Millennials, we’re no longer the scornfully-looked-down-upon young generation of teens and such; we’re well seasoned — from mid-twenties to early forties at this point. We’re still struggling, but some of us are getting to a point in our lives and careers where we’re sittin’ on a lil sumthin’ sumthin’ or we’re finally in a place where a little abundance or excess is present.

Maybe not, maybe more, but my intended audience for this piece is a person who’s earning some money or accruing some savings or buying some stuff and find that they feel — guilty?! “That’s not right,” you think, and reflect back on all the fantasies about lottery winnings, all the One day I’ll… sorts of dreams you allowed yourself. Now, being closer to that than ever, and it feels kinda… not good? But this is supposed to feel good! What gives?!

Well, as I discussed in a piece long ago about money scripts, many of us were given a culturally constructed script about how we should deal with money — how we should feel about it, how we discuss (or avoid!) it in conversation, how we should spend it or save it, how to be “wise” with it, and its various correlations with success, self-worth, and power. All this mixes up into a pretty murky money soup of beliefs, values, feelings, and prescriptions in our heads. And this is true for all folks, and folks of all cultures.

Something I’m noticing in particular in millennials — and this is absolutely anecdotal, mind you — is a strong feeling of guilt around money. Let me break down some ideas about why I think this could be.

The Money Skinny

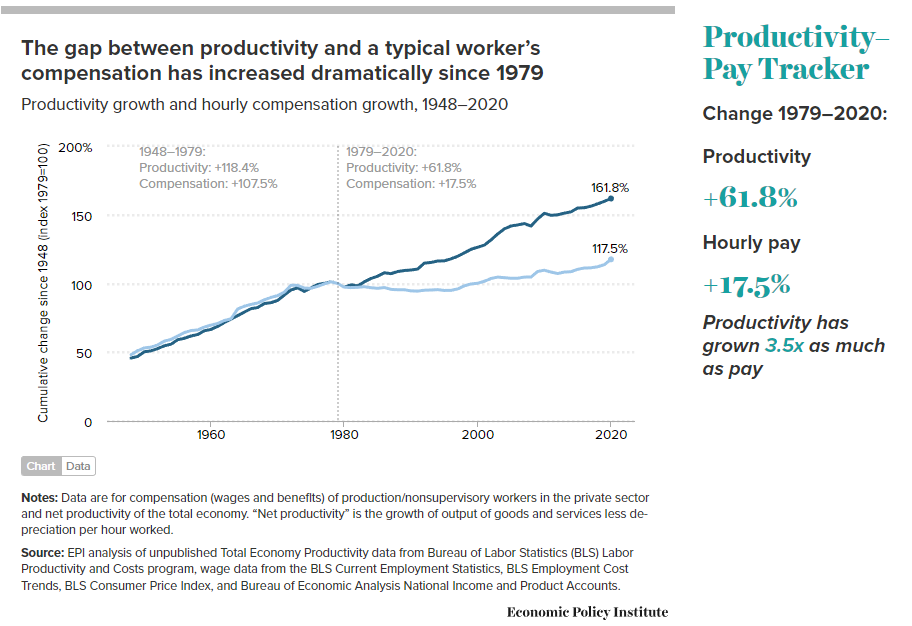

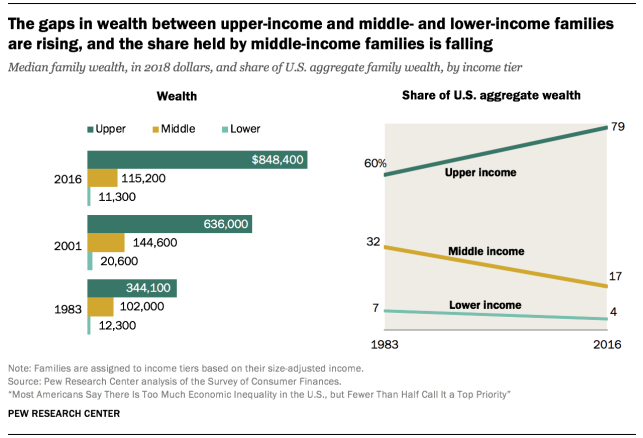

First off, let’s get a broad landscape of where we are as a society with regard to money. Presently, a huge amount wealth disparity exists in the United States — and our generation is talking about it — and without moderation, a large portion of this discussion ends up focusing on middle class people and folks in the poverty class fighting each other, pointing the finger, and playing the blame game, of course. And that makes sense, given human psychology — we are led to believe that it’s better to at least have someone else