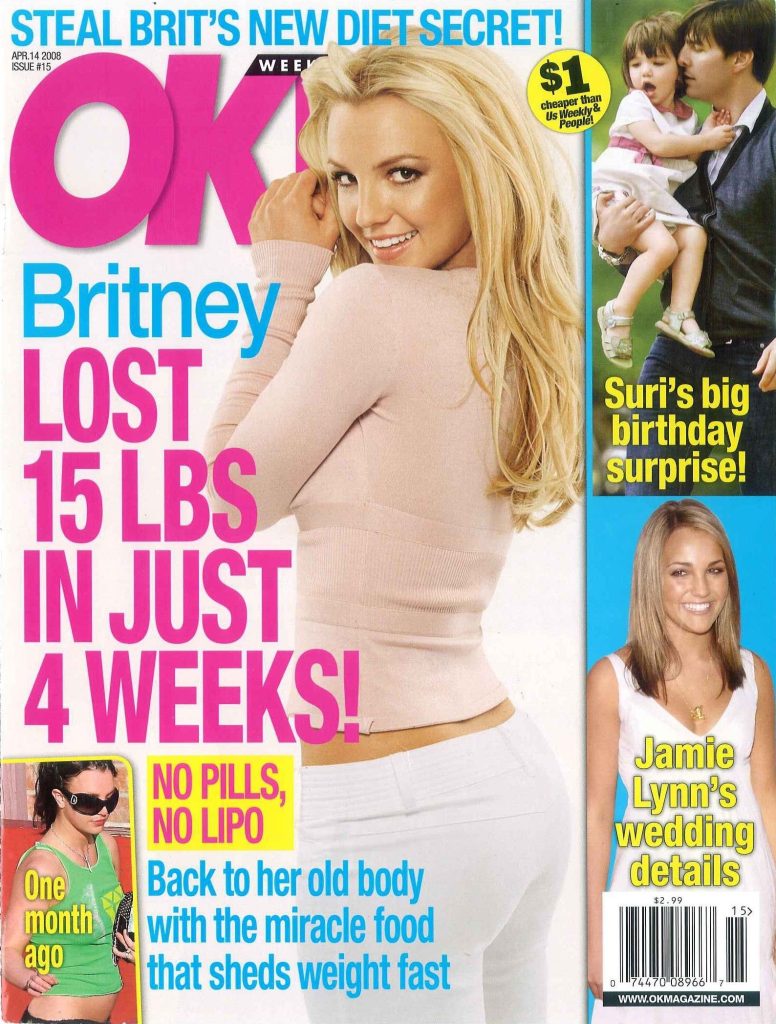

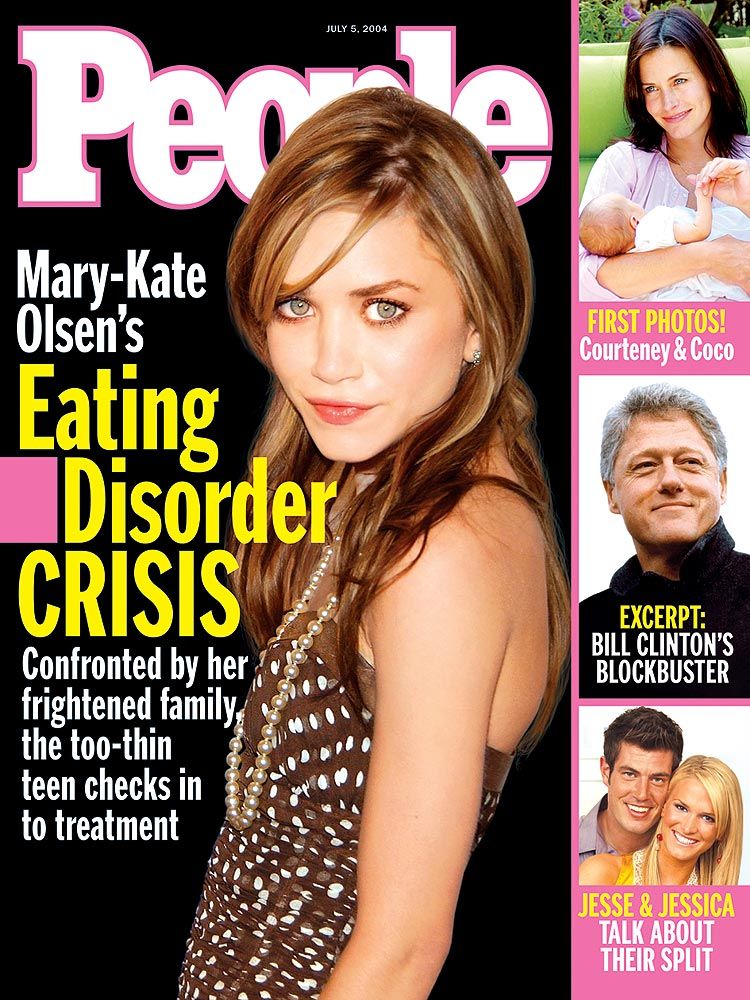

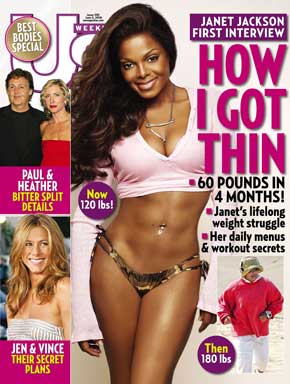

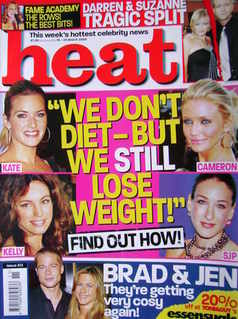

I remember growing up seeing airbrushed and retouched images of women and thinking that was normal, not only the ideal to aspire to but that’s just what folks looked like, therefore that I, in all my imperfections, was ugly. I saw these reminders every time I was in a grocery store aisle, every time the TV was on, every time I saw a billboard, every time I got a magazine. (I can’t even imagine growing up with a smartphone now). People made cutting, heinous remarks about folks’ bodies and weights in a way that is known to be damaging now, without a care or second thought.

