Hey there. Happy Pride month!

As a preface to this piece, I would like to acknowledge that I am a queer, white cisgender woman, and a strong ally to the trans community. I was raised by straight parents in a middle-class, vaguely Christian faith upbringing that now no longer means much to me. I grew up in the 90s when people didn’t know what the fuck was going on with sexuality let alone gender, and folks regularly used “That’s so gay” to talk down on something without questioning the pain such remarks caused. I am straight-passing at times and femme-presenting. These experiences and identities among others affect my interaction with this piece. I recognize I benefit from various layers of privilege that color my writing and interaction not only with scholarly topics and research but also in understanding personal accounts of others, whose various intersections of communities and identity differ from mine. Although I do my best, I sometimes get it wrong. I welcome interaction on my writing, suggestions on how to do better and be better, and feedback which I can incorporate into my work on this matter. In this piece, I am going to cover a broad overview about gender and sexuality, and although I do understand what it is to be a member of the Queer community in some regards, my understanding is also shaped by my personal and professional experiences and at times might be perceived as quite myopic in scope or not quite “covering” it. My intention in doing so is to offer my support to the LGBT community, and provide an accessible resource to persons I see to discuss gender and sexuality, particularly parents of LGBT folks, who would majorly benefit from a straight-talk, affirming, accessible 101-level overview of such topics. I’ll also try and include an overview of some often-used terms to this end, but again I don’t presume to be an expert, or to even cover all necessary information in this piece. My first and foremost suggestion in continuing your scholarship and understanding on these matters would be to seek out diverse materials and accounts from folks elsewhere in the Queer community, who come from different traditions of faith, culture, socioeconomic background, race and ethnicity from my own as well. I will make recommendations later in this piece on some suggested materials, organizations, and resources that will be beneficial in expanding your views on sexuality, gender, and its intersections with other important aspects of identity, culture, and life.

I’ll also start this off by emphasizing, I fully support trans rights and queer folks, and all who fall under the LGBT umbrella. Love is love. Trans rights are human rights.

Let’s look at some terms I will use here.

Terminology

LGBT is a term I will use as an umbrella interchangeable with the queer community. There are varying levels of this acronym, some with more letters and some with less (LGBT, LGBTQ, LGBTQIA+); know I fuck with them all, and support identities of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender it represents in short form, and also support folks who are nonbinary, intersex, asexual, and all those who fall in various umbrellas under these terms and acronyms. I will do my best to represent experiences from these communities and explain a broad and brief overview of what these terms mean to readers who might not be familiar.

Queer is a word that has held many meanings over my short (ish, come on) life so far — at first it was a word that meant “odd,” or “weird,” then it was a derogatory term or slur used to punish, persecute, and other folks who weren’t perceived to be “straight enough” or “cisgender enough,” whatever that means, and now it’s being reclaimed as a term by the LGBT community, and is one I quite like. Folks might still have a knee-jerk “yuck” reaction to this word, which is understandable because it was used so foully before. Please know my use of it is affirming and I use this word to refer to myself, often, and it brings me great joy. We are allowed to feel differently. Often I use this word interchangeably in this text to refer to the LGBT community or folks within; generally, to me, it just refers to folks who are not cisgender or heterosexual, existing outside of some privileged social norm that is put upon us by society and culture.

Sexuality refers to one’s sexual preference or orientation, yes, but also is an interactive word used to describe a breadth of things, including gender and one’s relation to it, sexual behavior, sexual performance, sexual feelings both outward and inward, sexual preferences, and so on. A more precise or familiar term to be used will be sexual orientation, which is a way we describe a person’s preference for others, whether romantically, sexually, or both and generally somehow relies on the gender of both speaker and desired person (examples – gay, straight, bi, heterosexual, homosexual, etc.).

Gender, also sometimes referred to as gender identity, relates to how a person performs masculinity, femininity, both, or neither. This relates both to cultural expectations of gendered roles and performances. Gender may or may not be in line with biological sex, and is not dependent on pronouns, behavior, or appearance. Anyone, cis and trans alike, may choose to experiment with their gender presentation which may include or not include any number of things such as trying out a new name or pronouns. Any and all gender expressions and identities, be they masculine, feminine, or in the middle, are valid.

I know it potentially sounds like I’m being intentionally vague here to some, but this is not the case; there’s actually so much wiggle room in these terms that one might not have been exposed to prior.