beneath us to blame. The upper class, the ones with the power and the influence to make real, lasting change, as well as the ones who can buy politicians’ opinions and hot media spots, manipulate the message to retain power, and that message trickles down that problems are our own individual faults, or the faults of those who have it harder than us, or have less privilege. It’s better for those with power to cultivate in-group fighting among the lower ranks lest the lens of critique rest on them. So it’s meritocracy all over again, the belief that hard work will lead to desirable outcomes, the dream that America was built atop, only it feels harder to achieve than ever, given the rising rates of income inequality and stagnant wages. The flip side of this is, If I’m doing bad, it must be my own fault or because I’m not working hard enough. The result? Guilt.

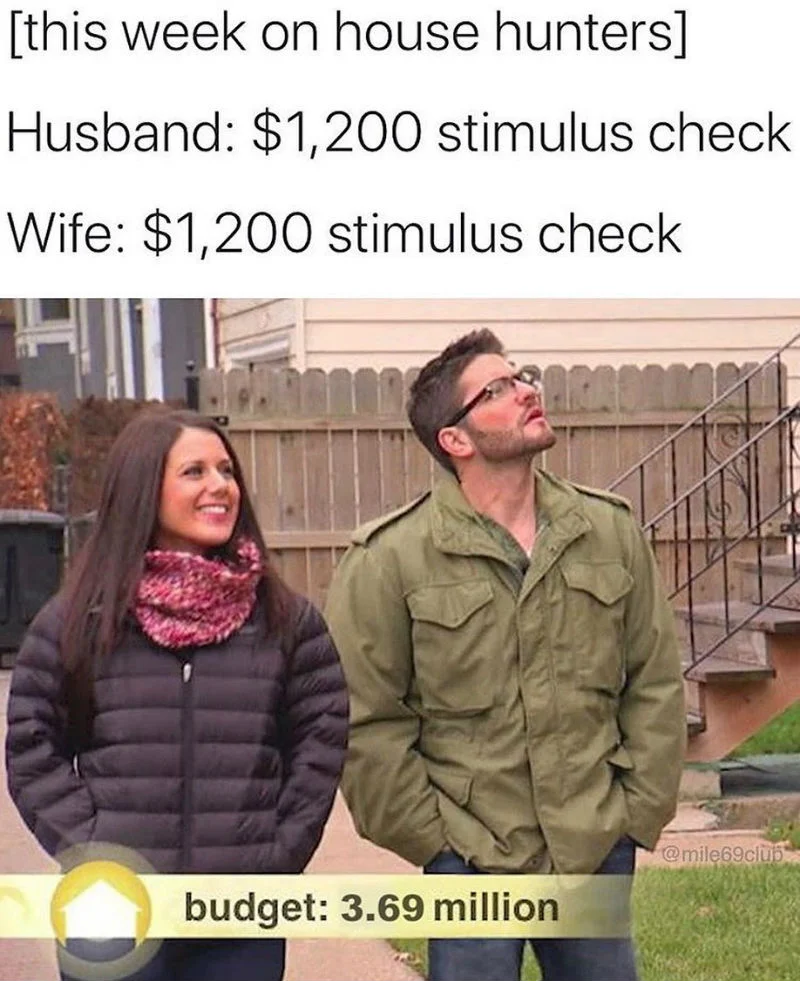

I remember growing up watching MTV and they had a show called MTV Cribs where they showed ridiculous houses that people spent huge amounts of money on. This was one of many programs where they showcased folks spending exorbitant amounts of money on stuff and it was laid out like something to aspire to — let alone that I will never have that kind of money or that kind of house.

There were a bunch of shows like this — here, on HGTV, whatever. A person who is a basket weaver having a 3 million dollar budget for the home, that’s the joke. Folks in my generation grew up with the starry-eyed wonder of lustfully looking at the mega-millions yachts and mansions of the ultra-rich, dreaming that they could one day attain something similar. People wanted to watch some show about the Kardashians, or see a person win the lottery, or have a wild spending spree. And we were told that we could have wealth and a life of comfort too, if we attended school and worked very, very hard and got good grades and a degree and all that stuff. And for those folks who were privileged to have those opportunities, myself included, it moderately panned out. But not like what we were led to believe growing up in a culture of folks absolutely fellating and licking the boots of the ultra-rich.

