Hey — here today with a quick tidbit.

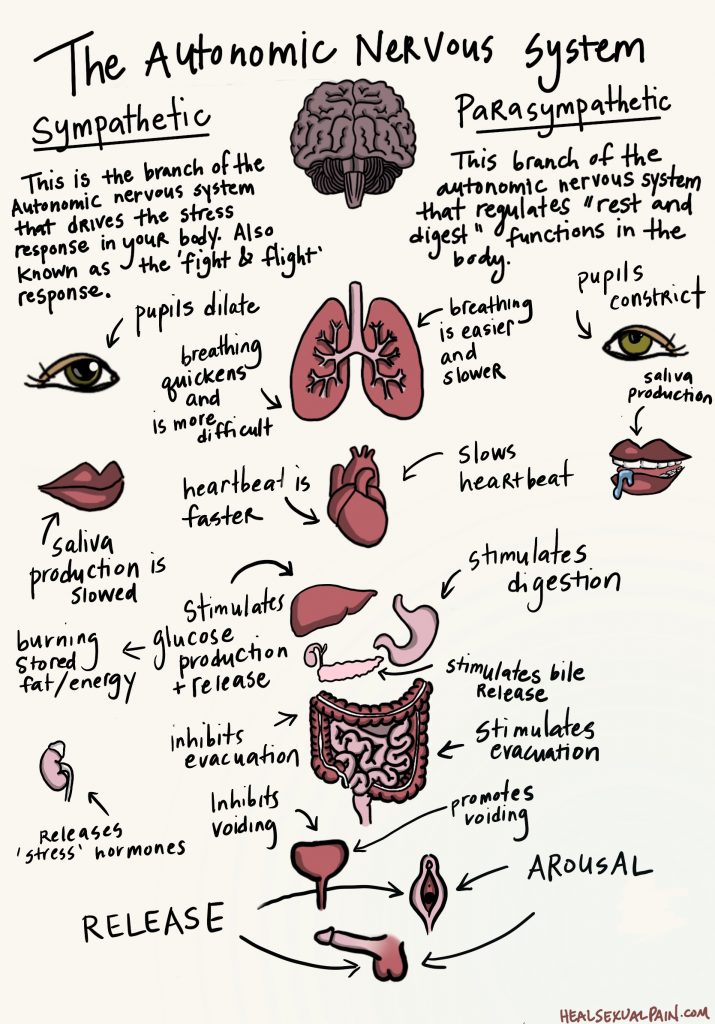

We’ve heard of the fight or flight response. It’s when your brain senses danger, and kicks into what we nerds call a sympathetic nervous system response: a cascading series of events that happens to allow us to fight, or flee, thereby prolonging our longevity, and therefore the species. It’s an evolutionary mechanism that’s hardwired into the brain.

Now, as you’ve heard of the fight or flight response, it would then make sense when presented with a stressor, that one might react by either fighting or fleeing. School stresses me out: I can do the schoolwork and take it on to get’er done, or I can cocoon at home and not go in. My relationship endures a snag: I might yell at my partner and release the tension or I can go into my room and brood. A spider presents itself in my house: I might try to smash it or scream and leave the area, enlisting help.

Now, of course these aren’t the only options; but the ones I’ve presented also make sense given the way the human body and nervous system reacts to stress. I think this series of events happening to the body and the resulting reactions was named as such when looking at reaction mechanisms of more primitive organisms or situations; fight or flight are pretty much the only options when presented with a saber tooth tiger, or when you’re a mouse who just ran into a cat.

I want to expand on this too, though, fight or flee are not the only options. As I’d mentioned before, “freeze” is also a valid option too, when flooding happens to the nervous system, sometimes the only thing left to do is freeze and shut down. This is a reasonable reaction to substantial stress: sometimes the best option is to play possum and, just, “leave” the situation behind and hope it might resolve.

This could look like dissociation, or a panic reaction, or shutting down when presented with a substantial stressor. The body shuts off power and runs accessory lighting for a while, so to speak.

Now, there’s another reaction in there, and it’s also reasonable, like the rest — we call it fawn. The fawn reaction is when a person presented with a stressor instead of freezing or choosing to react in a combative or fleeing way, tries to “play nice” and placate a source of stress. If you’ve ever seen a dog meet another dog and then act in a very meek way to gain the trust and confidence of the other dog, you’ve seen it — tail lowered, head down, dog making itself look small and not dangerous, putting on its best behavior to be nice so as to not be attacked.

The fawn reaction in people can look like:

- “My partner has a tumultuous and traumatic relationship history with their parents. When around them, they become very meek and placating, trying their hardest to accommodate their needs and wants, almost waiting on them hand and foot. I find it odd because they don’t really like their parents, but they’re scared of a blowup.”

- “My boss is such a jerk. He gives everyone horrible feedback and makes rude remarks all the time. I take great pleasure in complaining to my coworkers about him. I hate him. But when he called me into his office last Thursday, I fell in line, with all the ‘Yes sirs’ and other shit.”

- “I had a troublesome relationship with a past partner who was abusive. I never want to see him again. But when I was at the bar over the weekend, he approached me. I was nice to him and asked how he’s been doing and we had a conversation. I don’t know why I did that.”

Now, this reaction can elicit a bunch of reactions in the person having it, much like one judging oneself and feeling some type of way about it. And again, this is a normal human experience. The above folks might have these experiences following such events:

- “We talked after his parents left from that long weekend here. He was telling me he felt exhausted from seeing them and being on his best behavior, but he also told me he feels ashamed of being so nice to his parents. He said it makes him feel like less of a man or not really an adult. I guess he wishes he could stand up to them but feels so afraid in the moment.”