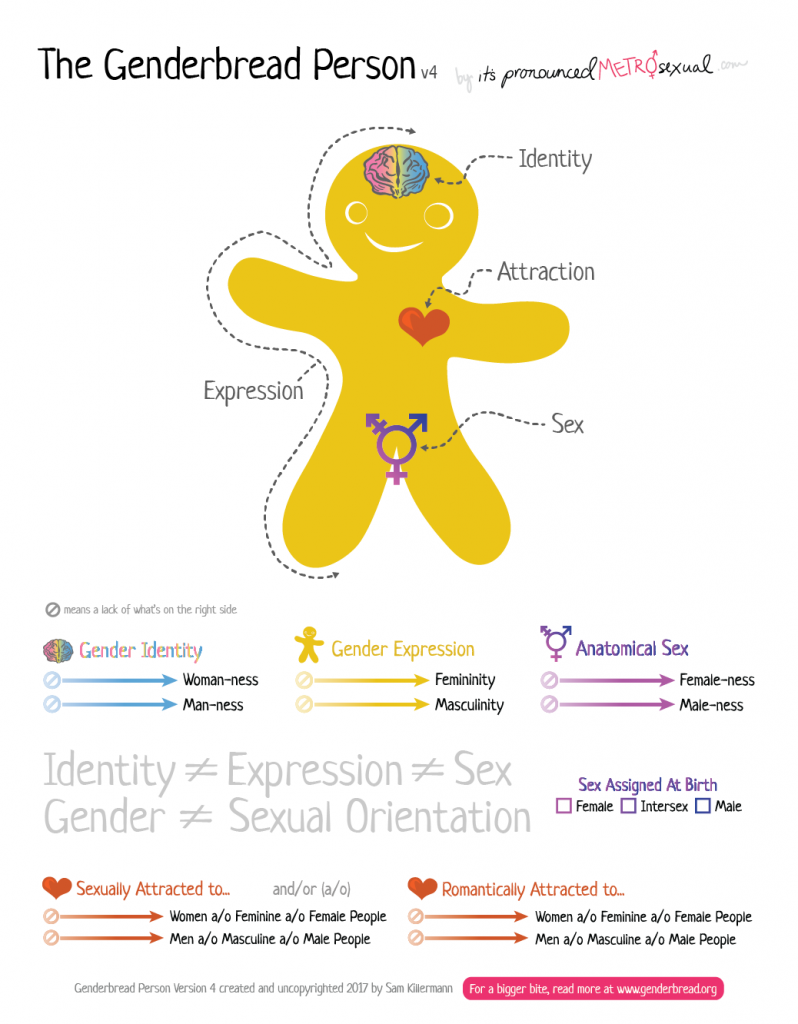

For a great overview of these topics, I highly recommend checking out the Genderbread resource, which uses great diagrams and language to make a complicated topic a bit more accessible.

Let me break it down a little more using the image above.

Gender Identity refers to a psychological sense of self, how folks identify themselves in their head and who they feel themselves to be, whether referring to a concrete identity or a place on a spectrum. People might feel more aligned with female-ness or male-ness, or neither, depending on what this means to them. This is changeable throughout one’s lifetime.

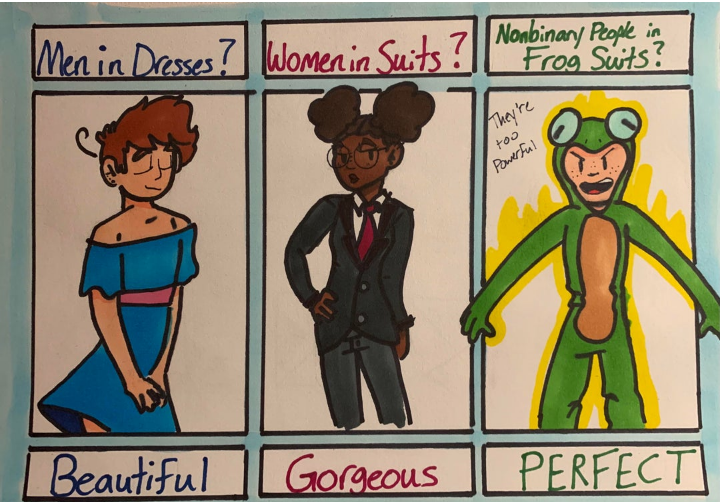

Gender Expression explains a performance of gendered identity, which people may express outwardly through actions, clothing, demeanor, posture, and more. Gender expression interacts with societal gender norms, which others use to interpret one’s performance of gender. Gender does not exist in a vacuum, and always changes based on where we are located geographically, culturally, temporally, and more. For example, wearing a kilt will firmly place one in the “Manly man” category when in Scotland, or when attending Celtic Fest here in Bethlehem. However, doing so outside of this context, or in an area where men face great repercussions from defying norms, and where kiltwear is not the norm, might be seen as a feminine gender expression. It’s all in context.