The culture around how we view the ultra-rich has changed since then. Sure, there were always folks crowing “Eat the rich,” but that belief seems to have become more mainstream now as the narrative continues to shift. Why is this?

Maybe it’s because US Billionaires became 62% richer during the pandemic. Maybe it’s because the top 1% have 15 times the wealth of the bottom 50% combined. I can keep going, but it’s a bit of a mess out here, and we’re exposed to this constantly. And that’s all well and good, because it is helpful that this is transparent, but it also is incredibly depressing to a person busting their ass, barely making rent (which is rising at a very high rate vs. wages), and trying to “hustle” just to get by. The dreams we were led to believe were possible became a far cry. And living is expensive.

So, we have good reason to feel a bit of a strain here in the US. I can talk endlessly about this, but I’ll cut it here because that’s more to expand on for another piece. For now, the takeaway is: it’s a stressful time to exist as a person with financial responsibilities over here, and folks aren’t provided with enough adequate tools or chances for financial success. I was taught lessons about finances and success that I feel no longer apply to the present economic landscape.

What else did we learn about money? What other financial scripts were given to us? Let’s think.

Money Scripts

I was taught not to feel bad about the things I do have because there are people starving in other countries. This is fair, and the United States is the richest country in the world. I acknowledge that I have a lot of privilege inherent in having been born and raised here, and in continuing to reside here. There are certainly many opportunities for success, wellness, and wealth building that are not present in other geographic areas. That said, the messaging of “others have it worse,” while absolutely true, is one that places guilt on the person hearing it, as though they are not allowed to find their situation hard, or that they find it hard because they are ungrateful or of bad character. This sort of messaging promoting comparison is another reason why young people may find that they feel guilty when working to examine their relationship with money.

There’s a trend in millennial culture about “the grind,” and that it’s beneficial to have a variety of streams of income. This is embodied in “”side hustle” culture, where folks aim to have another job in addition to a full-time gig. This sounds good — who wouldn’t want to diversify streams of income?