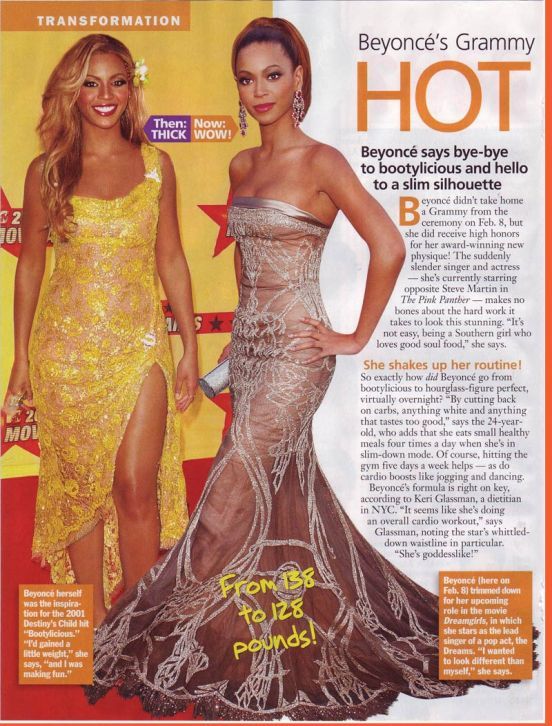

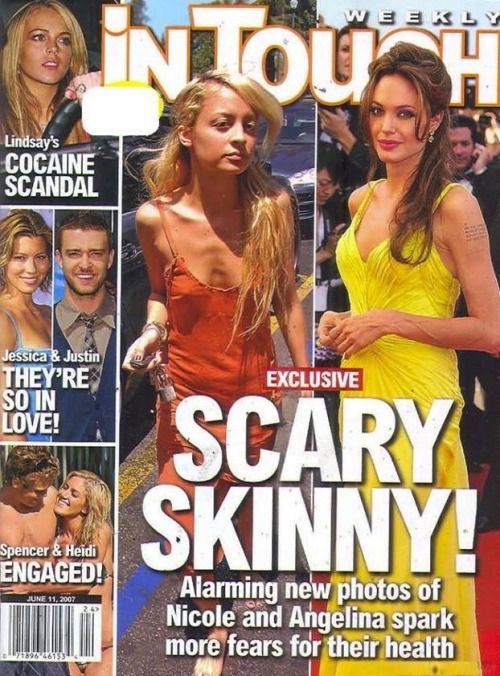

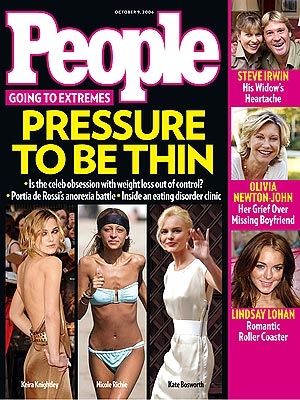

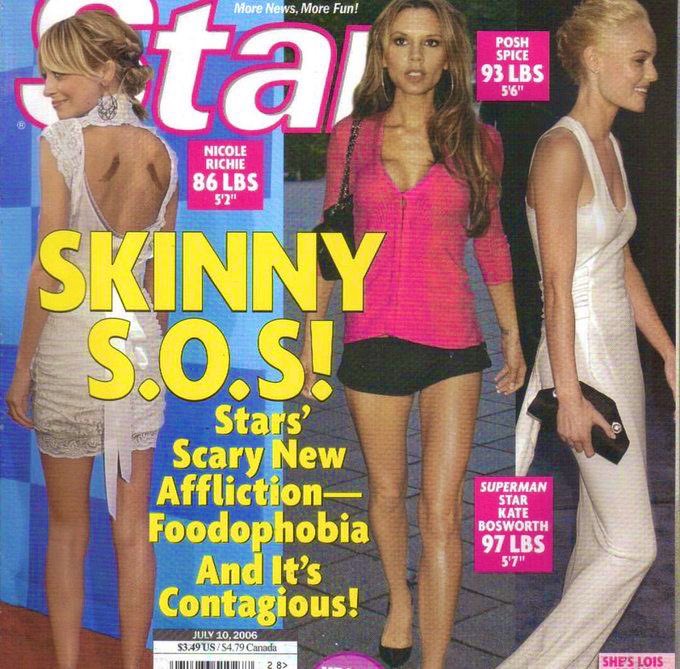

Women were mocked, women’s bodies were posted on the front page of tabloids criticizing their stretch marks or bad plastic surgery or positing about possible pregnancies or surgeries, women were made fun of for being flat-chested and forced into implants — every single piece of media criticized women’s bodies so blatantly that I cannot imagine how terrible it was to be famous at that time.

I grew up with a 90s mom who subscribed to terrible diet culture fads, especially when the words “low fat” and “carbohydrate” entered the common lexicon. I remember hearing Kate Moss say “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels” and trying to adopt that as life advice, restricting my food intake to literally nothing on days where I felt “fat.”