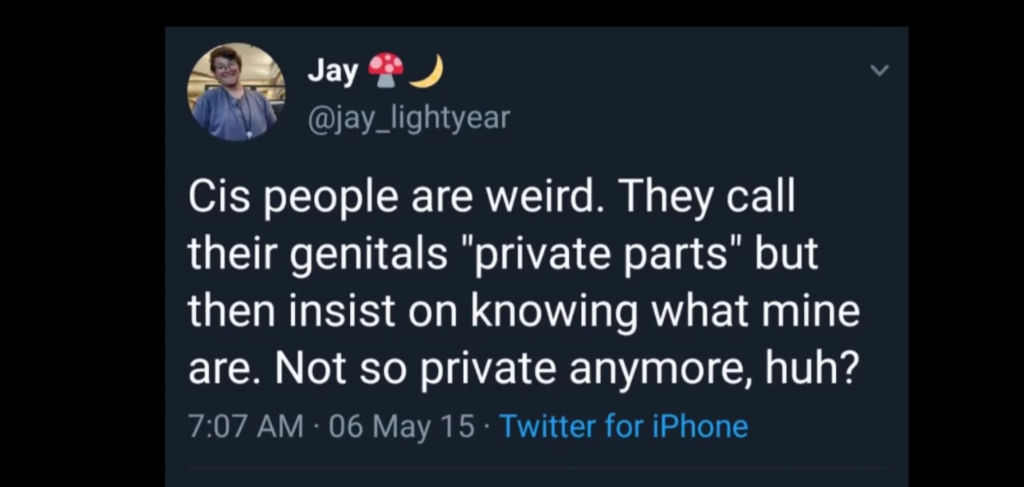

Anatomical Sex, Sex, or Sex Assigned at Birth refers to a person’s genitals, chromosomes, hormones, and secondary sex characteristics like chest, body hair, fat distribution, etc. Chromosomal sex, secondary sex characteristics, genitals, etc. don’t always line up even in the same person. A person’s body can be hormonally female, chromosomally male, and present with male genitals and female secondary sex characteristics, etc. It’s all a big jumble. All of these are just data points — the reality is that we take people at their word for how they identify or perform gender things, and leave the physiological, anatomical, hormonal, and genital wonderings and concerns in the hands of their privacy and medical team.

Attraction refers to what people like like. Attraction can be broken up into various forms, most known are Sexual Attraction (which refers to folks’ sexual preferences and interests) and Romantic Attraction (which refers to a person’s romantic proclivities or desired ways of relating).

A quick note regarding attraction — we live in a culture of compulsory sexuality. Persons are presumed to be sexual and feel sexual and romantic attraction. It’s also possible that someone might not feel these desires, or feel them on a varying spectrum, which can be troubling in a society with compulsory sexuality, leading to folks feeling othered. It’s a valid identity to be asexual or ace, in varying forms, which generally describes feeling little or no sexual or romantic attraction or desire (it’s a spectrum). Folks who feel little or no romantic feels or attractions might labels themselves as aromantic or aro. Ace folks might lead sex lives that look no different from our culture’s presumed or prescribed norm, to having no sex to speak of. Ace folks might desire sex, or partnership, or romance, or a combination of these, or they might not. All valid. For some deep dives on asexuality, I highly recommend Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex, and A Quick & Easy Guide to Asexuality.

Here’s an example of some of the above terms. Let’s talk about Maria. Maria was assigned female at birth and has a vulva, so she is of the “female anatomical sex.” She was raised in a traditional Mexican-American family, being the child of first-generation immigrants. In Maria’s specific familial culture, women perform femininity traditionally by wearing dresses, having long hair, wearing makeup, and assuming a role in the family where it is prescribed that they are emotionally caring and nurturing, cook, do housework and chores and dote upon and care for male family members. Maria wears her hair long, dresses using makeup and culturally feminine clothing, speaks in a high voice, and takes pleasure in acting feminine, and what this means to her is showcasing parts of her body which she takes pride in, acting cute and fun and quirky. We can say that based on this, Maria is practicing a feminine gender expression. However, Maria takes issue with the role prescribed to her in her family. She does not care to dote on men in her family, resents the idea, and finds this prescriptive norm to be troublesome, as she wishes to leave home and pursue studies abroad and become a researcher. Maria questions whether she really identifies as female, because this norm in her family’s culture is so strong, and she does not feel in alignment with this. Maria also wishes to incorporate less-gendered ways of expressing herself into her gender expression because she finds the femme-only presentation to feel stifling. Maria determines that she identifies as gender nonbinary, and this explains her internal gender identity. Because Maria faces some non-concordance in her gender identity and expression, she may feel feelings of gender dysphoria. Maria feels attraction toward folks of various genders and expressions, and so she describes her sexual orientation as bisexual. Though she’s dated folks of all genders in the past and feels attraction toward them, she might identify her sexual attraction as bisexual, queer, or pansexual. Maria wishes to only date women for the long-term and feels deep romantic connection to them, in a way that she might not feel for folks of other presentations, so she might describe her romantic attraction as gay, lesbian, or queer.

The above example might help to understand the differences in the terminology being used. However, it is still potentially problematic in ways I will explore, as it places her in various boxes, or might not be entirely descriptive of her experience, which is apt to change. Here we come up against a problem of essentialism, which I will expand upon a bit below.

But first — a few more terms, briefly described.

Transgender or the shortened term Trans refers to a person whose gender identity or expression or both might deviate from their anatomical sex or sex assigned at birth. This can be a broad umbrella and I’ll describe some more below.

A note — previously folks used terms like “transsexual” or “tranny” to refer to folks. These terms are now considered outdated and in some cases can be used as hate speech. Do not use these terms. Generally the go-to term now is “trans.” If in doubt, ask.

Also — “transgender” is an adjective, not a noun. It’s more proper to say, “Wow, I just went on a date with a really cool transgender person,” NOT “oh yeah he’s one o’ them transgenders.” A trans person is a trans person. NOT ” a transgender.”

Cisgender (or cis) refers to folks who were assigned a sex at birth, and continue to identify with that gender. I was assigned female at birth and I identify and express as a woman, so I am cisgender.

Trans folks might experience gender dysphoria, a psychiatric diagnosis as of this writing that enables a person to seek gender-affirming care or treatment most often covered by insurance. Gender dysphoria refers broadly to a series of symptoms surrounding a marked incongruence between someone’s gender, body, who they feel to be internally, how they are treated in society, etc. Whether gender dysphoria is a “psychological problem” is hotly contested and leads to stigmatization of folks in the trans and gender-nonconforming community; I’ll say this: the classification of it as a disorder in the DSM-5 allows for folks to seek care and gender-affirming treatment in our current, often hard-to-access medical system. Dysphoria causes folks distress, discomfort, and pain, and can be comorbid with other diagnoses like depression or anxiety. Being trans is hard, and managing dysphoria through various means can help a person who is trans live a better, more healthy, and less stressful existence. Insurance generally covers therapy and medical transitions for folks seeking to treat symptoms of gender dysphoria because there is a broad amount of evidence that these modalities help to treat and reduce symptoms of gender dysphoria.