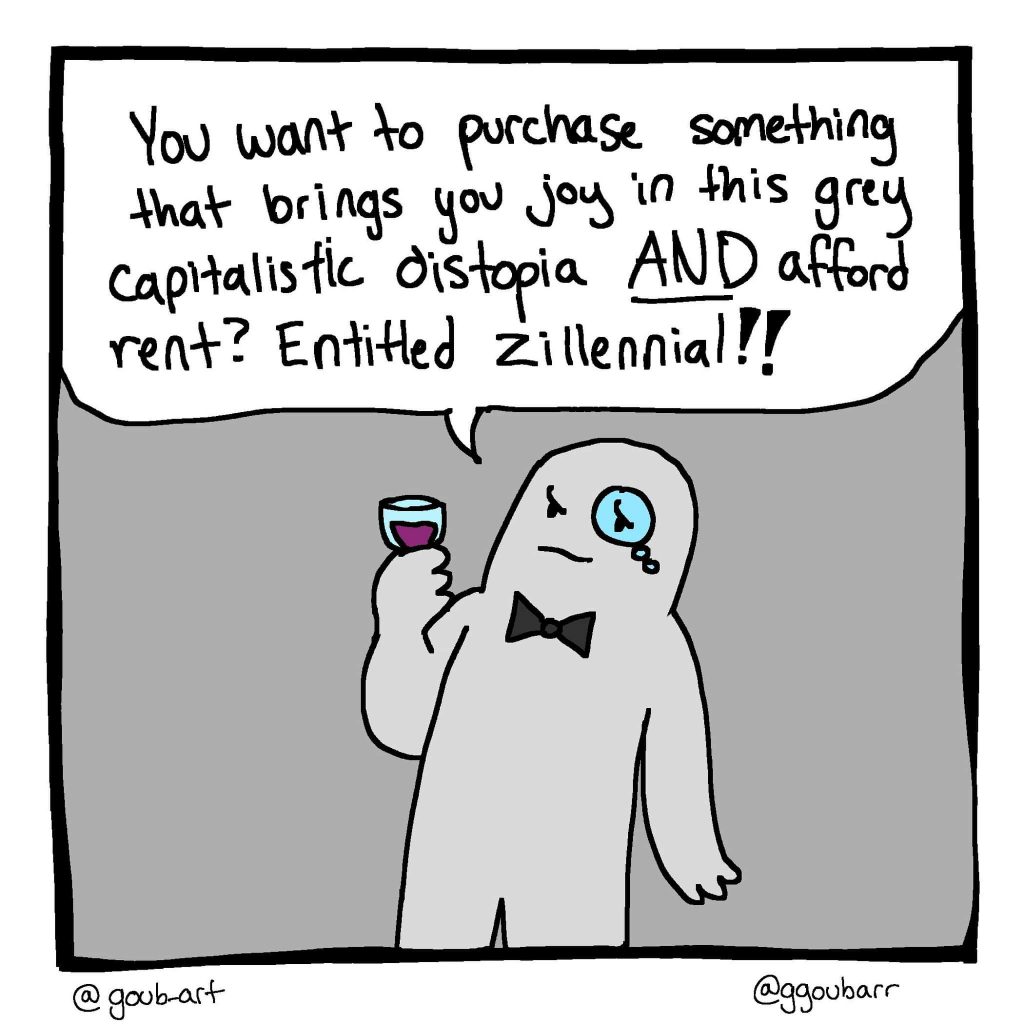

The downside is 1. We exist in a culture where having one job is no longer “enough” to get by (Per person, even!! The 40hr work week was made for one person to sustain a whole ass family), and 2. Folks feel pressure to work at the expense of other endeavors such as hobbies, relaxation, and wellness.

“But monetize the hobbies!” The capitalist grind tells us to consistently be thinking about making and maximizing financial gain. But at what cost? People can inevitably end up feeling like free time is “wasted” if they are not using it to earn money, leading to burnout, stress, and guilt. Not a great recipe for wellness.

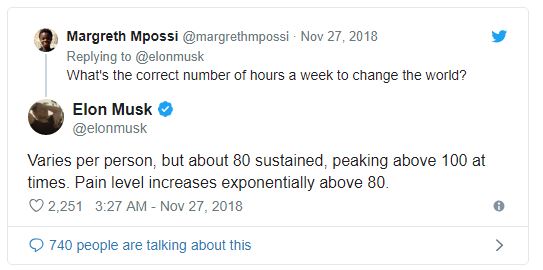

Have you ever been in a space where people were bragging about how little sleep they got the night before? There’s a cultural script that exists wherein folks promote suffering as a way of being, and use it as a measuring stick for hard work and success. This is especially prevalent in certain industries, including startups and trades. Many promote the idea that working ridiculous hours is “the norm,” or something one should aspire to. Or, if folks were to value a work/life balance, or have interests outside of the ever-consuming need to work, this could be a bad thing worthy of guilt, indicating laziness, selfishness, or some other negative trait one might do well to feel guilty about or change.

Here’s some tweets from one of the richest men in the world promoting this idea —

The unfortunate thing about such ideals being promoted is that although management would of course prefer we work this much (particularly if we are salary!), it also gets passed down and repeated by our peers. This kind of behavior is like crabs in a bucket — although our peers likely mean well by also subscribing to and repeating these ideas, it can lead to pressure to work so much that it leads to burnout, coming from messengers we would like to believe are more reliable as there is no inherent power structure to prescribe it. But alas, this programming goes deep.