I remember learning to join in when conversations or tabloids criticized famous women’s bodies; I felt nudged into feeling absolutely certain these women were “letting themselves go,” and at that time it felt like the only way to avoid being under the microscope was to join the scoffing crowd.

By being a jeering onlooker, one escaped the ravages of being under scrutiny. I truly think that’s what informed many of the body-negative speakers I was exposed to, my mother included. By pointing a finger, the person doing so would temporarily avoid criticism thrown their way. And, there was a LOT of criticism flowing in those times.

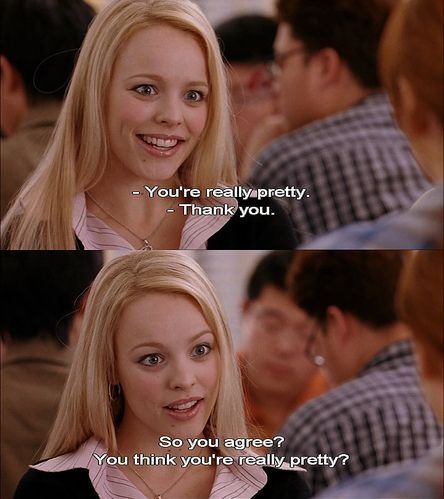

This same trend can apply to criticism about the self, too. It makes me think of the quip in Bo Burnham’s reaction video skit; “…honestly it’s a defense mechanism… I am so worried that criticism will be levied against me, that I levy it against myself before anyone else can.” Check it out in this appropriate-era clip from best-movie-ever Mean Girls —