Nested in the umbrella of transness is the identity known as Nonbinary (or NB, or enby). Our system of classifying sex and also gender is very binary, meaning that there are two main pools to characterize folks into, either being male/female (or masculine/feminine). Folks who do not prescribe to all traditional binary gender norms (that is, 100% masculine or 100% feminine, or corresponding male or female) may identify as nonbinary, meaning that they do not fall into one of the two prescribed buckets of categorizing folks. Some folks might also identify as genderqueer which can be a blanket term for “not entirely cis.”

Additionally, many, many folks don’t fall into the gender binary, such as if they are biologically intersex. Intersex traits, which can include ambiguous genitalia, chromosomes varying from XX or XY, varied primary or secondary sex characteristics, occur in about 1/100 births. Furthermore, folks might not fall into the gender binary in their gender identity or expression, instead existing somewhere in the middle of, or outside of, a spectrum of masculinity-to-femininity. Intersex folks may identify as cis, trans, or nonbinary.

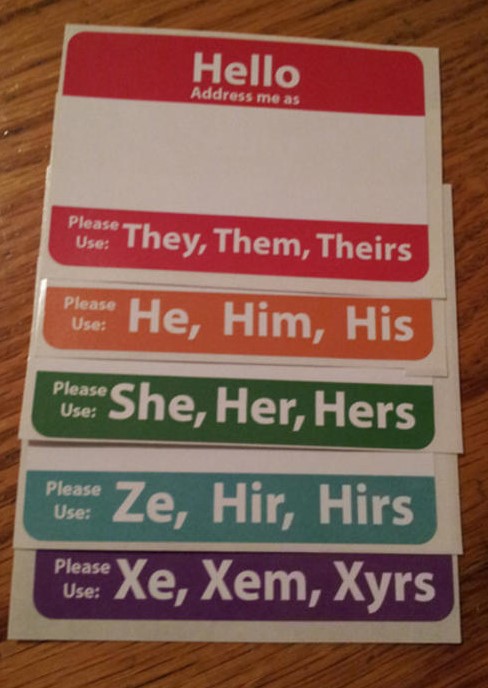

Pronouns are words we use to refer to things, including people. “I” and “me” are pronouns I use to refer to myself. “You” and “that” and “they” are pronouns, as well as “he” and “she.” Pronouns in our language and in many others are gendered, so using a wrong-gender pronoun to refer to someone might cause negative feelings or dysphoria. Therefore, it is important to ask for folks’ pronouns in order to be respectful of them. This is because one cannot discern a person’s pronouns just from looking at them and making assumptions. The language used to be “preferred pronouns,” but now we just say “pronouns,” signifying that they aren’t a preference, they just are. Some folks may use multiple pronouns, such as “she/her and they/them.” That’s fine. Some folks may use what are called neopronouns, which you can learn more about here. If you use the wrong pronouns for someone, the best practice is to correct it and move forward without making a big deal about it and calling attention to it. We get it, folks mess up. Try to do the best you can and don’t belabor the point.

A transition refers to a series of choices a trans person may make to better align their gender expression or physical body with their gender identity or who they know to be inside. Trans folks may choose to take a variety of actions or no action at all when figuring out their gender identity, including but not limited to changing their pronouns, name, clothing, and hairstyle (these actions known as part of a social transition). For many but not all trans people, transitioning will include some amount of physical or medical transition. This can include seeking affirming mental and physical healthcare, Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), and undergoing surgery, or any other means of adapting to more authentically express themselves. Physically or medically transitioning is not a prerequisite or requirement for being trans. A trans person may or may not choose to transition physically or medically for any myriad of reasons and they are still valid. Transitioning in any way, permanently or not, medically, socially, or otherwise, may help to alleviate symptoms of gender dysphoria. Generally, folks who transition report greater happiness and satisfaction; the risk of someone regretting transitioning, and deciding to detransition, is low.

Folks often feel positive effects from expressing themselves as the gender they identify with. This is known as gender euphoria.

Sometimes folks transition toward a desired end goal of presenting as more masculine or more feminine. Generally these folks might refer to themselves as transmasculine (or transmasc) or transfeminine (or transfem) to give a bit more description of where they’re headed, although this terminology is less common.

Folks might say AMAB or AFAB, which refers to the sex assigned at birth (assigned male at birth vs assigned female at birth), this helps to give folks, particularly medical practitioners, information on where the person in question might be coming from biologically without belaboring the point or causing more feelings of dysphoria.

Some folks in the trans community discuss “passing,” which is a term meaning that they can generally not be distinguished from their cis counterparts. Passing is generally regarded as a privilege, and a means of safety in areas hostile to trans folks, and discussions on passing can also be used in a hurtful manner. Folks who pass and don’t disclose their trans identity may be known as “stealth.” A trans person does not have to disclose private information about their medical history, biology, dysphoria, or transition to another person; being stealth is a valid way to be should a person choose to do so free of coercion or pressure. Another person discussing or disclosing someone’s information in this way without their consent is known as “outing” and is generally frowned upon, as giving folks say in their life and who to come out to is preferred.

