Money is culturally constructed.

I know! It’s real, you can touch it, you can earn it, you can spend it, you and I know everyone wants it. All the same, in my work with folks and my journey with myself, money has some inherent, learned value that you cannot separate from it.

Maybe you’ve never made space to examine your feelings around so common an everyday object, but they’re there: otherwise money wouldn’t be a stressor for nearly everyone, or a common top reason for divorce, or something that you might disagree with family or friends on, if it was treated as neutrally as a pair of shoes or a houseplant.

Growing up, I learned money was something to be afraid of: I lived under a constant fear of my dad losing his job, had to wear my brother’s old clothes, and wasn’t allowed on school trips to other places that were deemed “too expensive.” I learned to never ask for money and that anything I wanted to do, or something I wanted to get, I had to buy for myself, so I got a job as soon as possible. I remember going to the store at a young age with a relative and feeling amazed when I pointed out something I liked and it was added to the cart without a struggle, only to be told later by my parents that that person was “bad with money,” the ultimate insult. Presents to mark occasions were often savings bonds, things I couldn’t touch until later. We went to buy a car after an accident and my father forbade me from disclosing this to anyone because “they’d treat you differently if they knew.” I was critiqued for every purchase I made through my first bank account that wasn’t absolutely necessary. And then came 2008; everything was doom and gloom — I was instructed to focus only in school on majors that would lead to a lucrative career, be damned what I liked or was interested in. I was told this message by parents, mentors, teachers, and peers, ad nauseum.

I can look back on this timeline and understand now only that these things I took as fact: saving money is most important, don’t ever spend money if you don’t need to, don’t ever be in a position where you owe money, never lend someone money, always balance your checkbook and bank account to the cent… you get the picture. These things I took as fact, as the “right” lessons, as “common sense” … they are just something I learned, something given to me, akin to a cultural value. Looking back now, I can understand that I had a solidly middle-class upbringing, but it made me to feel very afraid, nearly terrified, of “a rainy day,” whatever that meant.

America has been described as a meritocracy, meaning, if you work hard, you will be rewarded. There are so many wealthy, elite idols that are held up as role models, and people look at their intelligence, hard work, and grit as factors that contributed, or directly created, their success. The message makes sense, right? If you work hard, you will achieve success. What isn’t talked about is the flip side of the belief in meritocracy, the implication that, if you don’t achieve success, it is then because you have not been working hard enough.

As I grew up and learned more about culture existing in the world around me, my reflections on money had to factor in, because that discourse exists everywhere in America: persons categorized as low socio-economic status are disproportionately non-white. I was raised in a Republican, fiscally conservative bubble for a long period, where phrases like “get a job” or “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” were hurled around willy-nilly, as if it would be that easy for someone to climb out of poverty. The belief of meritocracy was ever-present: an Orwellian Boxer-like model was presented, the phrase “I will work harder” was treated as a rallying chant as opposed to an untenable death gasp.

Let me say it again, for myself and for you, if you can find familiarity here: this isn’t real. It’s just one way of looking at money, work, success, power, you name it.

I was raised in an American cultural context around money. Money somehow ruled the game, and I felt great fear around spending it, and coupled with a very American focus around accumulation of stuff, and status symbols, and “retail therapy,” it was all very confusing. It seems that accumulation of wealth is incredibly important to Americans, perhaps at the expense of other aspects of life. “Retirement” is a concept that’s thrown around, as though if you devote most of your life to busting your ass and saving money at the expense of your free time and leisure (hey, you might get 10 whole vacation days a year), that somehow you might be able to relax at age 67 (is that the age now?), if you make it that far.

A story I like to consider is the Parable of the Mexican Fisherman, a story adapted from the writings of Heinrich Böll, in 1963:

An American investment banker was taking a much-needed vacation in a small coastal Mexican village when a small boat with just one fisherman docked. The boat had several large, fresh fish in it.

The investment banker was impressed by the quality of the fish and asked the Mexican how long it took to catch them. The Mexican replied, “Only a little while.” The banker then asked why he didn’t stay out longer and catch more fish?

The Mexican fisherman replied he had enough to support his family’s immediate needs.

The American then asked “But what do you do with the rest of your time?”

The Mexican fisherman replied, “I sleep late, fish a little, play with my children, take siesta with my wife, stroll into the village each evening where I sip wine and play guitar with my amigos: I have a full and busy life, señor.”