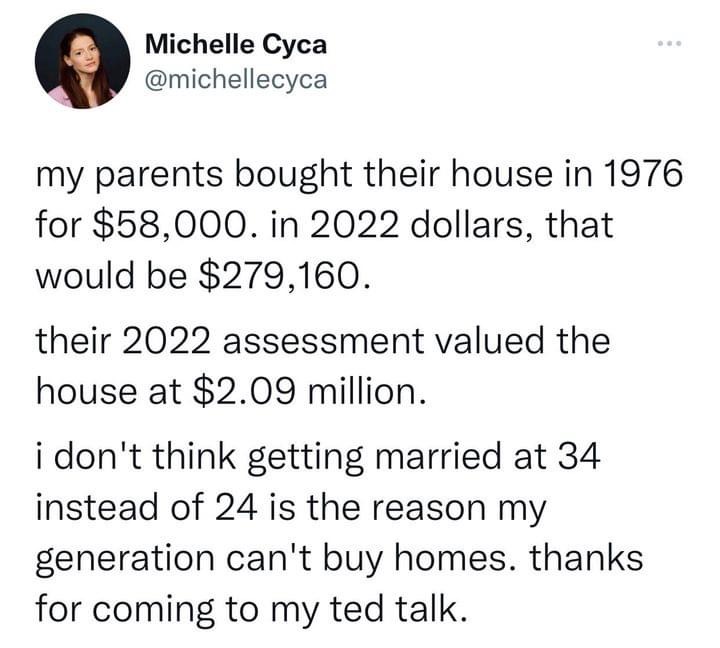

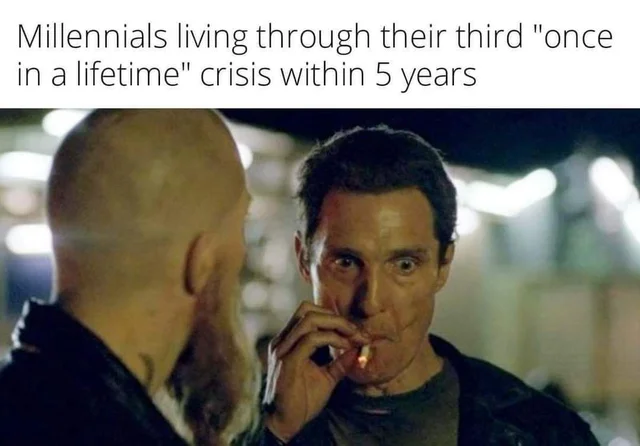

In millennial culture, as aforementioned, folks are talking about this stuff more than ever, and it spreads like wildfire through social media posts and memes. The discourse is important, consciousness-raising and rife with activism, and it’s also humorous, sardonic, collapsey, stressful and morose. There’s jokes about not buying a home, killing industries, spending too much money on avocados, and the like. And these messages can cause stress and guilt in millennials, who are just trying to live a life over here. A few of these headlines —

“Millionaire tells millennials: if you want a house, stop buying avocado toast” — yes, millennials, it’s your fault that you can’t afford a home, because you spend on frivolous things like avocados, which has of course led to you not having $60,000 for a downpayment. There’s well-meaning financial “advice” all over the place, from randos to billionaires to talking heads whose jobs are to talk money. And the advice of “stop buying lattes and then you’ll stop being poor” is kind of a hard circle to square; while it is important to have a budget and to be “smart” with one’s money, the kind of blame and guilt messages on folks for their own failings in the wake of financial and political crisis after crisis is quite difficult for millennials to bear, I’ve found. Self-sufficiency and planning is important, no doubt. But to say it is the only variable responsible for one’s success in the financial world is unfair, unrealistic, and misleading.

Many scripts exist to paint the message, “Spending money bad.” As though folks should scrimp and save, and have their main goal to be to accrue as much capital as possible, like an old-timey dragon just sitting on and admiring his treasure hoard till kingdom come. This kind of messaging gets passed down, and may lead folks to feel guilty when they spend money, whether on personal items, interests, even on necessities.

I received a lot of this messaging growing up. I remember getting my first job as soon as I legally was of age to, and saved up all that minimum wage grocery store money that I could. When I reached my goal, which was to buy a Zune (showing some age here), I received criticism on my frivolous purchase. I was young! Therefore I should save for the future, which was uncertain. Why wasn’t I thinking of my future college expenses at 16? I was trying to survive being a teen, and music felt important to my survival at this time. It’s hard for me to recount this memory because I have more forgiveness for that young person I was, now. However what this experience imparted in me was a self-monitoring about my money, and a large guilt at the prospect of spending money on myself, on frivolous goods, basically on anything but necessities. The reality is, which I now know, is that one will spend money on a good balance of things — necessities, living expenses, health and wellness, and diversion and entertainment. A full life consists of many aspects.