Means of physical medical transition include Hormone Replacement Therapy or HRT (a person taking hormones to better align their biology with their desired gender identity or expression), Top Surgery (generally a reduction, mastectomy, or breast implants, depending), Bottom Surgery, Lower Surgery, or Gender-Confirmation Surgery (surgery to adapt internal or external genitalia), and a few various others that you can research should you choose to do so. Again, trans folks are valid without undergoing surgery or beginning hormones. Folks may choose to not have surgery or take hormones, and change their mind at a later date. Some take hormones only for a time. Some get one surgery but not another. That’s all quite normal.

Drag and crossdressing (now known less controversially as just dressing) are a performance of gender and an expression of gender that may not be tied to a person’s gender identity. They are activities that can be practiced by someone regardless of gender, sexuality, or sexual orentiation. Many practice drag and dressing to have fun, perform, and cast light on the ridiculousness that gender really is in a culture that practices essentialism. Now that we’re on that topic…

Deconstructing Cultural Contexts

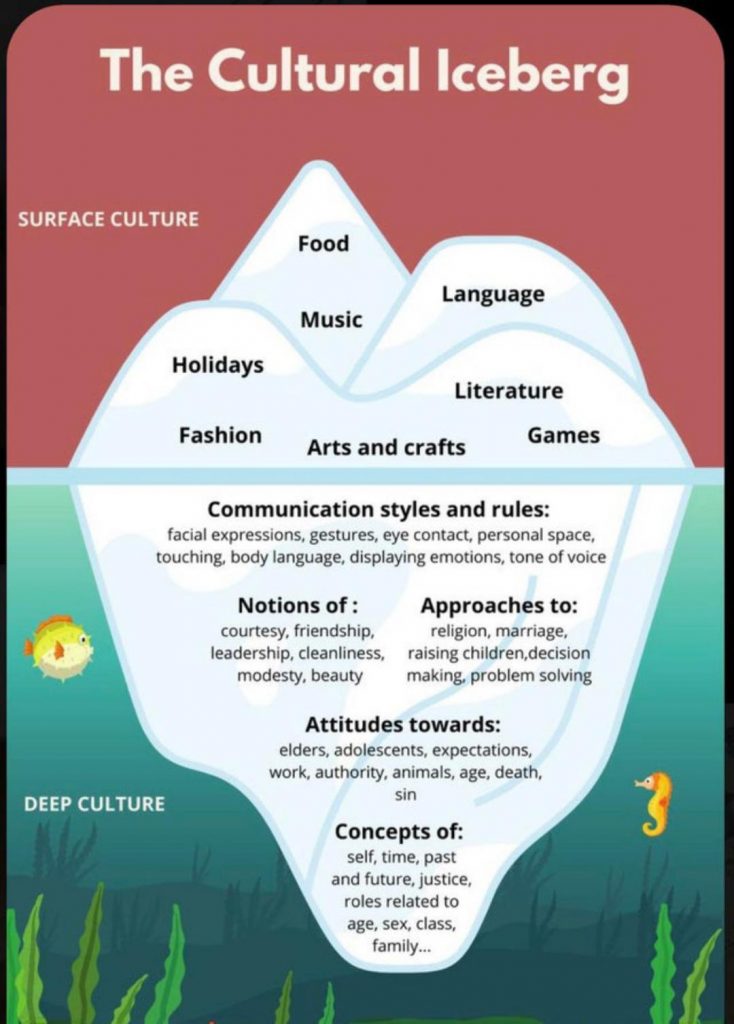

Gender, sexual orientation, and sexuality are best viewed in context. Meaning that the words we use to describe these things, and even the very fabric of how we regard them, are nested into our culture, upbringing, time period, and so on. There’s no objective answer to any of this; it’s based entirely on our subjective view of the world which is informed by the way we were raised and the scripts we were taught. I identify closely with the framework known as post-structuralism which is a lens through which to view these topics in context, and you can read more about this in the great book, Queer: A Graphic History.

This is in contrast to Essentialism or biological essentialism, which is a term I use here to refer to the cultural tendency to view sexuality and gender as something that is ingrained deeply in our biology and is therefore unchangeable. Essentialist ideas tell us that our identity is fixed, and they follow determinism in that they assume that folks’ gender and sexuality are determined by their physiology (including hormones & genetics). These ideas are of course not so, and are disproven time and time again both in humans and in the various diverse biologies and lives of all sorts of other organisms that inhabit our planet.

This view of sexuality stuff made sense earlier in queer activism, when identity politics were essential to establish queerness as “not a choice” with the mantra of “born this way.” This was necessary to contrast folks’ non-cishet lives against the stigma presented by dominant groups at the time which claimed queerness was an aberration, a choice, or a lifestyle. Activists had to claim they were “born this way” in order to solidify messaging against sexuality, queerness, or gender being simply a “choice” that they could be coerced out of, particularly in the time of panic and misinformation around HIV/AIDS. This put individualistic representations of sexuality and gender as front and center, which led to the “coming out” model that still persists today.