The investment banker scoffed, “I am an Ivy League MBA, and I could help you. You could spend more time fishing and with the proceeds buy a bigger boat, and with the proceeds from the bigger boat you could buy several boats until eventually you would have a whole fleet of fishing boats. Instead of selling your catch to the middleman you could sell directly to the processor, eventually opening your own cannery. You could control the product, processing and distribution.”

Then he added, “Of course, you would need to leave this small coastal fishing village and move to Mexico City where you would run your growing enterprise.”

The Mexican fisherman asked, “But señor, how long will this all take?”

To which the American replied, “15-20 years.”

“But what then?” asked the Mexican.

The American laughed and said, “That’s the best part. When the time is right you would announce an IPO and sell your company stock to the public and become very rich. You could make millions.”

“Millions, señor? Then what?”

To which the investment banker replied, “Then you would retire. You could move to a small coastal fishing village where you would sleep late, fish a little, play with your kids, take siesta with your wife, stroll to the village in the evenings where you could sip wine and play your guitar with your amigos.”

It’s commonly known that other cultures treat money differently than Americans do. Other countries offer different levels of salary, encourage different levels of education, have different costs of living, offer different types of vacation time or healthcare, and have a different definition of what constitutes a “quality of life.” I won’t bother going into the specifics here, but I do encourage some education and zooming out: this will allow you to be able to analyze your own values around money more, as you compare your own values against those of others.

So, yes Sara, we learned all this shit about money. What’s there to do?

I’ll say unlearn it. It’s a journey I’ve been on for years and I’m still walking.

It was actually shocking to me when I was at one point dating a person whose mother had us over for dinner and after the meal whipped out a rib roast, saying, “I saw this at the store for you and got it! I thought you’d like it.” I actually took my partner aside and said, whispering urgently, “Why did your mom get that for you? Do we have to pay her for it?” They looked at me like I was a maniac and said, “Uhh, because she… loves me?” I was just beginning to get it.

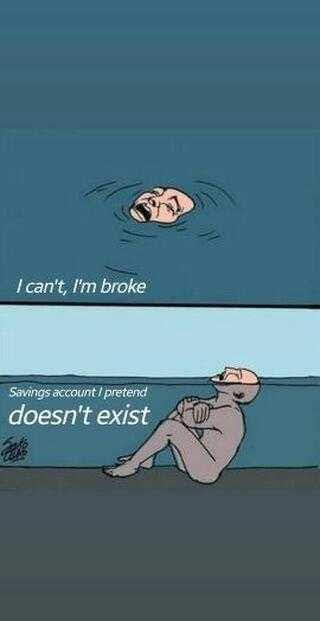

I’ve mentioned before I learned a strong script of arguing over the bill, which is related to my, kindly put, money issues. I have had to unlearn this, as well as unlearning that if you get an extra slice of cheese on your burger, it’s still not the end of the world if we split the bill down the middle. My exposure therapy comes in the form of existing in the world and trying not to focus on the bill, and trying not to argue about money, or focus on “who owes me.” It’s such a first world problem, but my homework has been to spend a little money here and there, rather than to eat a whole tomato like an apple because it’s the only food I have at the moment and I don’t want to spend money on a sandwich (this definitely happened, and people definitely judged me, correctly so, for it). I have briefed friends on my money issues and they hold me accountable and make me exit the house and get something more than water.

I was recently in Brazil — I love travelling and asking folks in other places about their values around money (if only to make my own seem all the more insignificant and less ever-present or universal). One of the people I had the privilege of speaking to spat at America, having lived there for a time, saying, “You all are so focused on money, money, money. In America, everything is money.” It sounded like a curse word. And it made me feel affirmed in my desire for something different. Less stressful. Something else is out there. A different way of being.

The more I learn about money, the more I discuss it, the more I lift the proverbial veil off of it, the less power it holds over me. I have spent countless hours fretting about money, crying about it, dreading spending it; I’ve argued over it, disputed it; it has driven a wedge in occasions that should have been fun, altered my relationships, overshadowed things I would have preferred to have been enjoying. Money isn’t the culprit as much as my attitudes toward money are. I advocate education around money, but not in the “let’s become financially literate and save every penny” kind of way — rather, zooming out and understanding money’s place in your life, and reorganizing that place to be secondary to, well, the REST of your very whole life.

I encourage you to engage in your own self-reflection and re-education around money. Zoom out and see how it goes. Ask, is this mine, or was this given to me?

3 Replies to “Let’s Talk About Money”

Comments are closed.