So, no one at this time was really modeling how to talk about the self or others positively. We learned to pick and prod, to neg and criticize and tear down. This behavior persists today, of course, but I want to pay particular attention to folks who came of age in this particularly fucking negative era, because it’s close to my heart. We didn’t want to say anything good about ourselves because —

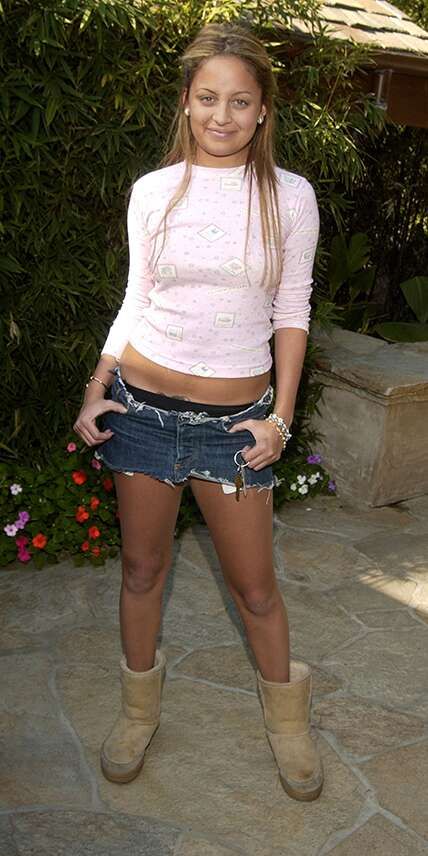

One of the major points of criticism that was levied at this point was about body weight, and “fat” was the major insult of the era. Women were picked apart for having a body that did not fit into the current trend of BODY FAT PERCENTAGE, or APPROPRIATE PLACES TO HAVE FAT (which, guess fucking what, are nearly impossible to control, but I digress).

Here’s an image gallery of famous women that this era declared to be “too fat” —

Christina Ricci (Photo by Jim Smeal/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

(EXCLUSIVE, Premium Rates Apply) Nicole Richie (Photo by Amy Graves/WireImage)

Do you think any of those women were fat??

I look back on these photos and feel disbelief, certain of our collective brainwashing by a culture set on cutting down women; pitting women against one another was just one way they accomplished this (harken back to Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me,” the vibes being “I’m not like her, I demand you pick me”).

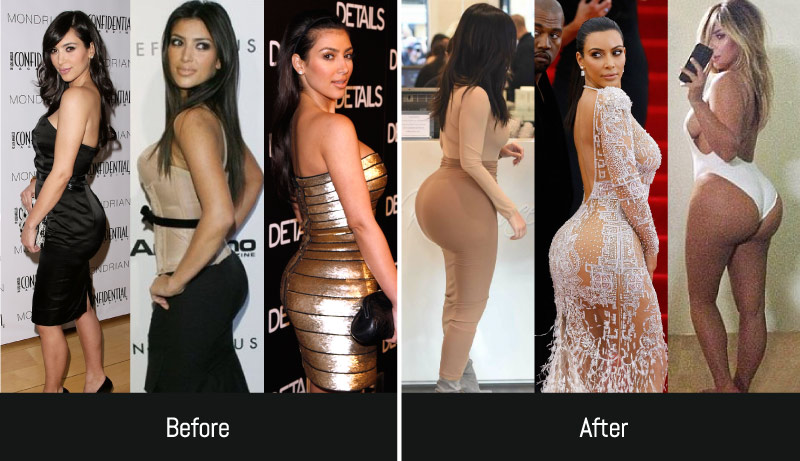

As I get older, the perspective I gain is that society treats bodies (particularly, in this case, women’s bodies) as commodities whose “value” changes over time in line with different social trends of acceptability, attractiveness, and attainability. How fucking absolutely ridiculous is this shit, and yet, it’s the world we live in.