Post-structuralists can view this way of being as an important step in equality and equal rights, for many, many reasons. Scholars such as Michel Foucault and Judith Butler put forth ideas that there is no “universal truth” relating to gender and sexuality, and that our understanding of this is important in context. Queer theory works to deconstruct text, thinking, and activism around these topics and understand intersecting identities, ideas, politics, culture, and time among other things (including living in a capitalist society that survives on telling us we are not enough unless we buy in and also a culture with a heavy emphasis on self-monitoring to adhere to a norm of being a good person). As a fence-sitter, it might feel better to understand gender and sexuality as something that is constructed through all the aforementioned cultural constructs, and performed — something that we do or express rather than something that is an essential part of who we are, because it is so changeable in the seasons of our lives. It is important to understand this in context again, as various systems of power and control overlaying us also dictate scripts that influence how we feel allowed to feel, identify, perform, etc.

Furthermore, when you add gender and its changeability into the mix, our system for codifying and explaining sexuality and sexual orientation kind of breaks down.

Take Bo. Bo was assigned female at birth, but it never quite fit. As a teen Bo realized they liked women, as in they like liked women (hanging cutouts of Jessie and — begrudgingly, James — from Pokemon on their wall, anyone?), and after much struggle, figured they might as well label themself with the (at the time feared) term of lesbian. Still, they felt uncomfortable with this identity, and still felt ousted from traditionally feminine spaces or activities, preferring instead to partake in activities as a tomboy or “one of the guys,” and feeling great discomfort with their body, choosing instead to wear thick hoodies and slouch to the reprieve of invisibility, at times envying women who felt comfortable enough, they figured, to be “lipstick lesbians,” who are traditionally more femme-presenting. In their late twenties, after a few prominent figures came out as trans, and this was more the subject of discussion, Bo learned about transgender and nonbinary identities, and did a lot of research and self discovery before coming out as a trans man. Bo, in a relationship with a woman, now no longer considers themself a lesbian, as they aren’t a woman with attraction to women. Bo mused, would he now consider himself a straight man? Is that the label that works?

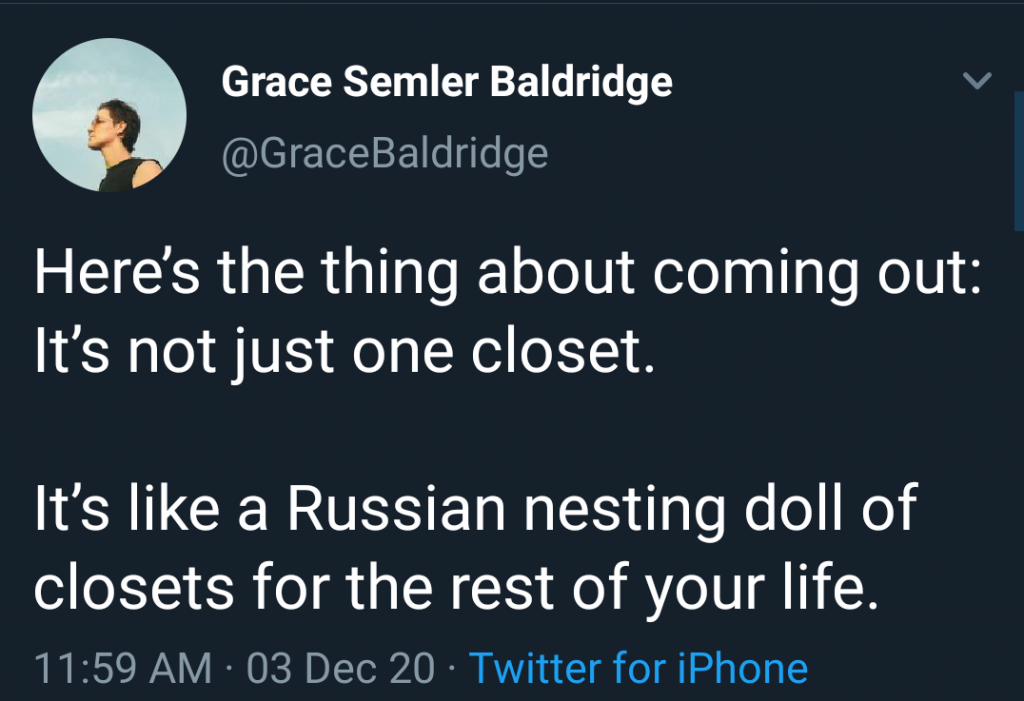

Notice all the labels in the paragraph above? Sometimes it feels like you need a hard copy of the urban dictionary to keep up with labels for stuff (in any regard, whether sexuality, a specific fandom, the kink community, golfing, or heavens forbid professional wrestling, babyface). Labels are a great way to better understand oneself and to learn where to find community (saying hey, I’m a monsterfucker explains it better than hemming and hawing, and then we can find the subreddit much easier), but are also hard because they too rub up against hard-learned principles of Essentialism that again, while once necessary, no longer really cut the bill. That is, labels can and do change, whether with time, preference, self-discovery, culture, or something else, and this is all well and good, normal, healthy, however else I can say it — worth affirming. And yet, in a culture that demonizes “flip-flopping” (I first heard of this term in some old political JibJab video about the 2004 election, remember those days?!), discovering and exploring new means of identity can feel like iron bars, or at least, a new sack of potatoes (and not the baby kind!) added to the queer backpack already cutting into our shoulders. Discovering new interests, ways of understanding oneself and interacting with the world, or private goings-on, then becomes a thing that one must come out about, almost “come clean” about, in a sense: if labels are essential, and we identify so strongly with something that we are that thing, or it’s a deep part of our identity, we must do something, right? It’s this societal and cultural script around Essentialism and identities and coming out and labeling oneself, not to mention labeling others, that can feel like quite a weight to bear. It is understandable to view this process with some trepidation, or rejection altogether (it’s also valid to jive with this process and find little to no issue with it too, by the way — I’m just exploring some troubling scripts that might come up). Tl;dr: Labels have benefits, and Essentialism was important, but then we run into all kinds of stressful problems in the wake of inflexible societal and cultural scripts.