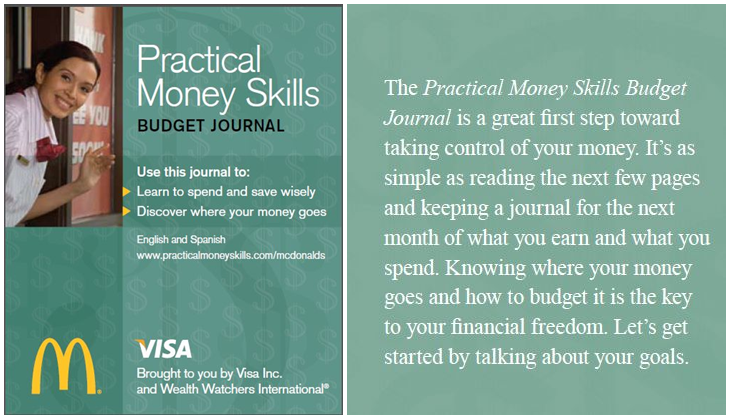

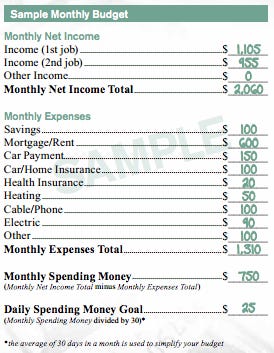

The budget released by McDonald’s — along this vein, a sample budget was released by major corporation McDonald’s to millennials under the guise of teaching them better how to succeed by budgeting one’s money. The problems with this model become readily apparent with some scrutiny, however; it presumes that one must work two jobs to succeed (here defined by barely scraping by and living to work), and the expense predictions are absolutely unrealistic, particularly now. Folks who simplify the problem into a cookie cutter budget, again, are missing a large part of “the problem.” This sort of hand waving does little to solve the problem, and much to contribute to negative feelings about money in its recipients.

How about how millennials are killing industries? I’ve heard of millennials killing diamonds, Applebees and other chain restaurants, napkins, and a myriad of other things throughout the years. And although folks might acknowledge that this is just a free market at work (supply and demand, anyone?) an underlying message that often goes unspoken is the tendency of such ways of framing the economics of millennials to impart blame, shame, and guilt.

A lot of people are telling folks how they should work, spend, think, and feel about their money. A group for whom this is particularly present are first-gen folks; those whose parents newly came to this country to carve out a better life for them. There’s a lot of pressure in this situation that can be passed down, from parents who may say “I came to make a better life for you!” which is a true and poignant situation. However this feeling can be hard to bear for some folks who find they have large shoes to fill. This same sort of feeling can also be felt to a similar extent from folks who grew up poor, or watched parents struggle in tough work and financial situations, and are encouraged to ascend that situation. Children in such instances may feel guilty, worried, or feel that they are not enough. Folks may find that they feel guilty for feeling like it is hard to succeed, or that their successes might come too easily compared against the model of their parents.

There are also a lot of stressful, once-in-a-lifetime social and political events happening presently. Environmental and climate concerns, increasing exposure to violence, political and cultural division, financial crises, rollbacks on civil and consumer protections and rights, all lead folks to feel quite negative. It’s hard to be quite positive about the future and money in the wake of all this messaging.

Likewise, alongside all of this messaging comes messages of guilt. When talking about environmental conservation, for example, many companies promote ideals of individual responsibility, asking consumers to lessen water usage, or plastic usage, or use services like climate control less. While personal responsibility is very important to addressing concerns of climate change, for example, it misses a large aspect of the point, which is that major companies are by and large responsible for the majority of pollution affecting the world today; just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of emissions since 1988. While it is important for consumers to do what they can in instances like this, whether it’s to drive less, or produce less waste, or recycle or whatever, the “Do better” messaging when it relates to the environment largely misses the point. It seems to follow along current culture messaging which is to create guilt and responsibility in folks while concurrently missing the larger point, which are the other contributors to the problem at hand (whether income inequality, or corporate pollution, or what have you). Again, this sort of messaging that younger generations have consistently received is likely a large contributor to guilt that folks feel in response to these topics, whether financial, environmental, political, or otherwise. It seems silly to stress about one’s extra minute in a hot shower when companies are constantly spilling millions of gallons of oil in the ocean.