- “I feel like a total loser for having to kiss my boss’s ass. It makes me feel so stupid that in the moment I can’t stand up for myself. Am I a weakling?”

- “I feel totally betrayed by my reaction; I promised myself I’d never talk to him again. He was so terrible to me when we were together! He is disgusting! I feel horrible. I feel like I’m just welcoming him back into my life, like I’m powerless. I give him the impression everything’s ok! I must really just want to be treated like that.”

Having a fawn reaction is a natural and normal response to stress, and often relational stress, because placating and playing nice is a very viable option when dealing with tough or abusive folks who we can’t just necessarily ghost or whatever.

But it becomes troublesome when folks reflect on their actions with self-judgment and blame. And I get it, it’s understandable that one might look at an interaction like the above at surface value and see it as though they “welcomed” it, I guess. People generally want to make sense of their actions and situations, particularly stressful ones, so they can react better in the future and not endure such stresses or feelings of unsafety again.

Understanding what the fawn reaction is is an important step in self-compassion and dropping unhelpful aspects of self-judgment. “Fawn” is an instinct, for us just like it is for a good dog at the dog park. It’s a reaction that we don’t always have conscious control over, as more primitive brain and bodily stress responses take over and direct some actions for us in order to ensure our best shot at safety and survival. The fawn reaction tries to protect us by appeasing a dangerous presence, thereby de-escalating tense situations.

You’ve seen the script before: a woman is sitting at the bar and a man approaches her. He’s throwing off red flags: he’s intoxicated, he is pushy and too touchy-feely, he’s loud and obnoxious to another man at the bar. Alarm bells go off in her mind, and her stomach tightens. She clutches her purse tightly as he tries to talk to her. Rather than confront him with a brash tone, or ignore him entirely, both which might lead to a loud and scary confrontation or escalation of worrisome behavior, she instead smiles, plays “nice,” engages with his company but keeps it short in the hopes that he will move on. This is a reasonable fawn reaction. And certainly not a defense he could or should levy should something happen: “But she smiled at me so obviously she was asking for it!”

Look, I know we live in a society that is often unfair and unjust, and others might use a fawn reaction against a person. And that’s majorly fucked up, and gives the impression that trying to play nice while terrified out of our gourds is permission for whatever to happen to us. But that is not the case. Power imbalances, fear, lack of safety all play into situations and are not cause for presumed consent.

That said, the trouble is the reactions we then levy on ourselves as the result of these social scripts. We might internalize the message of, “Well obviously I welcomed it because I didn’t tell him to fuck off, or leave when I knew it was going to go poorly (read: fight and flight, respectively).” BUT, sometimes a freeze or fawn reaction comes up: we shut down in fear and remain frozen to our barstool. Or, we play nice, fearing an escalation if we don’t follow the script. It’s why saying “I have a partner” feels less terrifying or more appropriate than a more true, “No, I don’t want to go out with you,” as the latter is scripted to cause more offense, yielding a potentially more dangerous interaction. And so many people find themselves in these situations every day, where “playing nice” is their best bet at escaping a situation safely.

It breaks my heart when folks judge themselves negatively for having a necessary fawn reaction to a situation. Often folks are doing what they need to in order to live another day. It’s unfortunate that sometimes there’s a shame response to that, and that feels societally baked-in with a lot of the victim blaming we’ve been exposed to. I feel it.

And in a way, I get it: the self-blame is a false measure of safety; one saying, “Well, if you do something differently next time, you won’t be hurt again! We have power and control over our actions and therefore the situation.” Whereas often in reality, unfortunately, we don’t have control over the actions of others who choose to disregard our wishes, our safety, our wellbeing, or our consent. Sometimes, having that feeling of safety or self-control is more important in the moment than anything else, so blaming ourselves feels prescient. I hold space for that.

Oftentimes, a fawn response is learned and reinforced in earlier life situations, if folks endure difficult or abusive familial, relationship, or living situations. That’s not to say it comes from that, as I’ve established it is instinctual. But, sometimes when we practice a method to survive, it might become the norm more as time goes on. Folks with a substantial fawn response might find themselves emulating people-pleasing behaviors in other aspects of life, even if not exposed to chronic or acutely stressful situations. They might engage in altruistic behaviors, disregarding the self, or focus or fixate on self-blame, doubting themselves and their actions or intentions, impacting their self-esteem or self worth. Folks might feel afraid of conflict, and might try to avoid it as much as possible, sacrificing themselves in the moment. Again, fawning is not a bad thing, but it is important for one to develop insight into one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions, if stuff is happening in their lives that doesn’t quite feel right or good to them.

It’s helpful to continue to develop one’s emotional intelligence, and strengthen our metacognitions to better understand ourselves, our biology, and the fabric of the way we think and feel. Sometimes discussions about this with a trusted friend or loved one or therapist can be helpful in continuing to build these reserves of strength and self-knowledge up. Learning about and practicing setting boundaries is an important step in moving forward from people-pleasing habits. Of course, in order to do so, acknowledging, taking care of, and building our internal sense of safety is also important in combating fawn reactions that previously felt necessary for survival. Extending trust in others, and practicing confiding in, and delegating to others is invaluable self-work. Catching oneself in patterns of fawn behaviors can be helpful for understanding one’s reactions and motivations, and comforting and caring for oneself in the future — these can look like defending oneself, overly apologizing, taking on a small or meek stature or voice, and overextending oneself emotionally or physically, among others.

We are not villains for having biology that influences the way we care for ourselves and keep ourselves safe. A fawn reaction is a reasonable reaction to present stressors or dangers in our lives. Sometimes it comes about because it felt necessary, and sometimes it can be untrained and moved forward from, much like a vestigial organ that is no longer necessary for our current living situations.

2 Replies to “Fawn”

Comments are closed.