Back to that example, too, yes, adding gender stuff in often fucks up the whole Essentialism paradigm of labelling sexuality in our culture. For some fucking reason, we describe our sexual orientation as something static (“I was born this way,” explained above), but moreover we explain sexual orientation using our gender and then the gender of our preferred partner. If you see me, and I present femme, and I say I’m gay, you can guess I like women. If you don’t know my gender, and In say I’m gay, you can guess I like folks the same gender as me, whatever that is. If we’re on a message board and I say I’m a lesbian, you can make a pretty assured guess that I’m a woman who loves women. If I come out as male later, then my label becomes… straight? It feels bizarre, but that’s not because my situation is, or I’m misleading you or whatever; it’s because the labels we use to say “I’m attracted to XYZ!” for some reason take our gender into account, which, when you break it down, makes little sense. But, if I say I’m bisexual or pansexual or queer, my gender doesn’t matter anymore, and you can presume I like whatever — folks of any gender, let’s say, and if you don’t know me and I say this, you get also fuckall about my gender identity. This is a major reason why many are choosing to reclaim “queer” as a label, not just to reappropriate it in a positive light, but also because it’s helpful because it can tell you nothing about my gender or preferences other than “not straight” or “not cis/het.”

There’s some schools of thought who say we can describe sexuality as just “I’m attracted to these genitals,” like, I’m attracted to vulvas. But this still gets fucked up by gender not being a binary (and rightfully so). Some folks describe sexual attraction, then, as “I’m attracted to masculinity,” which might fit a little better — one can like male-ness in representation, whether that’s coming from a traditional cis dude, a dude who’s trans, a masculine nonbinary person, a woman who’s more butch, whatever. But still, it feels like these terms are trying to stretch a strip of Saran wrap over a grandma-level lasagna and it’s not quite fitting. So we can’t put it in the fridge yet because we want to delicately love and treasure it and keep it well for as long as possible, and that requires it to be wrapped well. Basically, the above describes issues in our nomenclature for gender and sexuality, and these issues exist and have not yet been resolved, at least in a way that general society adopts. So people fuck up a bunch in their understanding, conceptualization, and labelling of this stuff, which also hurts folks in the LGBT community who face misunderstanding, judgement, and bias, among other outcomes and disparities.

In the example, Bo was assuredly a lesbian as a teen and to question this or invalidate it would be highly inappropriate and potentially abusive. Bo is allowed to question and relabel it, however, and should face no penalty in doing so; instead those who are privileged to learn about Bo’s new way of understanding themselves and the way they fuck with the world around them (transmasc in this example, baby) are prescribed the affirming script of believing them and following their lead regarding pronouns and they way they’d like to receive love, care, and support. Unfortunately, there are prescriptive norms in our culture based on bigotry, hatred, misinformation and misunderstanding, biological essentialism, some religions, you name it, that can make it hard for folks to do so as readily.

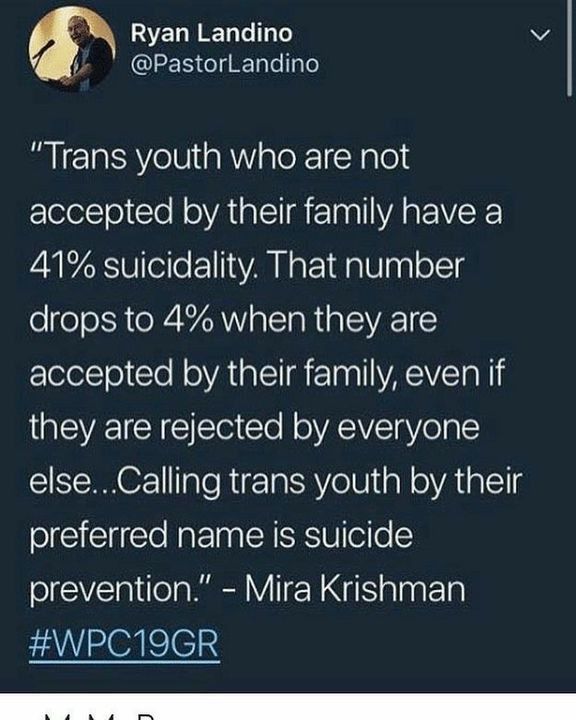

As aforementioned, presenting pushback on a person’s coming out, identity, labels, or preferences is problematic for their health and wellbeing. I understand the worry about stuff being “just a phase,” or folks who might be “transtrending,” which is a cover-all term for folks who might not feel gender dysphoria and be aligning themselves with the trans community for acceptance or assurance among other positive outcomes (this topic is discussed in more detail across the web and I don’t presume to do it justice in this short piece, please check out this article or Contrapoints’ video essay on the matter). It’s reasonable to feel worry and care on behalf of a loved one and these feelings are often rooted in love rather than an overt desire for oppression.