These sorts of cultural messages lead to folks performing actions like virtue signaling and gatekeeping. Virtue signaling here means demonstrating opinions or actions with the purpose of displaying one’s good character or traits, like when a person videos themselves donating to a housing insecure person and then posts it online for their peers to view. And gatekeeping here refers to controlling and limiting access to something. What these terms mean in this context of financials, culture, and guilt, is that it is presently in vogue to display one’s opinions and actions in full view of others, and in doing so a person may build a reputation, whether publicly or by forming and adapting one’s own internal opinion of oneself. If a person finds they do not meet the model they feel they “should” be measuring up to, for example such as by being able to donate to a charity in a certain amount they’ve seen others do, or having time to devote to causes and interests, they may feel great stress, guilt, and judgements of themselves, and fear of judgements from others.

This is compounded by cancel culture, wherein a person may face ostracization for doing something that may be deemed to be unsavory or in poor taste. Folks fear negative reactions from others, and negative representations of their own character, that’s reasonable. It seems to me that the “Keeping up with the Joneses” script from before (needing to keep up with financial purchases, spending, and items that others might have in order to perform, keep up appearances, or feel one is “doing well”) has been adapted with an additional layer of fear around one’s character, goodness, or potential social reactions including ostracization. This here meaning, folks may find it harder to succeed than ever before due to environmental and market concerns, feel worse about it because of social and cultural scripts, and fear backlash, judgment, and ostracization from others because of current cultural scripts and social media.

So what do we do with this?

The reality is, some of us will have more, and some of us will have less. Some will be able to change their situation, and some will not. Some folks will improve on their financial situations, and some will face consistent hardship, despite hard work to the contrary.

It’s important to recognize the cultural and social contributors to our own internal feelings and reactions. I understand that our feelings happen inside, so it’s quite hard to pinpoint them to external sources, but it important to be aware of the tendency we have as social beings to absorb and implement scripts into our daily lives. Perhaps we have reason to feel guilty about financials, and some of this is innate. But it is also my firm conviction that much of our feelings of guilt around money are also a result of learning we have done. It’s ok. We are smart, that’s why we learned these deep lessons in the first place. Having more compassion for ourselves and our peers in the wake of tough cultural scripts is important to our continued growth and wellness.

It is important to understand money. It’s a constant in our life, and barring large societal collapse, it will continue to be. It is important to confront our discomfort about money, and learn to have a relationship with money that is not avoidant, confrontational, fearful, or guilt-ridden. This seems like a tall order, and that’s reasonable. That being said, it’s important and helpful to continue to face “money stuff” head on, and learn about money, try out budget stuff, look at that bank account, and have brave conversations about money and its role in one’s life. It’s helpful to understand one’s goals and keep them in mind when considering planning one’s finances, whether short-term or long-term.

Giving back is great. If a person is in a place of abundance, sharing that abundance is beneficial. Understanding one’s own boundaries and feelings around, and needs for money, can help a person to understand their capacity to give, whether that’s financial, temporal, emotional, labor-based, or otherwise. Understand better your need or desire to give, and look at it in context. Sit with and understand a desire to post or share about one’s money or giving.

As an individual works on understanding their relationship with and feelings around finances better, this can extend beyond them personally. Folks may discuss this with others in their circles. Having conversations about money is OK. More than that, it is necessary. Folks talk about money with friends, loved ones, colleagues at work, etc. I talk about money quite a bit as it is a necessity in a therapy relationship. Therapy is a weird relationship where there’s genuine care, compassion, concern, and empathy, and money is also involved. But is it that weird? Couples discuss money, friends split the bill, contracts are negotiated with employers. Money is an important and unavoidable part of life. Modeling healthy conversations about it is important, and is also important in dispelling guilt around money’s concealment. Understanding, acknowledging, and following boundaries around money, and welcoming conversations around money can be a sign of great respect and growth around folks.

Setting boundaries around money is OK. It is necessary. Whether this is in the context of a business agreement, a work contract, or in a relationship, giving voice to one’s ideas and needs around money is helpful, important, and necessary. The more familiar one is with their values and beliefs around money, their needs of money, and their related feelings, worries, and blind spots, the better they can advocate for themselves around this ever-present reality of existing as human.

Guilt around money sucks. There’s a lot of reasons that it’s there, for many people. Thankfully there’s quite a bit that can be done to welcome in a better personal relationship with money.