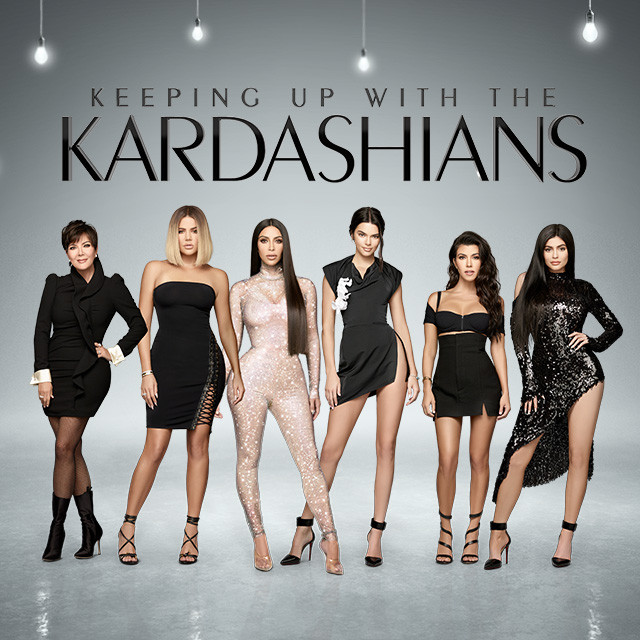

Soon after the 90s and 00s, a time was ushered in where women’s bodies HAD to be thin still, but with fat on the chest, ass, and thighs. An entire new trend of bodies was ushered in by the growing fame of the Kardashian family, and suddenly the flat asses of the 90s were “out of style.” Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass” proudly blasted on pop radios everywhere, instead shaming women who couldn’t grow an ass, with the intention of lifting up fellow booty-havers. Folks who were getting crushed under thin-centric trends, despite their approval or otherwise for this family, breathed a collective sigh of relief as their jean waistbands trended higher.

All of this begs the question, how do entire groups of people, or a body’s inherent manner of storing fat count as a “style???” I am so angered by all of this, and yet, I appreciate the level of distance afforded to me by this anger, in that my “need” to conform to body trends is much reduced. Although growing up in the 90s and 00s gave me a dysmorphic view of my body and disordered eating, the ability I have now in my 30s to understand what this did to me has allowed me to be a more kind, accepting, and caring person toward my own body and psyche, and to others’.

So, understanding body image stuff matters. Not only for the above, but ALSO, because understanding that society treats bodies as commodities means that what’s “acceptable” is constantly in flux. And, the 90s are having a revival, baby. Have you seen the mullets, fanny packs, and giant jeans? Trends get recycled. And thinness is again becoming “the norm” over curvy bodies, as hundreds of celebrities showing off their weight loss after ozempic are now trending. Buckle up, friends. Low-rise jeans, I’ll see you in hell.

Diet Culture

Not much more needs to elaborate on the above: growing up in the 90s and 00s was hell on the body image (as it was prior and after this time, as well, of course). Along this same vein, the 90s and early 00s ushered in many new diet trends and fads, as scientists were still trying to understand that human bodies do, in fact, need nourishment.

“Diet culture” here refers to the trend of society to reward folks for being thin, punish folks for being “too fat,” and thereby incentivize people to need to always be “working” to be thinner, thinner, thinner. Not dieting (trying to lose weight) was “dangerous,” because people could be complacent and that was the first step toward “letting yourself go.” This just created a culture where no one was ever “good enough,” and everyone was on a slippery-slope brink of becoming fat AKA worthless and bad. So people could never relax or be anything other than anxious, and many who grew up in this time carried this with them throughout their lives until it could be unlearned.

Diet culture was thriving in the 90s, with every magazine cover reminding us that we needed to be thinner, lighter, and smaller to be considered beautiful. From the allure of weight loss pills to the obsession with calorie counting, we were constantly bombarded with shaming messages about our bodies. And let’s not forget the fucking ridiculous “thigh gap” trend that made us question our worth based on the width of our damn thighs. The “thin is in” mentality meant that women (and men) were constantly told to restrict their food intake, to the point of obsession. The 90s glorified diets, weight loss pills, and fat-phobia, leading to a generation of people with distorted views of their bodies and a toxic relationship with food. Criticizing fatness was made into entertainment and faux health-consciousness.

I learned rules about “good foods” and “bad foods,” foods to avoid and foods to punish myself for eating. I learned about diets, and “cheat days,” and the victory of claiming “I was good today!” vs the crushing self-judgment of, or the devious silliness of “I was bad today.”

I learned from a young age to suck in my stomach constantly, which led to chronic muscle tension and pelvic floor issues among other things. I learned to notice what my stomach felt like against my clothes, constantly monitor this feeling, and hate it, flinching when others would touch me because I had to conceal my bulk. I remember feeling like I was fat when I was age 7 at the earliest, and learned to handle this feeling by overexercising and following strict and stringent diets.