That being said, the MO, at least at the time of this writing, is to affirm and support a person who is exploring their gender and sexuality, and to believe folks when they say how they feel, what they like, how they’d like to be addressed, etc. If one has questions, much research can be done now as there are a myriad of resources for one’s own learning so as to not place the entire burden of education on the shoulders of the queer person in their life. Look for varied sources. Deconstruct the lessons you learned about gender and sexuality from our culture and understand your feelings in context.

How to Affirm: Best practices for supporting a loved one who comes out as trans

As aforementioned, make space for them to express themselves appropriately. Practice active listening skills.

Get to know your own reactions, biases, and feelings relating to the matter. Understand that any internal resistance you might feel is a result of the cultural upbringing we had to endure, and educate yourself to this end. Allow yourself space to feel all sorts of feelings and make a note that you will practice self care later.

Listen, affirm, ask caring and affirming questions, validate any feelings they might have.

Offer support and resources if possible.

Get to know their new pronouns and name if applicable. Use them and practice them as much as possible when the person is around and when they are not.

Do research in ways that you can to understand terminology and such so you can be better prepared for future conversations where you can “get into it” more without placing responsibility on them to educate you on all things.

Understand they might not have all the answers just yet, and make space for continued growth and development on their end.

If they desire you to not “out” them just yet, respect those wishes.

Normalize introducing yourself using pronouns, even if you’re cis.

What if I mess up the pronouns? What if I mess up the name?

Using wrong pronouns is known as misgendering, and referring to someone by using their old name if they’ve chosen a new one is called deadnaming. Both are considered faux pas of varying degrees when interacting with folks, whether they are present or not.

Generally, best practices are to acknowledge the mistake, correct it, and move on.

“So he went to the bar and — oh! Sorry, I meant she. Anyways, she went to the bar and…”

“I took my daughter to the barber and — I mean son, sorry — took my son to the barber and we got a new haircut which looks great.”

“I got a call from Deborah today — sorry, I meant Atlas, so anyways Atlas called and we talked about their new cat.”

In the same way, correcting someone else on a mistake, gently, briefly is appropriate.

“Atlas uses they/them pronouns. Please continue.”

It’s recommended to not make a big deal of this, overly apologize, or bemoan your personal difficulties in using the correct name or pronouns for someone. Doing so can cause a scene, be awkward, or refocus attention on the wrongdoing, which can feel at best tactless and at worst harmful for the person in question.

Examples of no-no’s —

“Oh gosh, they/them pronouns are just so hard to remember, you can’t always get on my case for making just a simple mistake.”

“Your name has been Elmira for seventeen years and I’m going to continue to refer to you as such in mixed company, after all it’s fine because you aren’t there, right?”

Using someone’s correct pronouns and name even when they are not present is important to continue to make it a habit of naming and gendering them correctly when they are there. Furthermore, it’s a sign of respect that you view them always as the right gender etc., not just putting on an act when they’re around. It can be difficult to pick up but becomes more readily accessible with continued practice.

Don’t ask what people’s genitals are. Just don’t.

What if a person I love experiences violence or discrimination because of their gender or sexuality?

Unfortunately folks in the queer community disproportionately face discrimination and violence, hard times, dysphoria, and related stuff that makes life hard. Because of disparities in our culture relating to opportunities and support for folks in marginalized or minority communities, finding help and support can sometimes feel challenging. Some great resources to get started on where to look in helping to support a loved one might be the Trans lifeline, a peer support space run by trans people. It might also be helpful to find a therapist who understands gender identity, and psychologytoday.com is a great resource for this because you can filter by practitioners who specialize in affirming gender identity. The ACLU also has a bunch of helpful resources. Remember that you offer your loved ones your love, support, presence, and attention, and that in and of itself can be healing.

What sorts of things can I do to learn more about this stuff? How can I help?

Fortunately, we exist in a time where there’s a myriad of content that one can educate themselves with. I have some related resources below, but it barely even scratches the surface, to be honest.

Part of learning more about this is scholarly, and scientific, and educational, and all that, which you can cover with resources. And another part is very personal, where one “does the work™” to understand one’s own reactions and inherent biases, and then deconstructs these scripts, feelings, messages, impulses, etc. in order to better understand their influences and origins. After putting these feelings in context, one may decide how to proceed: do we throw the feeling or thought in the trash or do we modify and keep it? This is oversimplified of course, but hopefully you get the gist. A great place to practice this, come to terms with stuff, and work through it is in therapy. Having an unbiased and educated listener is extremely helpful. Individual therapy is great for this, and groups also exist for parents of LGBT youth, if that’s where you’re at.

Related Resources

National Geographic’s Gender Revolution Guide

https://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender

The Transgender Training Institute

https://www.aclu.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/transgender-rights/transgender-people-and-discrimination

Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center

Dr. Roizin @ Allentown Women’s Clinic

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/transgender

https://www.reddit.com/r/traaaaaaannnnnnnnnns/

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex

A Quick & Easy Guide to Asexuality

The Savvy Ally: A Guide for Becoming a Skilled LGBTQ+ Advocate

Parenting Your LGBTQ+ Teen: A Guide to Supporting, Empowering, and Connecting with Your Child

1 Reply to “Trans 101”

Comments are closed.