The first diet I can remember being implemented by my parents was called “The Soup Diet,” and this was then followed by “The Atkins Diet,” counterbalanced with a learned need to obsessively count and track calories.

This implanted in me a need to be ever-vigilant, lest I end up “in trouble.” This cemented food and weight as ideas so centric in my mind, that I literally couldn’t conceive the possibility that others could have a healthy relationship with food and eating; it just felt like everyone was faking it. I now recognize this as the cognitive distortions of a mind with a disordered relationship with food, dieting, and body image.

When looking back, I’m not really sure WHY we thought this trend of constant dieting existed, if we’re being honest — at that time it wasn’t really about being healthy. It was more about avoiding shame and criticism, which was much more acceptable at that time, and trying to have a desirable body for our male-gaze centric society.

Really, though, let’s be honest — it’s about capitalism. Our capitalistic society requires that people never be happy, and always be grinding to the next thing so that they can always be SPENDING MONEY on “cures” and “fixes.” The diet industry is a $76 billion a year industry. And make no mistake: this didn’t end with the advent of big booties in the teens, it just adapted.

So what do we do with all this?

I’ve been on both sides of the coin. I’ve had a massively disordered relationship with food and eating and can see this as the result of growing up in a culture that treated bodies and weight in a completely unacceptable manner. I “knew” I was fat and ugly while I was still in elementary school, and grew up under role models who complained about their bodies and weight, never seeing it modeled for me that someone could like their body or admire it without being at risk of being ridiculed or sliding into “unacceptable” territory.

And now, in my 30s, I can say I have largely deprogrammed a lot of that “learning,” and can see myself through a more realistic and less dysmorphic critical lens, and haven’t read a nutrition label or counted a calorie in nearly a decade (and am healthy and happy, imagine that!). So much less of my brain space is filled with these exhausting rules, and it’s fucking liberating.

Healing from the culture we grew up under regarding body image, whether it was growing up with corsets and rumps or tiktok and instagram, is 100% possible. A lot of the work we do on ourselves personally or in therapy is in unlearning old things that no longer serve us. I like to say, the first step is noticing something’s not right. If any of the above rings true for you, you’re doing it. Notice this stuff was given to you by our fucked up culture around bodies and food, and was not your sole creation.

We might notice stuff and then take the next step of asking, “Is this mine or was this given to me?” Noticing that something in your mind is not of your own creation is an important step in creating distance between you and it. By saying, “I hate that this time in my life taught me I’m not good enough,” it helps to separate us from the feeling of this as objective reality (ie “I am not good enough”). This distance is critical for healing as we work to unlearn negative habits and lessons and turn a kinder, more accepting look toward our own selves.

I understand that “body positivity” feels like a big step, particularly if you’ve been practicing body negativity so routinely that it feels like it’s objective fact. To those folks I suggest, why not first practice body neutrality. Perhaps we can just view our body as-is, and separate from it negative cognitions and thought distortions. We can then avoid the overly-saccharine and fake-feeling positive remarks too, and still move toward healing. This looks like —

“I hate the bump on the bridge of my nose” -> “I appreciate that my nose lets me smell stuff.”

“I don’t like my butt” -> “I can live with my butt as it is.”

“My thighs are too fat” -> “I appreciate that my body got me from point A to point B today.”

“My hair is ugly” -> “I can learn to like my hair.”

This may sound silly, but it’s one of many, many things I tried, that finally clicked for me. I began to love and appreciate my body more when I viewed it not as a millstone around my neck, not as an object to attract a partner (or the main reason I never might), not as a thing I have to “tame” or bring in line with societal standards, but as a flesh sack I inhabit that gets me from A to B. When I travel, spend time outside, hike, eat tasty local cuisines, get a massage, or appreciate resting my body, I feel what it’s like to see my body not as a commodity, but as a device that makes my life pleasurable, painful, and liveable all in one.

When we see our bodies through the lens of their abilities to give us physical experiences and sensations, we are more likely to find ourselves treating our bodies with more gratitude and objective neutrality, rather than when looking at bodies through the lens of seeing if it can fit into fucking low-rise jeans. And you’ll never see me wearing them again.

Further reading:

More Than A Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament

The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women

One Reply to “Y2K & Body Image”

Comments are closed.